Mein Kunst – Totale Kunst (My art – Total art)

1989–1999

After the fall of the communist regime in November 1989, Roman Buxbaum spent a lot of time in Prague. He became friends with main personas of the newly formed and finally free contemporary art scene, such as artist Jiří David or a curatorial couple Jana Ševčíková and Jiří Ševčík.

He was invited to exhibit in the newly free galleries in Prague such as “U Řečických” in 1991 and eight years later, in 1999, he showcased a solo exhibition at the Rudolfinum Gallery, Prague’s for a long time only Kunsthalle.

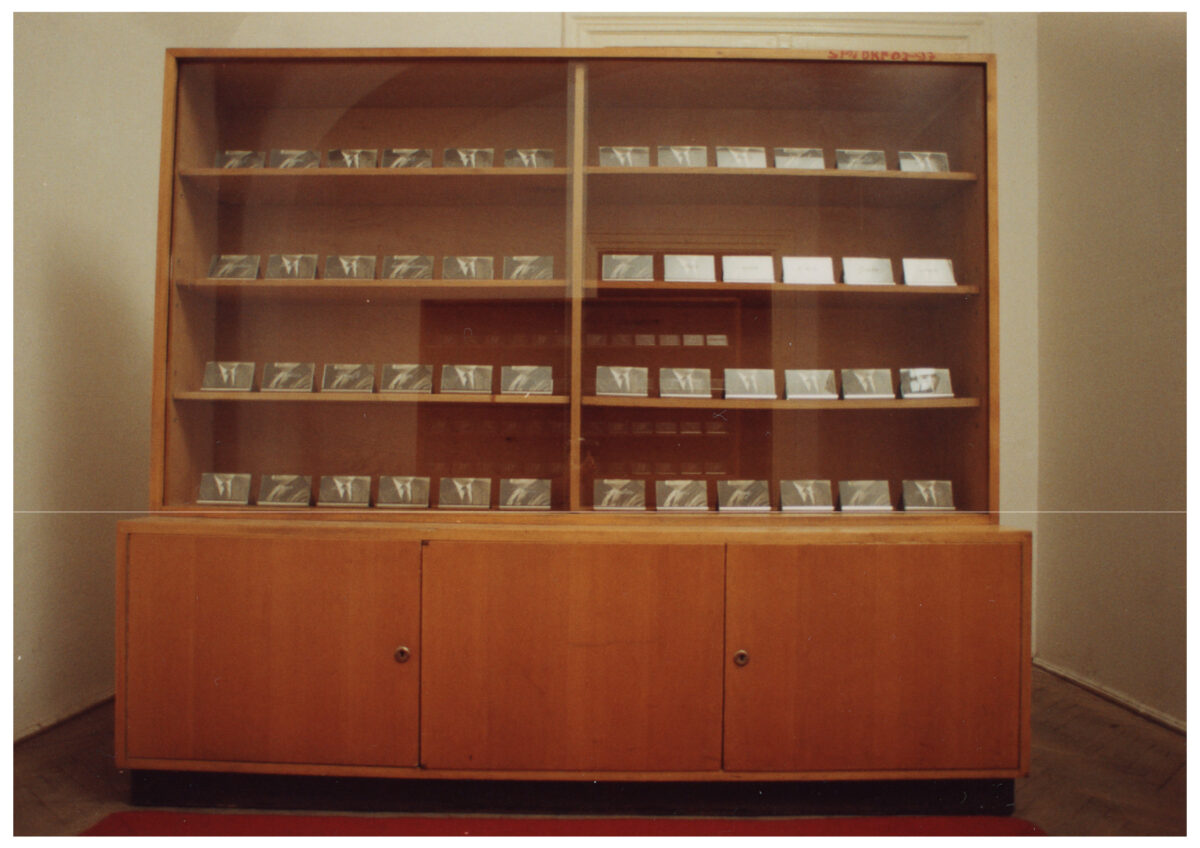

Buxbaum recalls the exhibition U Řečických: “I showed there the work ‘Polohlavy – Half Heads’. This installation was created from objects that I discovered in a neighboring house near the gallery. The house was home to a communist publishing company, which shut down after the revolution. The house was deserted. The typical furniture of the 1960s was everywhere. In one of the cupboards I found a box with carefully arranged cards on which words in Polish and Czech were written. Apparently an employee was learning Polish and made these cards to practice. The image on the back of the cards was interesting. It was the lower half of the head of Josef Stalin and his counterpart Gottwald, President of Czechoslovakia until 1956. Half heads. I had a glass grinder make small standing frames and grind the word written on the other side into the glass. The frames were then placed in cabinets from the office of the communist publishing house, where I found the cards. I laid a red carpet between the cabinets.”

*****

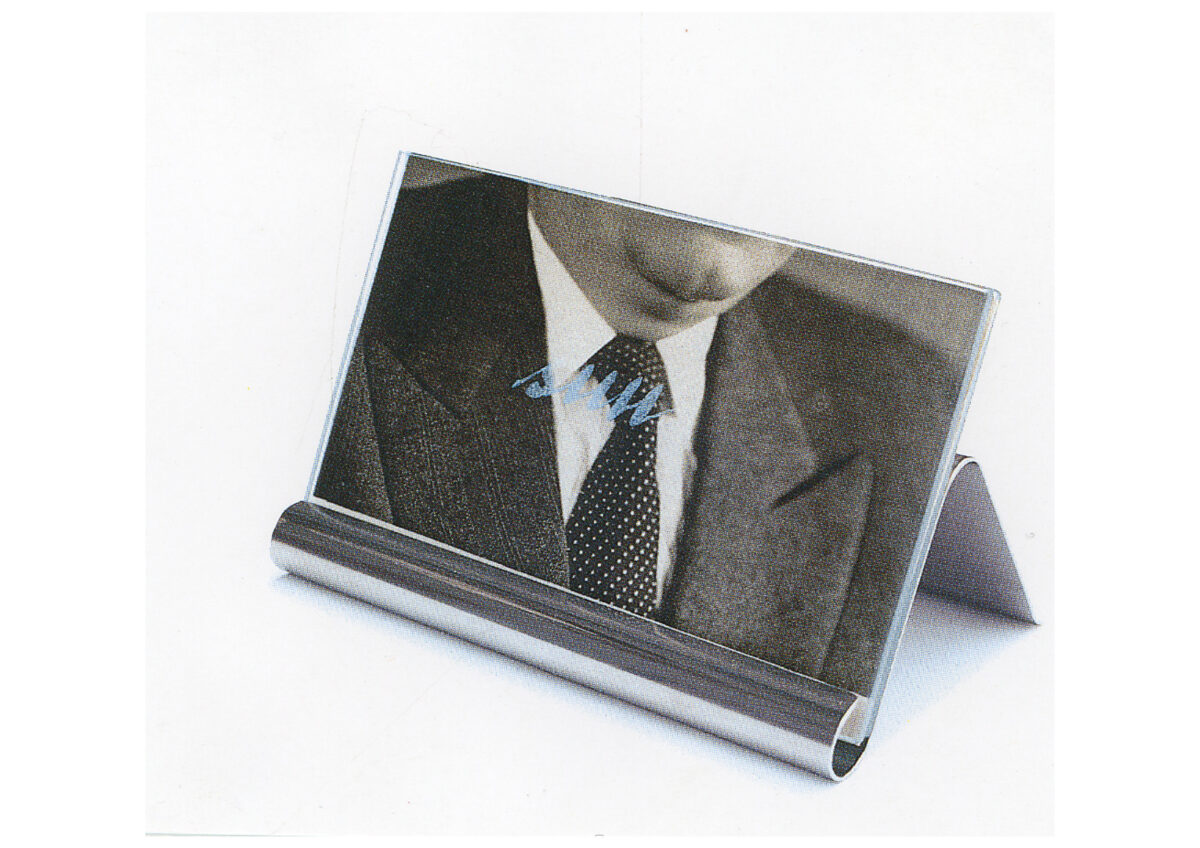

The exhibition in the Rudolfinum referred to another monstrous dictator of 20th century history: Adolf Hitler.

“I was particularly interested in the young Hitler – the failed artist. As far as I know, there is only one book from the 1970s that documents Hitler’s entire artistic work and I had to have it. In the end, I had to steal it from a library. It contains all of his drawings. I began photographing and cataloging them. The drawings are so bad that it is no surprise that Hitler was rejected by the academy twice, but that he applied twice. This shows that even then his connection to reality was distorted and his ego was almost delusional. In the Rudolfinum, I showed two slide projections: ‘The Towers’and ‘The Mother’. Hitler liked to draw towers. There were hundreds of them. I projected them over each other, fading in and out, giving the impression of a tower that was slowly changing. ‘The Mother’ was a complex installation based on a Madonna with a child in her arms. Another installation dealt with the xenophobia of the Czech population. After the Velvet Revolution, many Roma and Szinti came to Czechoslovakia from Romania and Hungary. The ‘gypsies’ are hated by the Czechs and new racist jokes are constantly being created. I have loved Jewish jokes since I was twelve or thirteen and read Erika Landmann’s DTV booklet ‘The Jewish Joke’ and of course later Martin Buber. It occurred to me that the jokes are similar, but they are also different. The ‘gypsy jokes’ are told by the Czechs; the Jewish jokes by the Jews. I wanted to investigate this and asked some young Roma to tell me jokes in front of the camera, then some Holocaust survivors and finally some native Prague Germans (who survived the deportations after the Beneš Decrees). We played the interviews on six monitors in a room so that the viewers could move from one joke to the next. Only the narrators really laughed. There was also a telephone in this room. It was a beautiful, old device from the 1950s, made of black Bakelite, with a dial of course and a spiral cable. I also took it with me from the abandoned publishing house. It stood on a pedestal and rang every now and then. We put up a sign asking exhibition visitors to pick up the phone. The day before, we handed out little leaflets at metro stations. We also placed an ad in the newspapers: ‘Do you have something against gypsies? Do you have something against Jews? Call us! Tel: 02/248 933 15’ We set up the telephone number just for this campaign.”

– RB, December 2024

After the fall of the communist regime in November 1989, Roman Buxbaum spent a lot of time in Prague. He became friends with main personas of the newly formed and finally free contemporary art scene, such as artist Jiří David or a curatorial couple Jana Ševčíková and Jiří Ševčík.

He was invited to exhibit in the newly free galleries in Prague such as “U Řečických” in 1991 and eight years later, in 1999, he showcased a solo exhibition at the Rudolfinum Gallery, Prague’s for a long time only Kunsthalle.

Buxbaum recalls the exhibition U Řečických: “I showed there the work ‘Polohlavy – Half Heads’. This installation was created from objects that I discovered in a neighboring house near the gallery. The house was home to a communist publishing company, which shut down after the revolution. The house was deserted. The typical furniture of the 1960s was everywhere. In one of the cupboards I found a box with carefully arranged cards on which words in Polish and Czech were written. Apparently an employee was learning Polish and made these cards to practice. The image on the back of the cards was interesting. It was the lower half of the head of Josef Stalin and his counterpart Gottwald, President of Czechoslovakia until 1956. Half heads. I had a glass grinder make small standing frames and grind the word written on the other side into the glass. The frames were then placed in cabinets from the office of the communist publishing house, where I found the cards. I laid a red carpet between the cabinets.”

*****

The exhibition in the Rudolfinum referred to another monstrous dictator of 20th century history: Adolf Hitler.

“I was particularly interested in the young Hitler – the failed artist. As far as I know, there is only one book from the 1970s that documents Hitler’s entire artistic work and I had to have it. In the end, I had to steal it from a library. It contains all of his drawings. I began photographing and cataloging them. The drawings are so bad that it is no surprise that Hitler was rejected by the academy twice, but that he applied twice. This shows that even then his connection to reality was distorted and his ego was almost delusional. In the Rudolfinum, I showed two slide projections: ‘The Towers’and ‘The Mother’. Hitler liked to draw towers. There were hundreds of them. I projected them over each other, fading in and out, giving the impression of a tower that was slowly changing. ‘The Mother’ was a complex installation based on a Madonna with a child in her arms. Another installation dealt with the xenophobia of the Czech population. After the Velvet Revolution, many Roma and Szinti came to Czechoslovakia from Romania and Hungary. The ‘gypsies’ are hated by the Czechs and new racist jokes are constantly being created. I have loved Jewish jokes since I was twelve or thirteen and read Erika Landmann’s DTV booklet ‘The Jewish Joke’ and of course later Martin Buber. It occurred to me that the jokes are similar, but they are also different. The ‘gypsy jokes’ are told by the Czechs; the Jewish jokes by the Jews. I wanted to investigate this and asked some young Roma to tell me jokes in front of the camera, then some Holocaust survivors and finally some native Prague Germans (who survived the deportations after the Beneš Decrees). We played the interviews on six monitors in a room so that the viewers could move from one joke to the next. Only the narrators really laughed. There was also a telephone in this room. It was a beautiful, old device from the 1950s, made of black Bakelite, with a dial of course and a spiral cable. I also took it with me from the abandoned publishing house. It stood on a pedestal and rang every now and then. We put up a sign asking exhibition visitors to pick up the phone. The day before, we handed out little leaflets at metro stations. We also placed an ad in the newspapers: ‘Do you have something against gypsies? Do you have something against Jews? Call us! Tel: 02/248 933 15’ We set up the telephone number just for this campaign.”

– RB, December 2024