Coercion and Freedom in the Fate of the Individual

1991

Studying medicine and later specializing in psychiatry at university led Buxbaum to explore the history of the field.

His work Coercion and Freedom in the Fate of the Individual is inspired by the theoretical writings of Cesare Lombroso (1835–1909), who examined the physiognomy of criminals and proposed classifying them into psychological types based on appearance. This line of inquiry was further developed by Hungarian psychiatrist, psychoanalyst, and psychopathologist Leopold Szondi (1893–1986), a student of Sigmund Freud. In 1956, Szondi formulated the theory of Genotropism, which recognized the deterministic influence of genetics and family heritage, while also emphasizing human agency—the ability to make conscious choices and transcend inherited tendencies.

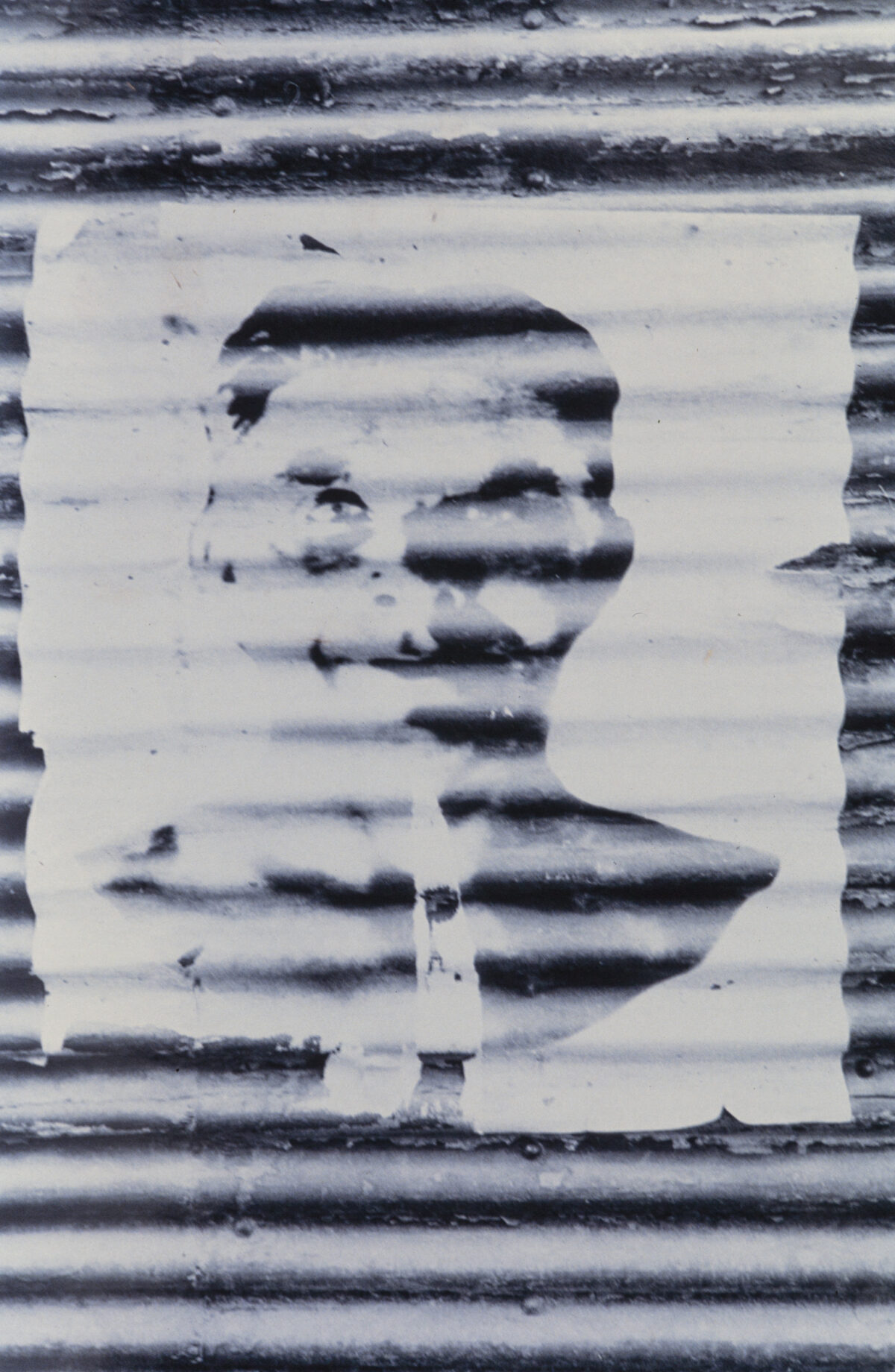

Szondi examined psychiatric patients and photographed their faces. In his book Coercion and Freedom in the Fate of the Individual, he proposed a projective personality test using these photographs. Participants were shown portraits of individuals with psychiatric diagnoses—schizophrenics, manics, depressives, epileptics and homosexuals as homosexuality was then still categorized as mental illness. Participants were then asked to divide the 48 cards into two groups: “sympathetic” and “unsympathetic.” The “sympathetic” group was thought to reflect the subject’s own psyche, offering insights into their personality structure. The test remained in use until the 1990s, although its assumptions were ultimately refuted both theoretically and empirically.

Buxbaum was intrigued both by the expressions in these outdated test photographs and by the medical misuse of the portrait—arguably the most “sacred” of artistic formats. The face, long considered the mirror of the soul, had been used in physiognomy and later in racial theories to judge individuals and determine their fates.

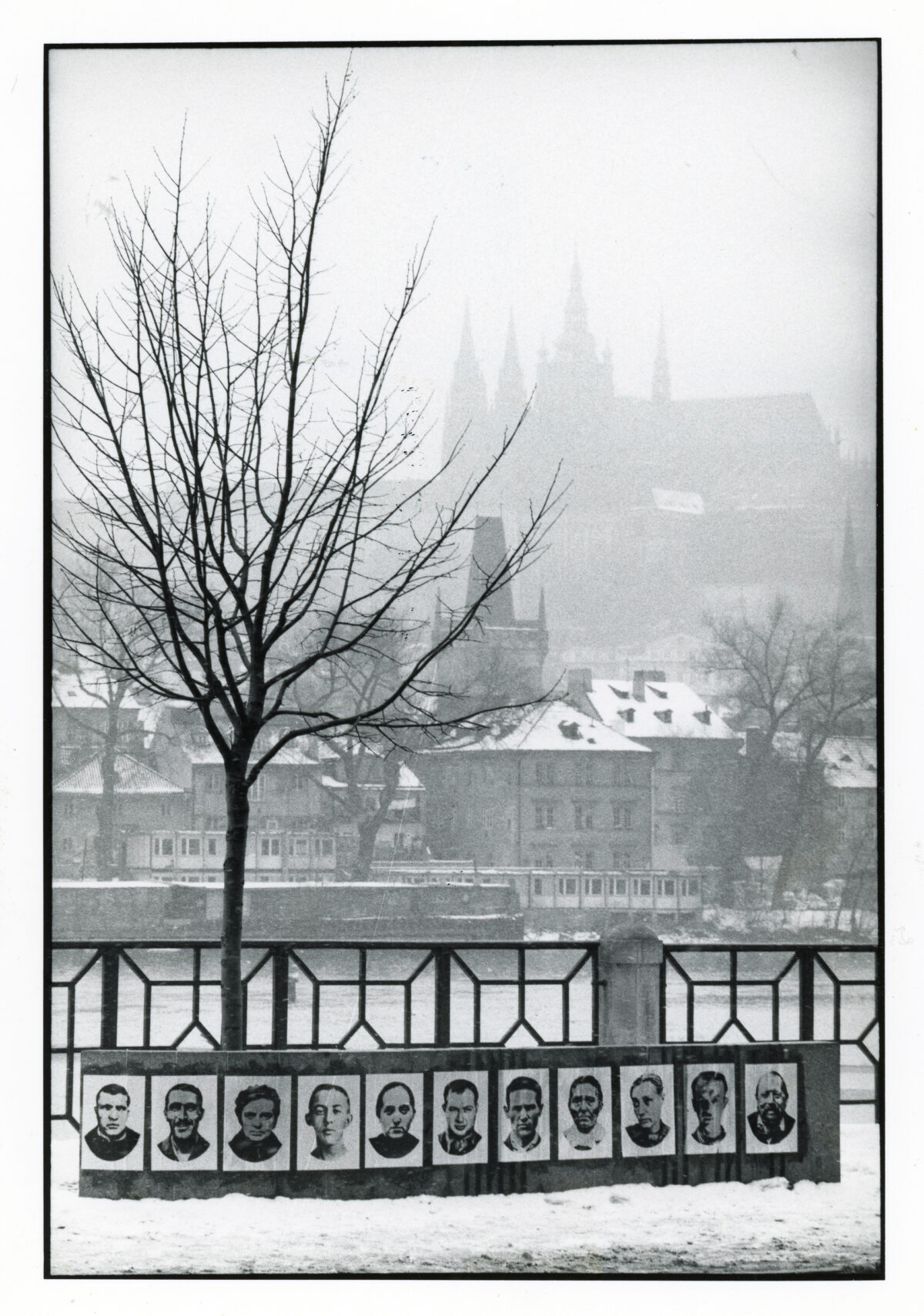

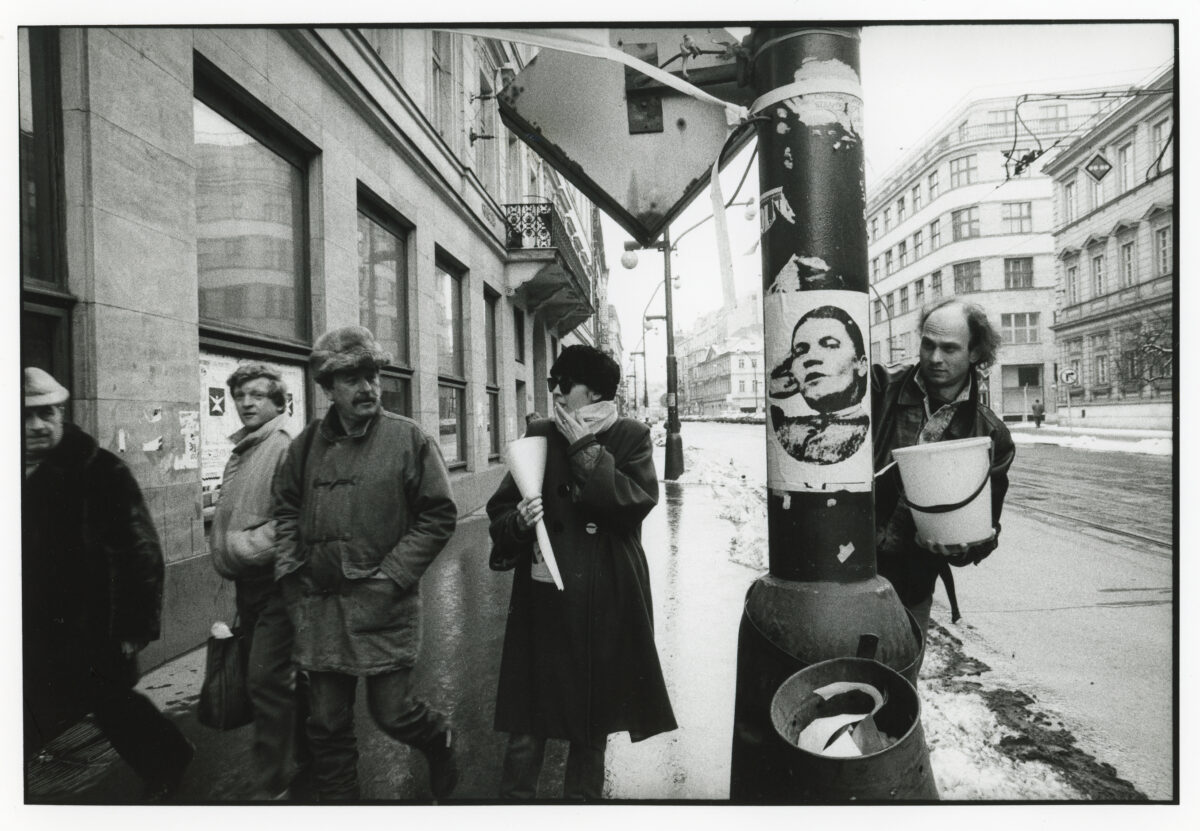

In 1990, Buxbaum selected 16 faces from the Szondi archive and printed them as posters, calling it “my own Lombroso test – my psychological profile,” which he incorporated into installations. As part of an exhibition at the gallery U Řečických, he launched a large-scale poster campaign, plastering over 3,000 posters across the city. In the still largely ad-free public spaces of post–Berlin Wall Prague, these mysterious posters—with no text or explanation—sparked media speculation, including rumors that they depicted Moravian politicians. The true origin was revealed only when someone from the Szondi Institute recognized the images.

Buxbaum was subsequently labeled a “psychological terrorist.” His intervention effectively ended any further use of the Szondi test, since the faces were now widely recognizable. The project became the first artistic poster campaign in Prague.

Studying medicine and later specializing in psychiatry at university led Buxbaum to explore the history of the field.

His work Coercion and Freedom in the Fate of the Individual is inspired by the theoretical writings of Cesare Lombroso (1835–1909), who examined the physiognomy of criminals and proposed classifying them into psychological types based on appearance. This line of inquiry was further developed by Hungarian psychiatrist, psychoanalyst, and psychopathologist Leopold Szondi (1893–1986), a student of Sigmund Freud. In 1956, Szondi formulated the theory of Genotropism, which recognized the deterministic influence of genetics and family heritage, while also emphasizing human agency—the ability to make conscious choices and transcend inherited tendencies.

Szondi examined psychiatric patients and photographed their faces. In his book Coercion and Freedom in the Fate of the Individual, he proposed a projective personality test using these photographs. Participants were shown portraits of individuals with psychiatric diagnoses—schizophrenics, manics, depressives, epileptics and homosexuals as homosexuality was then still categorized as mental illness. Participants were then asked to divide the 48 cards into two groups: “sympathetic” and “unsympathetic.” The “sympathetic” group was thought to reflect the subject’s own psyche, offering insights into their personality structure. The test remained in use until the 1990s, although its assumptions were ultimately refuted both theoretically and empirically.

Buxbaum was intrigued both by the expressions in these outdated test photographs and by the medical misuse of the portrait—arguably the most “sacred” of artistic formats. The face, long considered the mirror of the soul, had been used in physiognomy and later in racial theories to judge individuals and determine their fates.

In 1990, Buxbaum selected 16 faces from the Szondi archive and printed them as posters, calling it “my own Lombroso test – my psychological profile,” which he incorporated into installations. As part of an exhibition at the gallery U Řečických, he launched a large-scale poster campaign, plastering over 3,000 posters across the city. In the still largely ad-free public spaces of post–Berlin Wall Prague, these mysterious posters—with no text or explanation—sparked media speculation, including rumors that they depicted Moravian politicians. The true origin was revealed only when someone from the Szondi Institute recognized the images.

Buxbaum was subsequently labeled a “psychological terrorist.” His intervention effectively ended any further use of the Szondi test, since the faces were now widely recognizable. The project became the first artistic poster campaign in Prague.