Kunst macht frei

1991–1992

“Shortly after the fall of the Iron Curtain, my paternal grandmother passed away, but not before experiencing the return of the house in Kyjov, which had been confiscated and “nationalized” by the Communists. This was a great relief for her. Only then could she let go and die.

As a child, I loved sneaking up to the attic of that house. It was dark, warm in the summer, and full of mysteries. Under a thick layer of dust lay the treasures of generations. I discovered the dentist’s chair of my grandfather Rudolf Buxbaum, whom I never met because he was murdered as a Jew in Lublin Majdanek in 1942. In a box, I found black paper flowers made by my great-grandmother, used for funerals. My great-grandparents, the Kopecnys, ran the thriving funeral home Pieta. Also destined for funerals were horse harnesses and enormous black drapes that were laid over the horses’ backs. In many cabinets, chests, and boxes, I found letters, files, magazines, and photographs, which I spent hours studying as a child.

Now, this ancestral treasure, along with the house, became mine. At the time, I was preoccupied with memories and history. What to do? Clear it out and throw everything away? No! I ordered a truck. My grandmother’s attic was loaded onto it and transported to Switzerland. My mother, who at the time commuted between Baden and Karlštejn, where she was caring for her elderly father, came along. When the Swiss customs officer saw the contents of the truck, he reportedly took three steps back and crossed himself. My mother tried to calm him down: “Look at the crazy son I have! This is trash, nothing but trash. And he’s spending money to have it transported to Switzerland. Completely crazy! And I have to deal with it.” We didn’t have to pay customs.

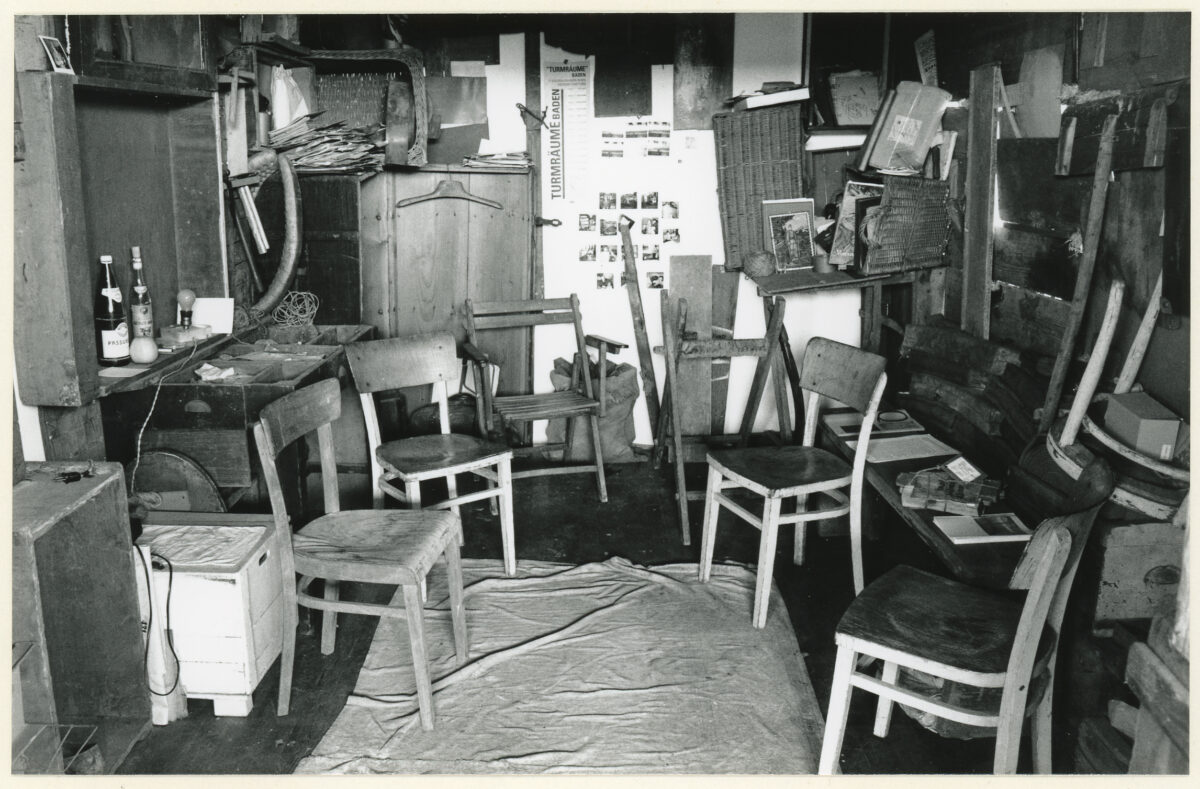

The truck drove to Aarau, where I had an exhibition at Kunstraum Aarau. From the ancestral trash, I built an ancestral hut. It was cozy. Chairs, a table, and plenty of slivovitz – also part of my grandmother’s estate. Even her stove worked after we installed a vent pipe through one of the Kunstraum’s windows. The exiled Czechs came. We burned the remains of the furniture sacrificed for the hut. Earth to earth, ashes to ashes. We gathered in the hut, drank slivovitz, and shared stories – memories.

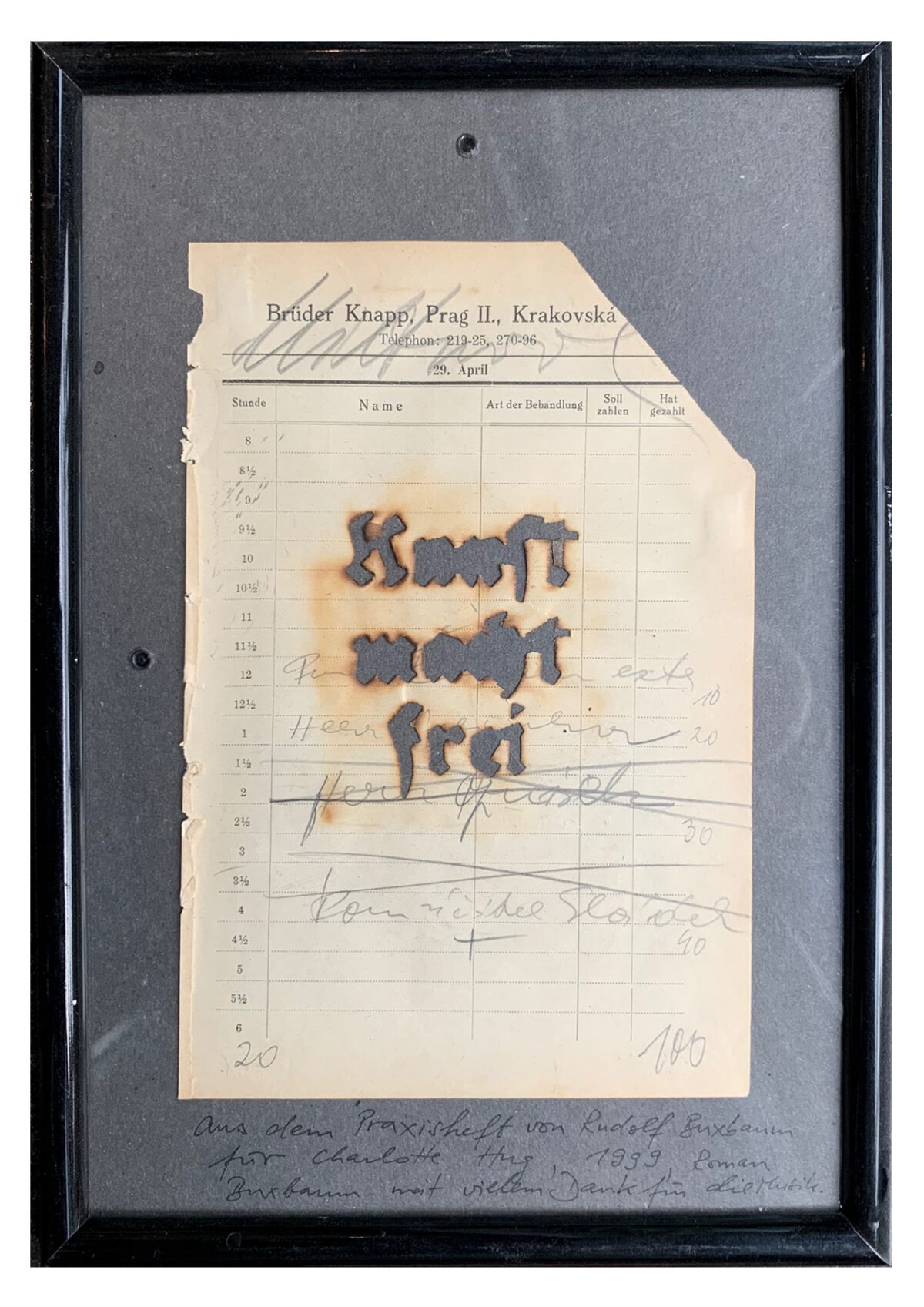

When the exhibition ended, the truck returned. The next stop was Centre Pasquart – Kunsthaus Biel, where I was given the opportunity to create a large solo exhibition in eight rooms. Everything was moved into one of the rooms, where I set up a sawbuck and a saw I had found in the attic. The ancestral hut was turned into kindling there. With a branding iron, I burned the words “KUNST MACHT FREI” (Art Sets You Free) into the wood pieces. What was once a tree, then became furniture – a table or a cabinet belonging to my great-grandfather – was now wood again, freed even from my great-grandfather.

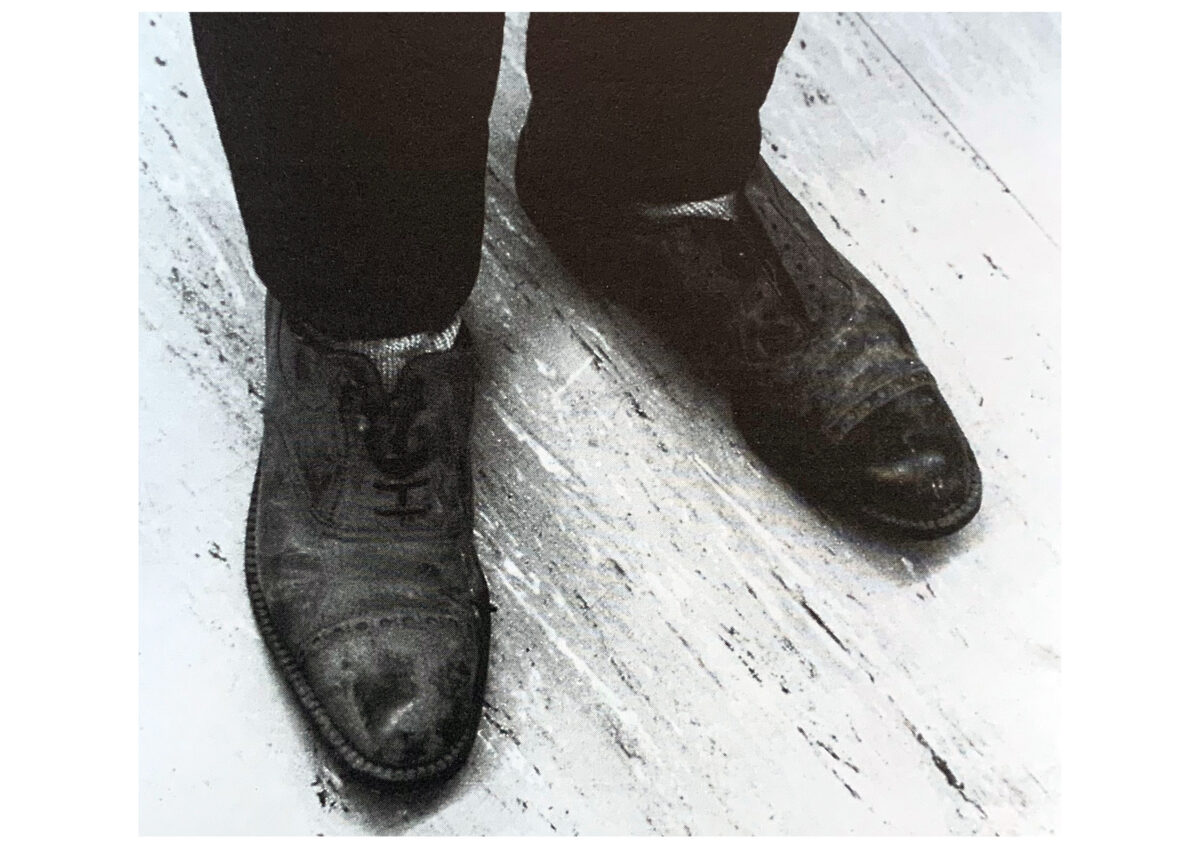

After Biel, only a small delivery van was needed. The kindling fit into a few boxes. There were still a few pieces of furniture, an old television, a couple of suitcases with documents, my grandfather’s shoes, and my chamber pot. The journey continued to Czechoslovakia, to Brno. There, I had an exhibition in the famous underground gallery “Na Bidýlku,” which had shown banned artists for decades during the communist dictatorship without interference.

The gallery space had a rectangular floor plan. I built a structure in the middle of the room that divided it in two. Into the structure, we packed everything: the boxes, television, and suitcases. Visitors could only approach the structure. Through the gaps between the ancestral objects, they could see the other half of the room. It was empty.

After the “Na Bidýlku” exhibition, I hired a delivery van for the final journey. From Brno, it’s only 30 kilometers to Kyjov. We brought everything back to where it had come from – to my grandmother’s attic. And there it remains to this day. And if they haven’t died yet…”

RB, December 2024

“Shortly after the fall of the Iron Curtain, my paternal grandmother passed away, but not before experiencing the return of the house in Kyjov, which had been confiscated and “nationalized” by the Communists. This was a great relief for her. Only then could she let go and die.

As a child, I loved sneaking up to the attic of that house. It was dark, warm in the summer, and full of mysteries. Under a thick layer of dust lay the treasures of generations. I discovered the dentist’s chair of my grandfather Rudolf Buxbaum, whom I never met because he was murdered as a Jew in Lublin Majdanek in 1942. In a box, I found black paper flowers made by my great-grandmother, used for funerals. My great-grandparents, the Kopecnys, ran the thriving funeral home Pieta. Also destined for funerals were horse harnesses and enormous black drapes that were laid over the horses’ backs. In many cabinets, chests, and boxes, I found letters, files, magazines, and photographs, which I spent hours studying as a child.

Now, this ancestral treasure, along with the house, became mine. At the time, I was preoccupied with memories and history. What to do? Clear it out and throw everything away? No! I ordered a truck. My grandmother’s attic was loaded onto it and transported to Switzerland. My mother, who at the time commuted between Baden and Karlštejn, where she was caring for her elderly father, came along. When the Swiss customs officer saw the contents of the truck, he reportedly took three steps back and crossed himself. My mother tried to calm him down: “Look at the crazy son I have! This is trash, nothing but trash. And he’s spending money to have it transported to Switzerland. Completely crazy! And I have to deal with it.” We didn’t have to pay customs.

The truck drove to Aarau, where I had an exhibition at Kunstraum Aarau. From the ancestral trash, I built an ancestral hut. It was cozy. Chairs, a table, and plenty of slivovitz – also part of my grandmother’s estate. Even her stove worked after we installed a vent pipe through one of the Kunstraum’s windows. The exiled Czechs came. We burned the remains of the furniture sacrificed for the hut. Earth to earth, ashes to ashes. We gathered in the hut, drank slivovitz, and shared stories – memories.

When the exhibition ended, the truck returned. The next stop was Centre Pasquart – Kunsthaus Biel, where I was given the opportunity to create a large solo exhibition in eight rooms. Everything was moved into one of the rooms, where I set up a sawbuck and a saw I had found in the attic. The ancestral hut was turned into kindling there. With a branding iron, I burned the words “KUNST MACHT FREI” (Art Sets You Free) into the wood pieces. What was once a tree, then became furniture – a table or a cabinet belonging to my great-grandfather – was now wood again, freed even from my great-grandfather.

After Biel, only a small delivery van was needed. The kindling fit into a few boxes. There were still a few pieces of furniture, an old television, a couple of suitcases with documents, my grandfather’s shoes, and my chamber pot. The journey continued to Czechoslovakia, to Brno. There, I had an exhibition in the famous underground gallery “Na Bidýlku,” which had shown banned artists for decades during the communist dictatorship without interference.

The gallery space had a rectangular floor plan. I built a structure in the middle of the room that divided it in two. Into the structure, we packed everything: the boxes, television, and suitcases. Visitors could only approach the structure. Through the gaps between the ancestral objects, they could see the other half of the room. It was empty.

After the “Na Bidýlku” exhibition, I hired a delivery van for the final journey. From Brno, it’s only 30 kilometers to Kyjov. We brought everything back to where it had come from – to my grandmother’s attic. And there it remains to this day. And if they haven’t died yet…”

RB, December 2024