Onko Journal

2009

The following text is a personal diary of Roman Buxbaum describing the time the artist was dealing with oncological disease.

Onco Diary, August 2009

Since receiving the diagnosis of anal carcinoma on July 3, 2009, I’ve been hyper-aware of my rear end and acting like an ass. I believe I’m annoying everyone around me. As a doctor, I interfere in the work of the nurses and physicians, though they endure me patiently. People say that if you make a mess, you’ve got to deal with it.

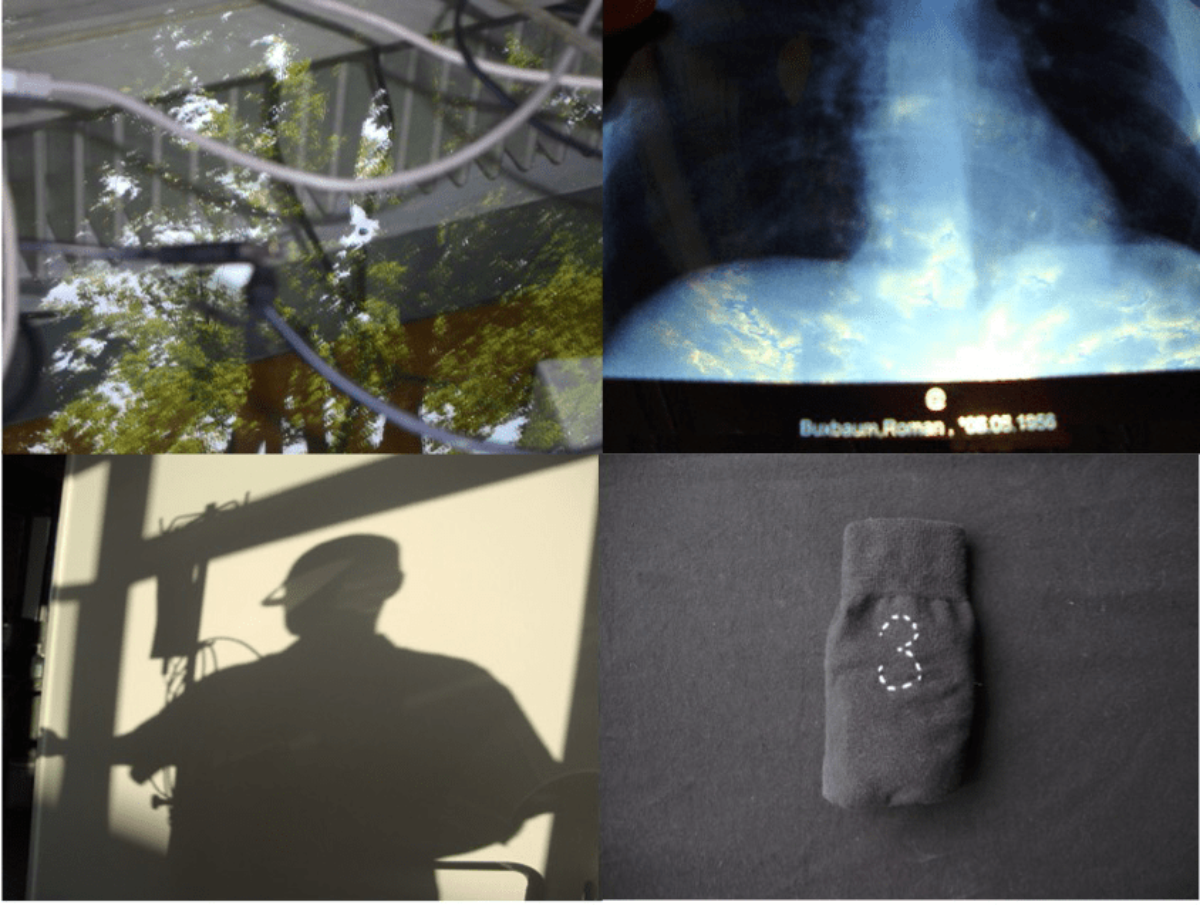

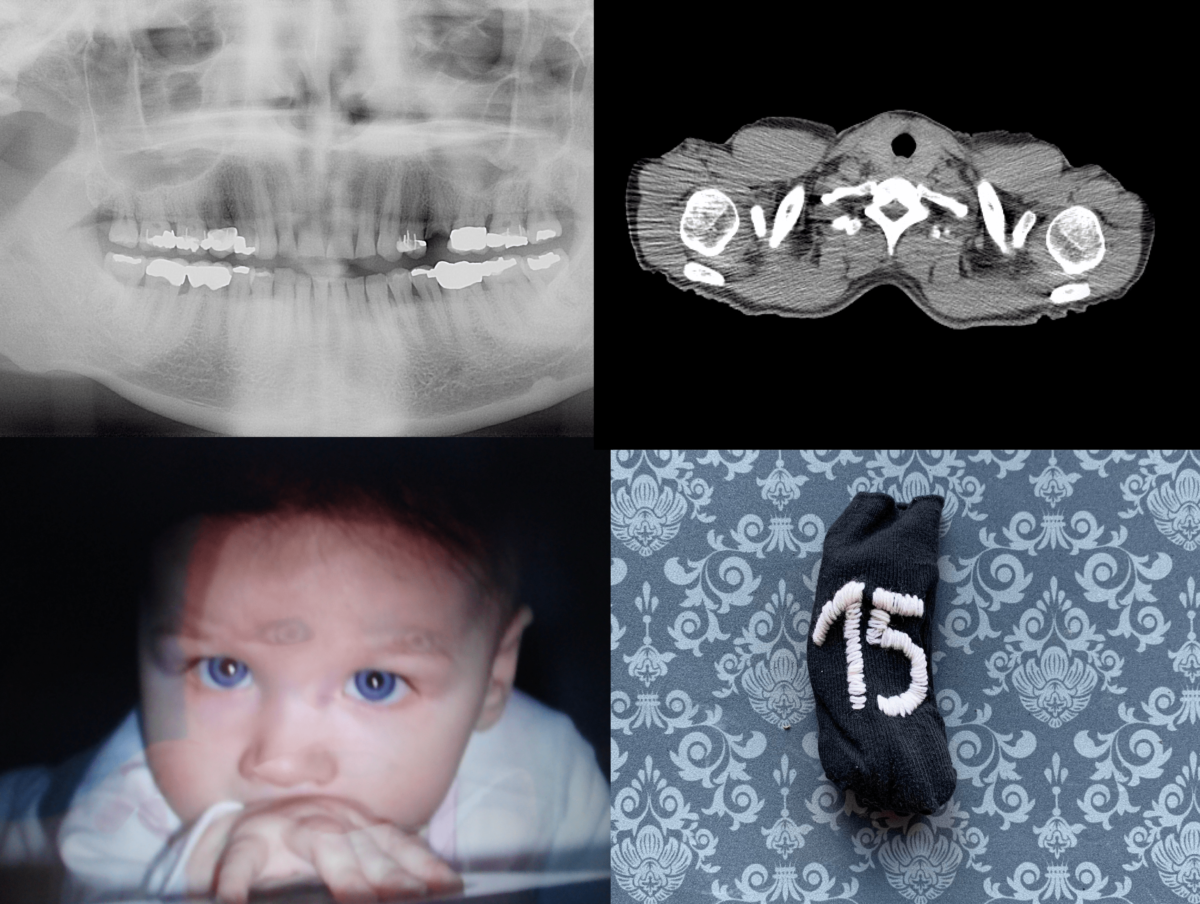

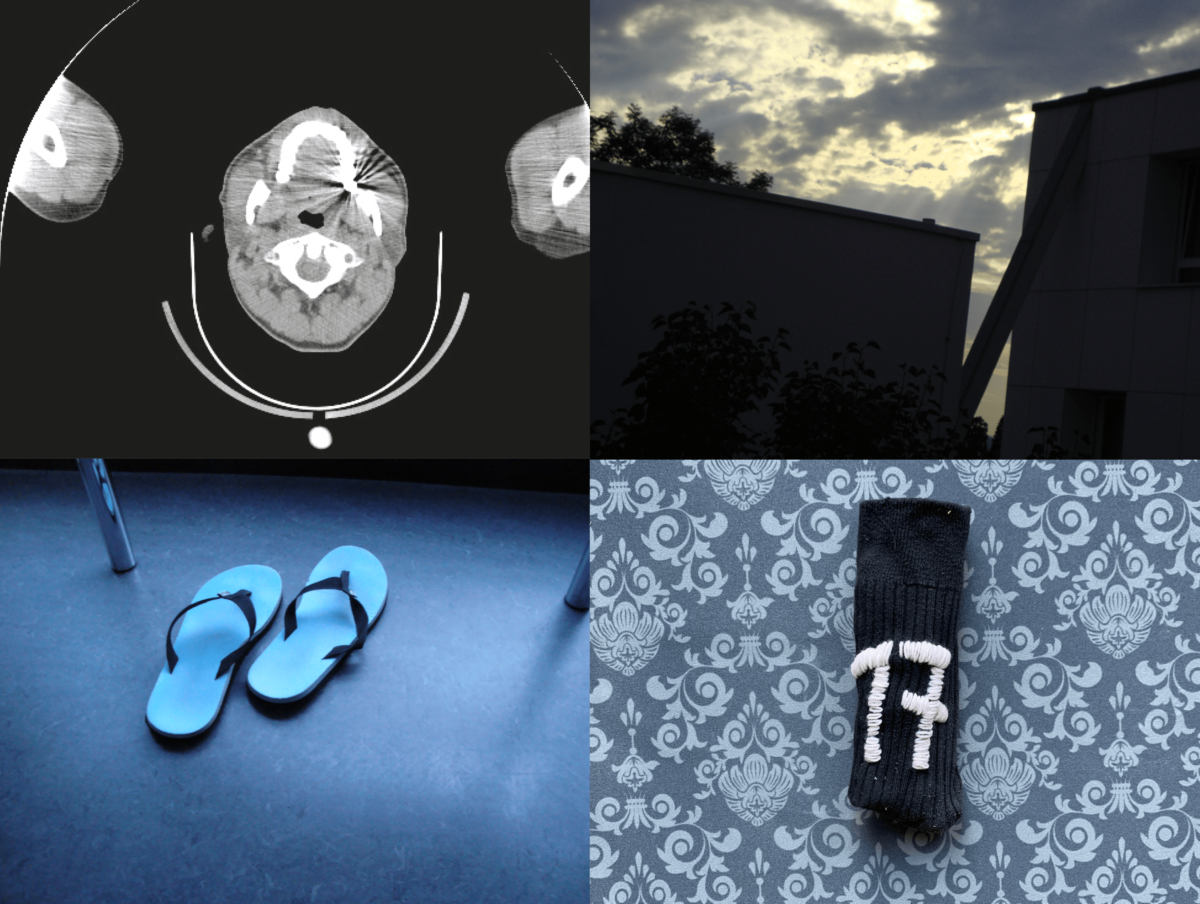

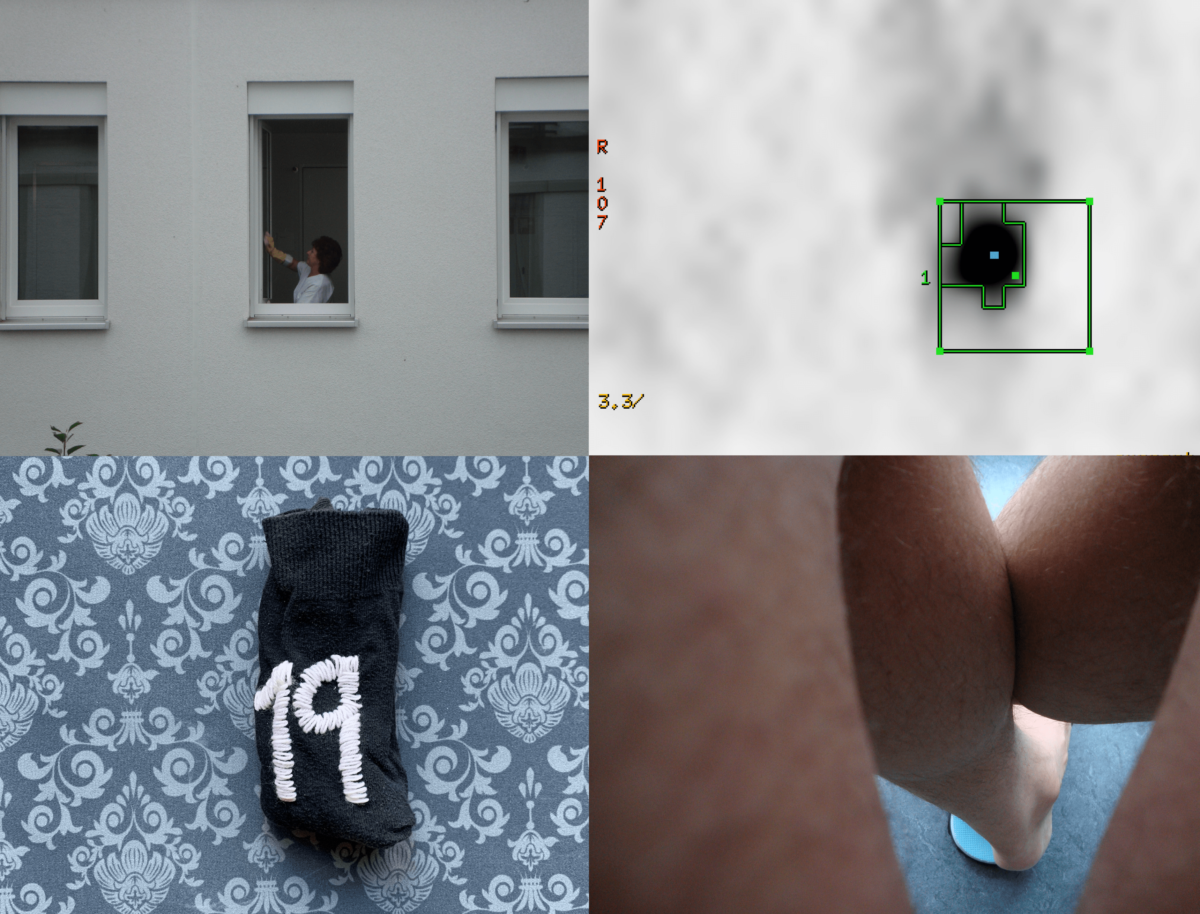

As an artist, I need to process my very personal mess artistically. Talking doesn’t help me much, though I can’t entirely resist verbal outbursts. Writing, however, does help. So, here I am in the Hirslanden hospital, writing this text, taking photos, and hoping to get through it all. The treatment won’t be pleasant and will last 20 days. Particularly the second cycle of radiation and chemotherapy will bring pain and unpleasant side effects. I will suffer. A pastor friend who visited me recently mentioned someone who had passed away from pancreatic cancer, saying the man had “softened” in the end. Pancreatic cancer had swiftly taken him. “He was soft as butter at the end,” he said.

Heaven help me, I thought. When pain and decay torment you, when morphine makes you sick and you can barely breathe, you might indeed become an egg without a shell. I’ve always despised the sugarcoating and romanticizing of suffering. They remind me of religious kitsch, prevalent across all denominations—whether it’s a 3D close-up of the crucified Christ, whose expression suggests erotic ecstasy rather than pain, or a weeping boy with crocodile tears on his round cheeks and a red, half-open pout. Is suffering meant to enchant?

I brought 20 pairs of black socks with me. One new pair for each day. I’m embroidering numbers on each pair, from one to twenty. Tomorrow morning, I’ll put on the first pair. When I take them off in the evening, there’ll be 19 pairs left in the closet.

I used to be carcinophobic; now I have a carcinoma. If I survive this, I plan to have every organ without an orifice scanned regularly and all orifices examined endoscopically. Perhaps prophylactically removing the prostate, pancreas, and other likely killer organs would offer the ultimate security—ensuring that dementia is the only way to die. In the film The Green Mile, a prisoner asks for one last visit to the restroom. The guard reassures him, “Don’t worry, everyone soils themselves during execution.” As the soul leaves the body, all of life’s waste empties out one last time. Yet the prisoner doesn’t want to die a mess. His shame over losing sphincter control outweighs his fear of death. That surprised me.

In the thriller The Taking of Pelham 123, the villain recalls a story about sled dogs in Alaskan ice. The dogs defecate while running because they must. Later, in prison, the main character reflects on this and turns it into a parable of survival under extreme conditions. Do what you must!

I’m terrified. My mind is flooded with anal metaphors as the embodiment of death: the fear that makes us soil ourselves; Dante’s “anus” as the exit from hell; feces as the ultimate shorthand for mortality. Auschwitz latrines, images of death.

We take the natural functioning of our organs for granted, only recognizing them when they fail. Less familiar ones, like the spleen or pancreas, we only notice as sources of illness. How unjust! We should give thanks daily: “Dear liver, heart, lungs, and circulation, dear white blood cells, thank you for working tirelessly all day and serving me so well.” When my heart stops at 70, I should say: “You brave pump! You worked nonstop for seventy years, never oiled, repaired, or cleaned. Thank you—it’s a miracle you lasted this long!”

Onco Diary, May 2014

It’s been five years now. Three weeks ago, my oncologist said goodbye with the words, “It’s better you don’t come anymore. The chances of finding a recurrence of the anal carcinoma are smaller than discovering a new tumor.” I shook his hand and left. Outside the hospital, I lit a cigarette and called a friend. “I just lost my oncologist,” I told her, “and I’ll miss him.” She didn’t understand. “At least I’ll dedicate a book to him,” I continued. “He was an important person to me. I had endless conversations with him—inner dialogues, of course. He was rather taciturn, never wasted a word. But he was a friend.” My friend hung up. Wrong friend, I thought.

When I entered the oncology department at the Hirslanden Clinic in Zurich in August 2009, I didn’t bring Solzhenitsyn’s Cancer Ward. I came armed with a camera, an Apple Macintosh laptop, sewing supplies, paper, and pens. These were my tools to confront the horrors of reality.

Dr. B., my oncologist, greeted me with genuine joy: “You’re my absolute favorite tumor among the patients I’m treating right now. Man, everyone here would want your tumor!” He promised me a five-year recurrence rate of less than 10%. “Ask the lung cancer patient next door what he’d give for those odds!” Dr. B. was both cheerful and a pessimist—two traits that aren’t mutually exclusive. “I’m amazed I’m still alive,” he said. “After all the cancers I’ve seen, young and old, I’m astonished I don’t have one myself. You know what? That helps me enjoy every day as if it were my last. Carry death on your left shoulder, young man. Plant an apple tree today!”

He encouraged me. I was relieved. He didn’t know about the tumor on my left shoulder that I’d declared an artwork years earlier. Reality often outshines art.

Today, the important thing was that the doctors saw me as someone still alive, not someone about to dissolve or mummify—life’s two farewell options for biological tissue. The nurses, less inclined to differentiate between tumors, smiled kindly at all their future corpses.

Now, after my recovery, I’ve decided to reclaim my identity as an artist. Life goes on—scarred, but still here. Fuck it!

The following text is a personal diary of Roman Buxbaum describing the time the artist was dealing with oncological disease.

Onco Diary, August 2009

Since receiving the diagnosis of anal carcinoma on July 3, 2009, I’ve been hyper-aware of my rear end and acting like an ass. I believe I’m annoying everyone around me. As a doctor, I interfere in the work of the nurses and physicians, though they endure me patiently. People say that if you make a mess, you’ve got to deal with it.

As an artist, I need to process my very personal mess artistically. Talking doesn’t help me much, though I can’t entirely resist verbal outbursts. Writing, however, does help. So, here I am in the Hirslanden hospital, writing this text, taking photos, and hoping to get through it all. The treatment won’t be pleasant and will last 20 days. Particularly the second cycle of radiation and chemotherapy will bring pain and unpleasant side effects. I will suffer. A pastor friend who visited me recently mentioned someone who had passed away from pancreatic cancer, saying the man had “softened” in the end. Pancreatic cancer had swiftly taken him. “He was soft as butter at the end,” he said.

Heaven help me, I thought. When pain and decay torment you, when morphine makes you sick and you can barely breathe, you might indeed become an egg without a shell. I’ve always despised the sugarcoating and romanticizing of suffering. They remind me of religious kitsch, prevalent across all denominations—whether it’s a 3D close-up of the crucified Christ, whose expression suggests erotic ecstasy rather than pain, or a weeping boy with crocodile tears on his round cheeks and a red, half-open pout. Is suffering meant to enchant?

I brought 20 pairs of black socks with me. One new pair for each day. I’m embroidering numbers on each pair, from one to twenty. Tomorrow morning, I’ll put on the first pair. When I take them off in the evening, there’ll be 19 pairs left in the closet.

I used to be carcinophobic; now I have a carcinoma. If I survive this, I plan to have every organ without an orifice scanned regularly and all orifices examined endoscopically. Perhaps prophylactically removing the prostate, pancreas, and other likely killer organs would offer the ultimate security—ensuring that dementia is the only way to die. In the film The Green Mile, a prisoner asks for one last visit to the restroom. The guard reassures him, “Don’t worry, everyone soils themselves during execution.” As the soul leaves the body, all of life’s waste empties out one last time. Yet the prisoner doesn’t want to die a mess. His shame over losing sphincter control outweighs his fear of death. That surprised me.

In the thriller The Taking of Pelham 123, the villain recalls a story about sled dogs in Alaskan ice. The dogs defecate while running because they must. Later, in prison, the main character reflects on this and turns it into a parable of survival under extreme conditions. Do what you must!

I’m terrified. My mind is flooded with anal metaphors as the embodiment of death: the fear that makes us soil ourselves; Dante’s “anus” as the exit from hell; feces as the ultimate shorthand for mortality. Auschwitz latrines, images of death.

We take the natural functioning of our organs for granted, only recognizing them when they fail. Less familiar ones, like the spleen or pancreas, we only notice as sources of illness. How unjust! We should give thanks daily: “Dear liver, heart, lungs, and circulation, dear white blood cells, thank you for working tirelessly all day and serving me so well.” When my heart stops at 70, I should say: “You brave pump! You worked nonstop for seventy years, never oiled, repaired, or cleaned. Thank you—it’s a miracle you lasted this long!”

Onco Diary, May 2014

It’s been five years now. Three weeks ago, my oncologist said goodbye with the words, “It’s better you don’t come anymore. The chances of finding a recurrence of the anal carcinoma are smaller than discovering a new tumor.” I shook his hand and left. Outside the hospital, I lit a cigarette and called a friend. “I just lost my oncologist,” I told her, “and I’ll miss him.” She didn’t understand. “At least I’ll dedicate a book to him,” I continued. “He was an important person to me. I had endless conversations with him—inner dialogues, of course. He was rather taciturn, never wasted a word. But he was a friend.” My friend hung up. Wrong friend, I thought.

When I entered the oncology department at the Hirslanden Clinic in Zurich in August 2009, I didn’t bring Solzhenitsyn’s Cancer Ward. I came armed with a camera, an Apple Macintosh laptop, sewing supplies, paper, and pens. These were my tools to confront the horrors of reality.

Dr. B., my oncologist, greeted me with genuine joy: “You’re my absolute favorite tumor among the patients I’m treating right now. Man, everyone here would want your tumor!” He promised me a five-year recurrence rate of less than 10%. “Ask the lung cancer patient next door what he’d give for those odds!” Dr. B. was both cheerful and a pessimist—two traits that aren’t mutually exclusive. “I’m amazed I’m still alive,” he said. “After all the cancers I’ve seen, young and old, I’m astonished I don’t have one myself. You know what? That helps me enjoy every day as if it were my last. Carry death on your left shoulder, young man. Plant an apple tree today!”

He encouraged me. I was relieved. He didn’t know about the tumor on my left shoulder that I’d declared an artwork years earlier. Reality often outshines art.

Today, the important thing was that the doctors saw me as someone still alive, not someone about to dissolve or mummify—life’s two farewell options for biological tissue. The nurses, less inclined to differentiate between tumors, smiled kindly at all their future corpses.

Now, after my recovery, I’ve decided to reclaim my identity as an artist. Life goes on—scarred, but still here. Fuck it!