Doors to heaven

2012

“As a boy, I always spent my summer holidays with my grandmother in Kyjov. The children of the small town met outside to play. A meeting place for boys was the asphalt pitch in front of the garages of a large housing estate. Here we played football until the mothers called the children’s names out of the window when the food was ready. The garage door was declared the target of the ball. If you hit it, the ball thundered against the metal of the garage door and loudly announced the goal. Even today, ten-year-old boys thunder their footballs against the same garage doors and, like the bell from the church tower, here at the garage every goal announces the flow of time. The Doors to Heaven stand between eternity and transience. In the Czechoslovakia of my childhood, the automobile was a symbol of success and prosperity. Even more than in the other countries of the Eastern Bloc, the men of the car nation of Eastern Europe were skilled car mechanics. The Škodas, Ladas, Tatras and Wartburgs were looked after and cared for, they were dismantled, oiled, serviced and, if necessary, repaired by hand. The garages were well-equipped workshops. Tools of all kinds hung on the walls. It smelled of lubricating oil, beer and sweat. Faded calendar pictures of busty blondes stuck to the walls and toolboxes and awakened early longings in the adolescent. The men drank beer and Slivovice and talked about pistons, gears and horsepower. A perfect world for a boy. In socialist times, going to the garage replaced going to church on Sundays. The garage was the home of the car, but also a place of escape and freedom. Before the celebratory family outing, the car was rolled out of the garage, washed and spruced up. Cleaning the car had almost cult dimensions. Women also helped with this ritual. Our neighbor Miroslav Tichy also liked to come here and take photos of the women bending down or getting out of their cars. But more about that in other books. Everything was beautiful in front of the garages on Sunday – the women and the cars were shining and the men were wearing white, freshly ironed shirts. The stories of my fathers and grandfathers are intertwined in my memories with the stories of their cars. As a boy, I admired the men and their cars. My paternal grandfather was called Herman and owned a car called “Polularka.” It was old and had to be started by hand. Every trip began with “starting the Popularka.” Grandma and I were ready for the trip and watched Grandfather with excitement. First, Grandfather rolled up his sleeves and opened the hood. With a tense face, he turned and screwed the levers and adjusting screws of the carburetor, checked the spark plugs, the cables and the fuel tap. Then grandfather knelt down in front of Popularka and stuck a crank into a hole in the engine. He said to Popularka, telling her to be a good girl and start the engine properly this time. Then grandfather cranked the engine hard and swore, as Popularka would not start for a long time. Although his curses were hardly understandable because grandfather always had a cigarette in the corner of his mouth, grandmother scolded him, telling him not to talk so rudely in front of the child. When Popularka finally started, grandfather had to quickly get into the car, accelerate and fiddle with various levers to give Popularka the right mixture of petrol and air. Only when the engine roared loudly had we won and grandfather’s face beamed with a broad smile. Now grandmother sat in the passenger seat and accelerated with her left foot, while grandfather worked the crank and closed the bonnet. The trip could begin. In summer we usually drove to the pond in Milotice. It was always exciting to see whether Popularka would manage the hill that separated us from our destination or whether she would come to a standstill with the engine smoking. When the engine started to sputter, Popularka naturally had to be talked to again or even scolded.

Shortly after my birth, my father and mother took me from Prague to Kyjov in a laundry basket on the back seat of an Opel Olympia to show me to my father’s family. The Opel Olympia belonged to my mother’s father, Vladimir, and was built in 1952, just four years older than me. Grandfather Vladimir was the son of a simple railway employee in Karlštejn. He came from a poor background, but was hardworking and skilled. After an apprenticeship as a blacksmith, he became a toolmaker in the Kolben Danek machine factory in Prague and is said to have had two hundred workers under him in the 1920s. His innate skill and energy in the workshop were legendary. I remember the stories of his heroic deeds. When he once again dared to make the long journey from Karlštejn near Prague to Kyjov in the Moravian province to visit his family, the engine’s piston burst just before Kyjov. The following day, grandfather paid a visit to the comrades at the screw factory in Kyjov, where he cast a new piston from steel based on the damaged original. The next day, the repaired car with the brand new, hand-made piston drove flawlessly 300 km back from Kyjov to Prague. That’s how skilled my grandfather Vladimir was. The men who shaped my original families couldn’t have been more different. On my father’s side, there were farmers’ sons who worked their way up to become entrepreneurs, Jewish ancestors, merchants, owners of a soda factory, or dentists like my grandfather Rudek, who wrote plays and recorded records on his musical saw before he was killed in Majdanek in the summer of 1942. And then there was the workshop master Vladimir. On my mother’s side, there were stories of noblemen and horse dealers, railway workers and hard-working workers. Cars and horses were the companions of all my ancestors. On my mother’s side, the Pejsa family had been involved in the horse trade for generations. Great-grandfather Josef Kopečný from Kyjov had made a rapid rise from farmer’s son to saddler and strap maker in Kyjov. At the end of the First World War and thanks to the Spanish flu, he had set up the “Pieta” funeral home in addition to the saddlery. When he then married a trained artificial flower maker who brought the necessary aesthetic know-how in decorating corpses, horses and coffins to the business, the family was able to buy one of the first cars in Kyjov in the 1920s. What a rise in Svatoborská. Horses have been decisive for the development of our cultures for tens of thousands of years. The wheel, the plough and wars were not fought by people, but by people and horses. The age of horses is hardly imaginable in the age of horsepower and fossil fuels. Memory is so short, remembering so difficult. In thousands of years, the horse transformed Eurasia. The wheel, the plow, the saddle, the stirrups, and the war on horseback changed the world. It was only a hundred or two hundred years ago that horses were replaced by machines – cars, tanks, airplanes, submarines. And garages replaced horse stables. When grandfather Vladimir was already ninety, his 1952 Opel Olympia was standing on wooden trestles in the garden in Karlštejn. “I’m on my last legs,” he would say, gently stroking the hood of the equally disabled car. It was clear that this car was dear to his heart and that he shared his fate. I bought the vehicle from him and decided to restore it. The goal was to ceremoniously drive through Karlštejn with my grandfather and celebrate a victory over time and decay. Grandfather died. My mother died. And the car is still not finished. The window seals are still missing and I still want to continue the heroic deeds of my ancestors in the field of automobiles. But I haven’t given up yet.

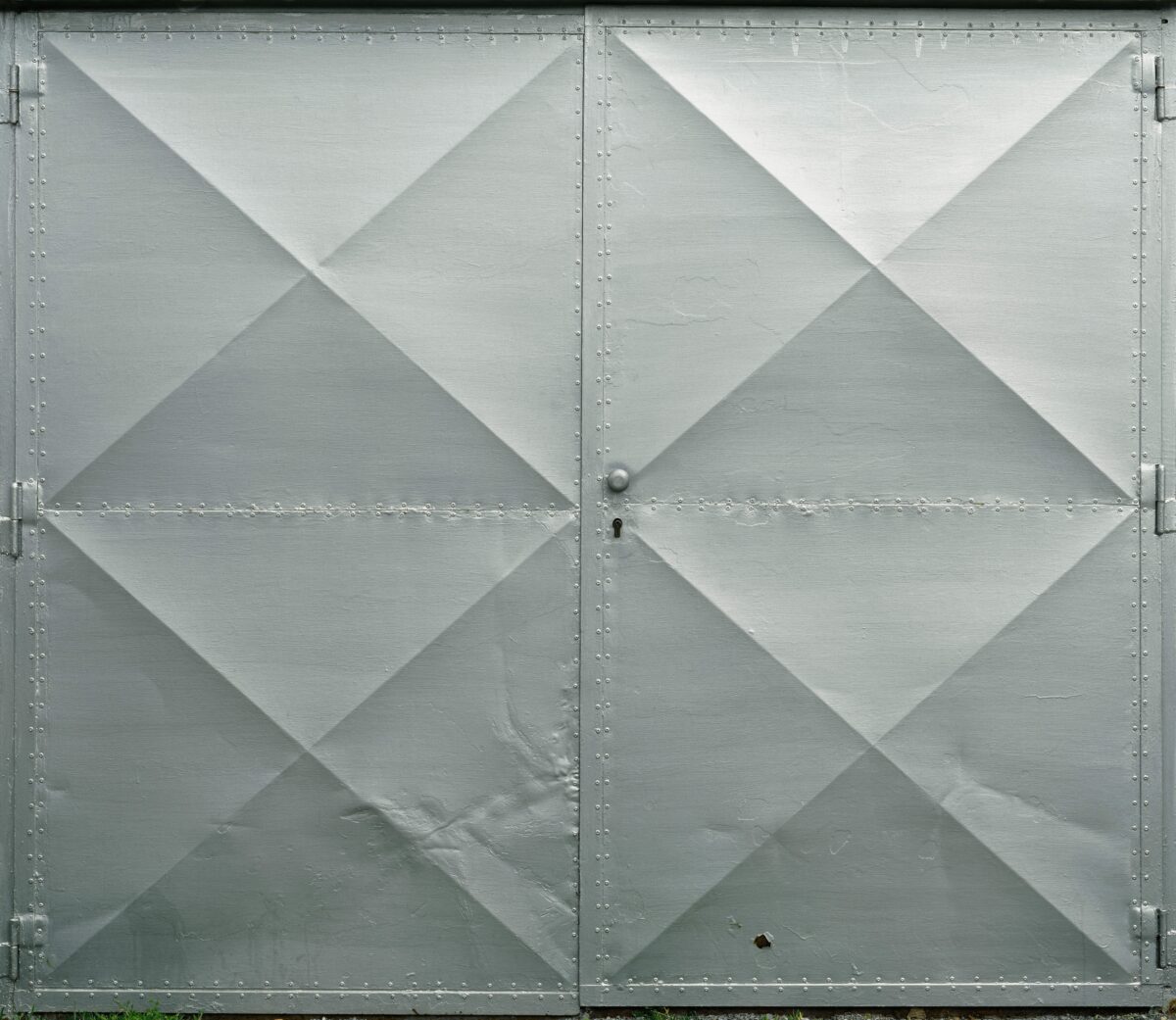

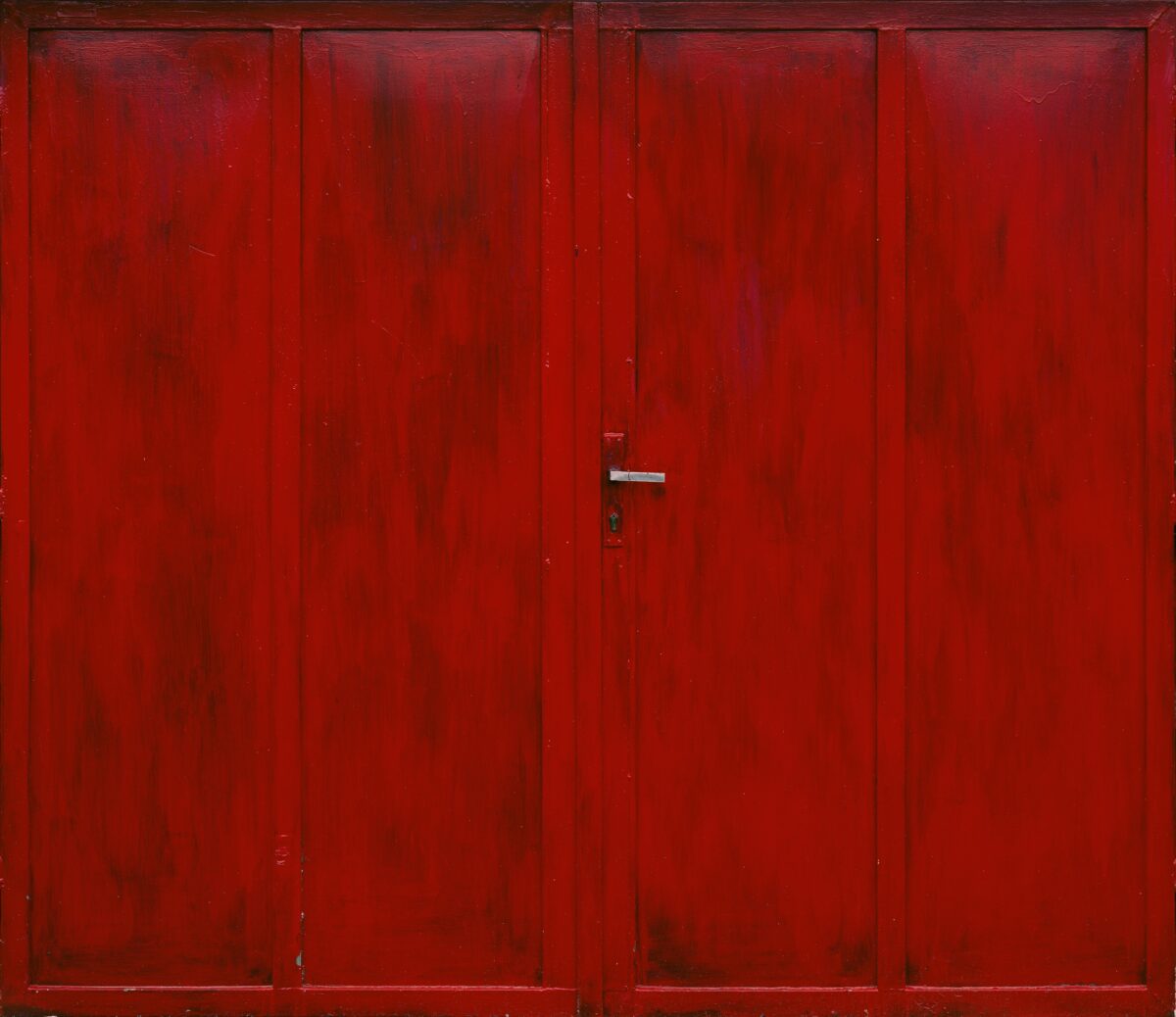

Unlike in the Swiss cities that I got to know after emigrating in 1968, garages in Czechoslovakia were not integrated into the residential buildings. The housing estates in the Eastern Bloc were built without garages. Firstly, the prefabricated buildings of the 1950s were much cheaper without the expensive underground garages. Secondly, the car was not an everyday vehicle – it was only needed on Sundays. The socialist workers’ housing estates were built on the outskirts of the city, where there was enough cheap building land. So the garages were built some distance away from the housing estates. The garages were built in rows like honeycombs and were all the same: a body made of three concrete slabs and a flat roof. So small cities for cars were built next to the housing estates for the workers. Man and machine were treated equally. Socialist urbanism reorganized the villages. The prefabricated buildings for the people, the garages for the cars and the cemeteries for the dead. The front of a garage was closed off by a gate. Like all other components of the garage, the gate was also prefabricated. The garages and therefore the gates were all the same size. First, a steel frame was covered with wooden planks. Over time, different “models” were used in which the steel frame was fitted with sheet metal plates. To ensure the stability of the garage door leaves, the frame of each leaf had to be reinforced. This was done using cross-shaped struts. Four sheet metal parts were then usually welded onto these “crosses”. The gate was now ready to be installed. The gate to the man’s paradise, however, had to be protected from earthly things. The weather, wind and temperature fluctuations cause iron to rust. As a preventative measure, the man has to paint his garage door. First, the old paint residue is removed with a gas burner and rusty metal parts are sanded off. A primer will be the painter’s first important job. When the primer is dry, it usually has to be sanded again. Then the man has to show his colors. What color should the garage door be? Red? Green? The same color as the neighbor? The same color as last year? A color that no one else has? Or do you just take a leftover that you find in the garage? Color does not represent emotion, here color is a concept. The painter is not doing it for fun! He does not want to express feelings. No room for expression. Not De Kooning or Arnulf Rainer, here the inspiration is Ives Klein and Günther Förg. Gate after gate, monochrome after monochrome, limb after limb, the rows tightly closed, high and still higher! Since the “New Wild” we have been looking for the immediacy of painterly expression. We wanted to get away from academic painting and towards the naive and the amateur. Many of us drew with our left hand back then. A fellow student at the Munich Academy guided the brush with her anal muscle and impressed Daniel Spörri’s entire class. Güther Förg told me that he had his cleaning lady make certain large-format canvases, giving her small sketches on paper as a template. From Baselitz and Penk to Andy Hope in 1930 and Jonathan Meese, painters sought the unaffected, authentic picture that only a layman, a child or a madman could paint. Or someone who painted his garage door. Private painting work in real social life was not carried out by professional painters. The painter was the man who owned the garage. The garage door was the gate to his paradise – or at least an image of it, a kind of abstract self-portrait. The garage doors are paintings by men who of course did not see themselves as artists. They paint – because they have to paint! The garage doors are amateur paintings. They lack anything artificial, any mannerism, any urge for decoration, expression, ornament. Every door is a painting that makes the painter visible. His stroke, the choice of color, the way he applied the paint, everything gives us an idea of the author. No two gate pictures are the same. A picture by an unknown painter, with no artistic intentions. To paint a large area with as little color as possible in as short a time as possible, well enough to protect the gate from rust for a long time and beautiful enough not to be embarrassed in front of the neighbors.

A grey winter day is ideal for taking pictures in natural light. Together with Ondřej Polák I photographed eighteen garages, which I selected based on painterly criteria. Ondřej Polák is a sought-after museum photographer in Prague, specialising in photographing paintings and exhibitions. I asked Ondřej to treat the garages like paintings. We photographed on Kodak E 100 film (9 x 13 cm positives) and then enlarged them on Kodak Endura photo paper. I had the unique pieces mounted in oak frames. I chose a height of 80 cm as the format, which was half the height of the garages, or about a quarter of the area of the garage door. A quadrangle is a special scale – too big for a model and too small for a replica of reality.”

- RB (December 2024)

“As a boy, I always spent my summer holidays with my grandmother in Kyjov. The children of the small town met outside to play. A meeting place for boys was the asphalt pitch in front of the garages of a large housing estate. Here we played football until the mothers called the children’s names out of the window when the food was ready. The garage door was declared the target of the ball. If you hit it, the ball thundered against the metal of the garage door and loudly announced the goal. Even today, ten-year-old boys thunder their footballs against the same garage doors and, like the bell from the church tower, here at the garage every goal announces the flow of time. The Doors to Heaven stand between eternity and transience. In the Czechoslovakia of my childhood, the automobile was a symbol of success and prosperity. Even more than in the other countries of the Eastern Bloc, the men of the car nation of Eastern Europe were skilled car mechanics. The Škodas, Ladas, Tatras and Wartburgs were looked after and cared for, they were dismantled, oiled, serviced and, if necessary, repaired by hand. The garages were well-equipped workshops. Tools of all kinds hung on the walls. It smelled of lubricating oil, beer and sweat. Faded calendar pictures of busty blondes stuck to the walls and toolboxes and awakened early longings in the adolescent. The men drank beer and Slivovice and talked about pistons, gears and horsepower. A perfect world for a boy. In socialist times, going to the garage replaced going to church on Sundays. The garage was the home of the car, but also a place of escape and freedom. Before the celebratory family outing, the car was rolled out of the garage, washed and spruced up. Cleaning the car had almost cult dimensions. Women also helped with this ritual. Our neighbor Miroslav Tichy also liked to come here and take photos of the women bending down or getting out of their cars. But more about that in other books. Everything was beautiful in front of the garages on Sunday – the women and the cars were shining and the men were wearing white, freshly ironed shirts. The stories of my fathers and grandfathers are intertwined in my memories with the stories of their cars. As a boy, I admired the men and their cars. My paternal grandfather was called Herman and owned a car called “Polularka.” It was old and had to be started by hand. Every trip began with “starting the Popularka.” Grandma and I were ready for the trip and watched Grandfather with excitement. First, Grandfather rolled up his sleeves and opened the hood. With a tense face, he turned and screwed the levers and adjusting screws of the carburetor, checked the spark plugs, the cables and the fuel tap. Then grandfather knelt down in front of Popularka and stuck a crank into a hole in the engine. He said to Popularka, telling her to be a good girl and start the engine properly this time. Then grandfather cranked the engine hard and swore, as Popularka would not start for a long time. Although his curses were hardly understandable because grandfather always had a cigarette in the corner of his mouth, grandmother scolded him, telling him not to talk so rudely in front of the child. When Popularka finally started, grandfather had to quickly get into the car, accelerate and fiddle with various levers to give Popularka the right mixture of petrol and air. Only when the engine roared loudly had we won and grandfather’s face beamed with a broad smile. Now grandmother sat in the passenger seat and accelerated with her left foot, while grandfather worked the crank and closed the bonnet. The trip could begin. In summer we usually drove to the pond in Milotice. It was always exciting to see whether Popularka would manage the hill that separated us from our destination or whether she would come to a standstill with the engine smoking. When the engine started to sputter, Popularka naturally had to be talked to again or even scolded.

Shortly after my birth, my father and mother took me from Prague to Kyjov in a laundry basket on the back seat of an Opel Olympia to show me to my father’s family. The Opel Olympia belonged to my mother’s father, Vladimir, and was built in 1952, just four years older than me. Grandfather Vladimir was the son of a simple railway employee in Karlštejn. He came from a poor background, but was hardworking and skilled. After an apprenticeship as a blacksmith, he became a toolmaker in the Kolben Danek machine factory in Prague and is said to have had two hundred workers under him in the 1920s. His innate skill and energy in the workshop were legendary. I remember the stories of his heroic deeds. When he once again dared to make the long journey from Karlštejn near Prague to Kyjov in the Moravian province to visit his family, the engine’s piston burst just before Kyjov. The following day, grandfather paid a visit to the comrades at the screw factory in Kyjov, where he cast a new piston from steel based on the damaged original. The next day, the repaired car with the brand new, hand-made piston drove flawlessly 300 km back from Kyjov to Prague. That’s how skilled my grandfather Vladimir was. The men who shaped my original families couldn’t have been more different. On my father’s side, there were farmers’ sons who worked their way up to become entrepreneurs, Jewish ancestors, merchants, owners of a soda factory, or dentists like my grandfather Rudek, who wrote plays and recorded records on his musical saw before he was killed in Majdanek in the summer of 1942. And then there was the workshop master Vladimir. On my mother’s side, there were stories of noblemen and horse dealers, railway workers and hard-working workers. Cars and horses were the companions of all my ancestors. On my mother’s side, the Pejsa family had been involved in the horse trade for generations. Great-grandfather Josef Kopečný from Kyjov had made a rapid rise from farmer’s son to saddler and strap maker in Kyjov. At the end of the First World War and thanks to the Spanish flu, he had set up the “Pieta” funeral home in addition to the saddlery. When he then married a trained artificial flower maker who brought the necessary aesthetic know-how in decorating corpses, horses and coffins to the business, the family was able to buy one of the first cars in Kyjov in the 1920s. What a rise in Svatoborská. Horses have been decisive for the development of our cultures for tens of thousands of years. The wheel, the plough and wars were not fought by people, but by people and horses. The age of horses is hardly imaginable in the age of horsepower and fossil fuels. Memory is so short, remembering so difficult. In thousands of years, the horse transformed Eurasia. The wheel, the plow, the saddle, the stirrups, and the war on horseback changed the world. It was only a hundred or two hundred years ago that horses were replaced by machines – cars, tanks, airplanes, submarines. And garages replaced horse stables. When grandfather Vladimir was already ninety, his 1952 Opel Olympia was standing on wooden trestles in the garden in Karlštejn. “I’m on my last legs,” he would say, gently stroking the hood of the equally disabled car. It was clear that this car was dear to his heart and that he shared his fate. I bought the vehicle from him and decided to restore it. The goal was to ceremoniously drive through Karlštejn with my grandfather and celebrate a victory over time and decay. Grandfather died. My mother died. And the car is still not finished. The window seals are still missing and I still want to continue the heroic deeds of my ancestors in the field of automobiles. But I haven’t given up yet.

Unlike in the Swiss cities that I got to know after emigrating in 1968, garages in Czechoslovakia were not integrated into the residential buildings. The housing estates in the Eastern Bloc were built without garages. Firstly, the prefabricated buildings of the 1950s were much cheaper without the expensive underground garages. Secondly, the car was not an everyday vehicle – it was only needed on Sundays. The socialist workers’ housing estates were built on the outskirts of the city, where there was enough cheap building land. So the garages were built some distance away from the housing estates. The garages were built in rows like honeycombs and were all the same: a body made of three concrete slabs and a flat roof. So small cities for cars were built next to the housing estates for the workers. Man and machine were treated equally. Socialist urbanism reorganized the villages. The prefabricated buildings for the people, the garages for the cars and the cemeteries for the dead. The front of a garage was closed off by a gate. Like all other components of the garage, the gate was also prefabricated. The garages and therefore the gates were all the same size. First, a steel frame was covered with wooden planks. Over time, different “models” were used in which the steel frame was fitted with sheet metal plates. To ensure the stability of the garage door leaves, the frame of each leaf had to be reinforced. This was done using cross-shaped struts. Four sheet metal parts were then usually welded onto these “crosses”. The gate was now ready to be installed. The gate to the man’s paradise, however, had to be protected from earthly things. The weather, wind and temperature fluctuations cause iron to rust. As a preventative measure, the man has to paint his garage door. First, the old paint residue is removed with a gas burner and rusty metal parts are sanded off. A primer will be the painter’s first important job. When the primer is dry, it usually has to be sanded again. Then the man has to show his colors. What color should the garage door be? Red? Green? The same color as the neighbor? The same color as last year? A color that no one else has? Or do you just take a leftover that you find in the garage? Color does not represent emotion, here color is a concept. The painter is not doing it for fun! He does not want to express feelings. No room for expression. Not De Kooning or Arnulf Rainer, here the inspiration is Ives Klein and Günther Förg. Gate after gate, monochrome after monochrome, limb after limb, the rows tightly closed, high and still higher! Since the “New Wild” we have been looking for the immediacy of painterly expression. We wanted to get away from academic painting and towards the naive and the amateur. Many of us drew with our left hand back then. A fellow student at the Munich Academy guided the brush with her anal muscle and impressed Daniel Spörri’s entire class. Güther Förg told me that he had his cleaning lady make certain large-format canvases, giving her small sketches on paper as a template. From Baselitz and Penk to Andy Hope in 1930 and Jonathan Meese, painters sought the unaffected, authentic picture that only a layman, a child or a madman could paint. Or someone who painted his garage door. Private painting work in real social life was not carried out by professional painters. The painter was the man who owned the garage. The garage door was the gate to his paradise – or at least an image of it, a kind of abstract self-portrait. The garage doors are paintings by men who of course did not see themselves as artists. They paint – because they have to paint! The garage doors are amateur paintings. They lack anything artificial, any mannerism, any urge for decoration, expression, ornament. Every door is a painting that makes the painter visible. His stroke, the choice of color, the way he applied the paint, everything gives us an idea of the author. No two gate pictures are the same. A picture by an unknown painter, with no artistic intentions. To paint a large area with as little color as possible in as short a time as possible, well enough to protect the gate from rust for a long time and beautiful enough not to be embarrassed in front of the neighbors.

A grey winter day is ideal for taking pictures in natural light. Together with Ondřej Polák I photographed eighteen garages, which I selected based on painterly criteria. Ondřej Polák is a sought-after museum photographer in Prague, specialising in photographing paintings and exhibitions. I asked Ondřej to treat the garages like paintings. We photographed on Kodak E 100 film (9 x 13 cm positives) and then enlarged them on Kodak Endura photo paper. I had the unique pieces mounted in oak frames. I chose a height of 80 cm as the format, which was half the height of the garages, or about a quarter of the area of the garage door. A quadrangle is a special scale – too big for a model and too small for a replica of reality.”

- RB (December 2024)