Paintings on wood

since 2017

“Where can I find a person who forgets words so that I can talk to him?” Zhuāngzi

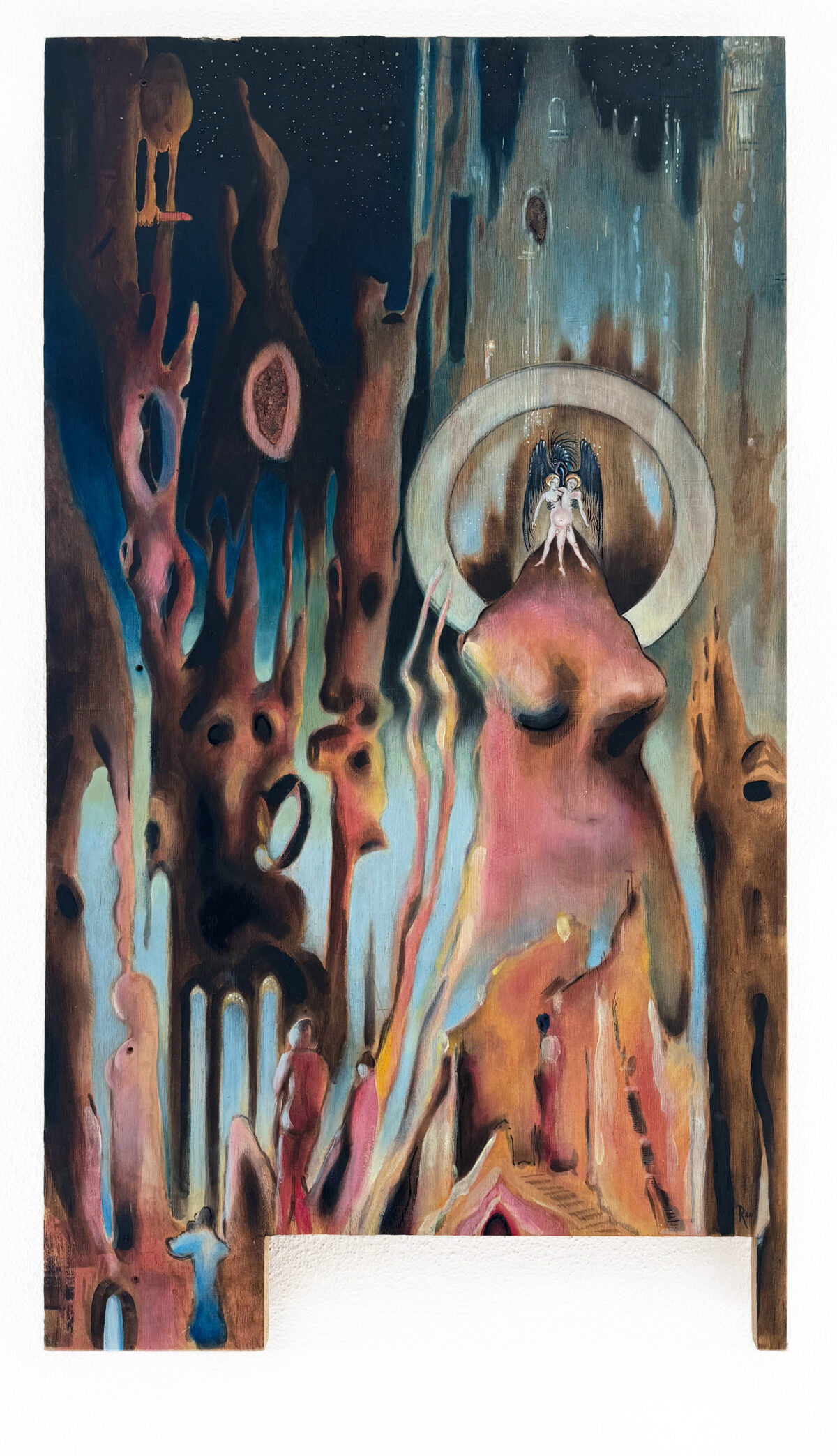

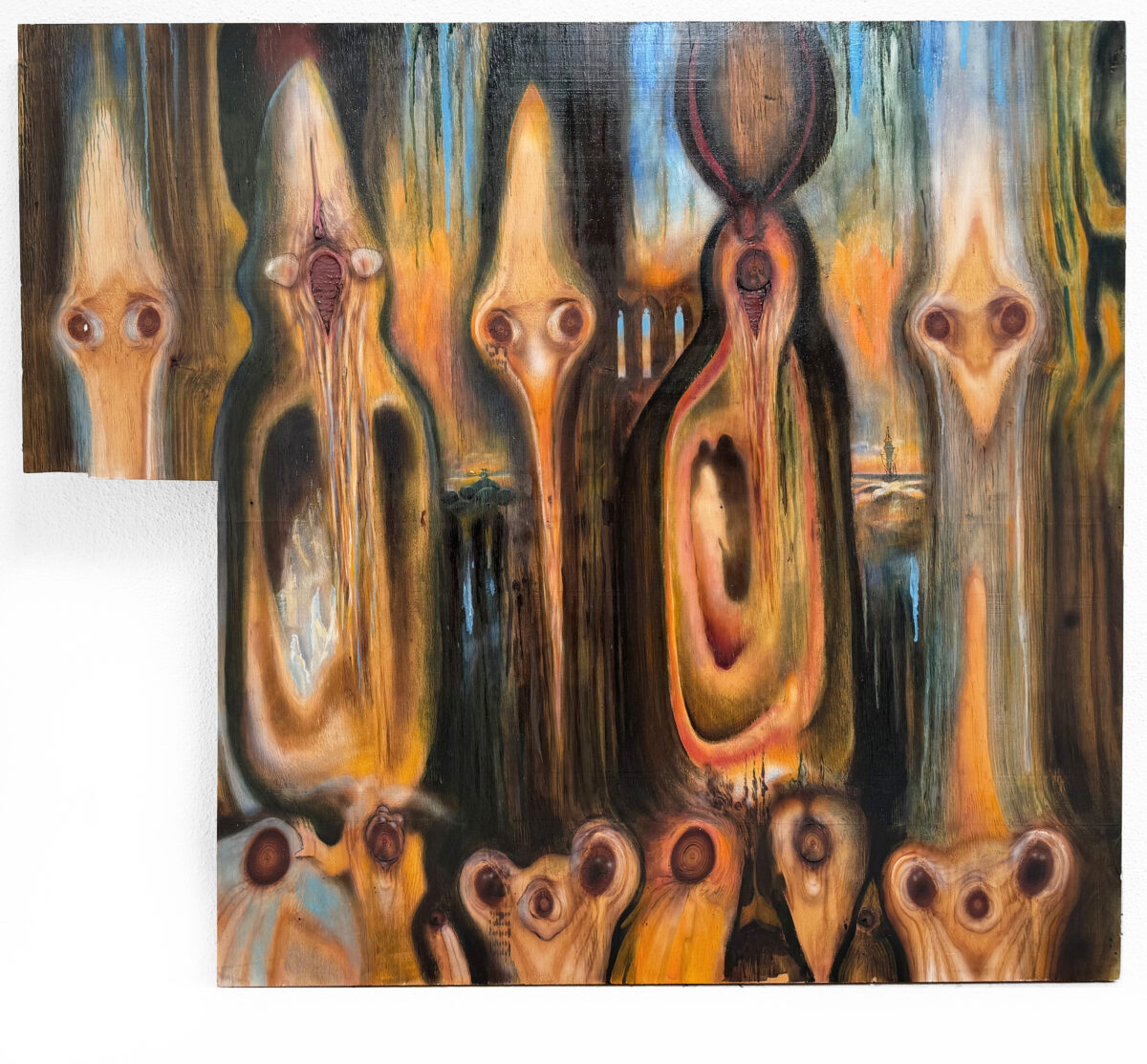

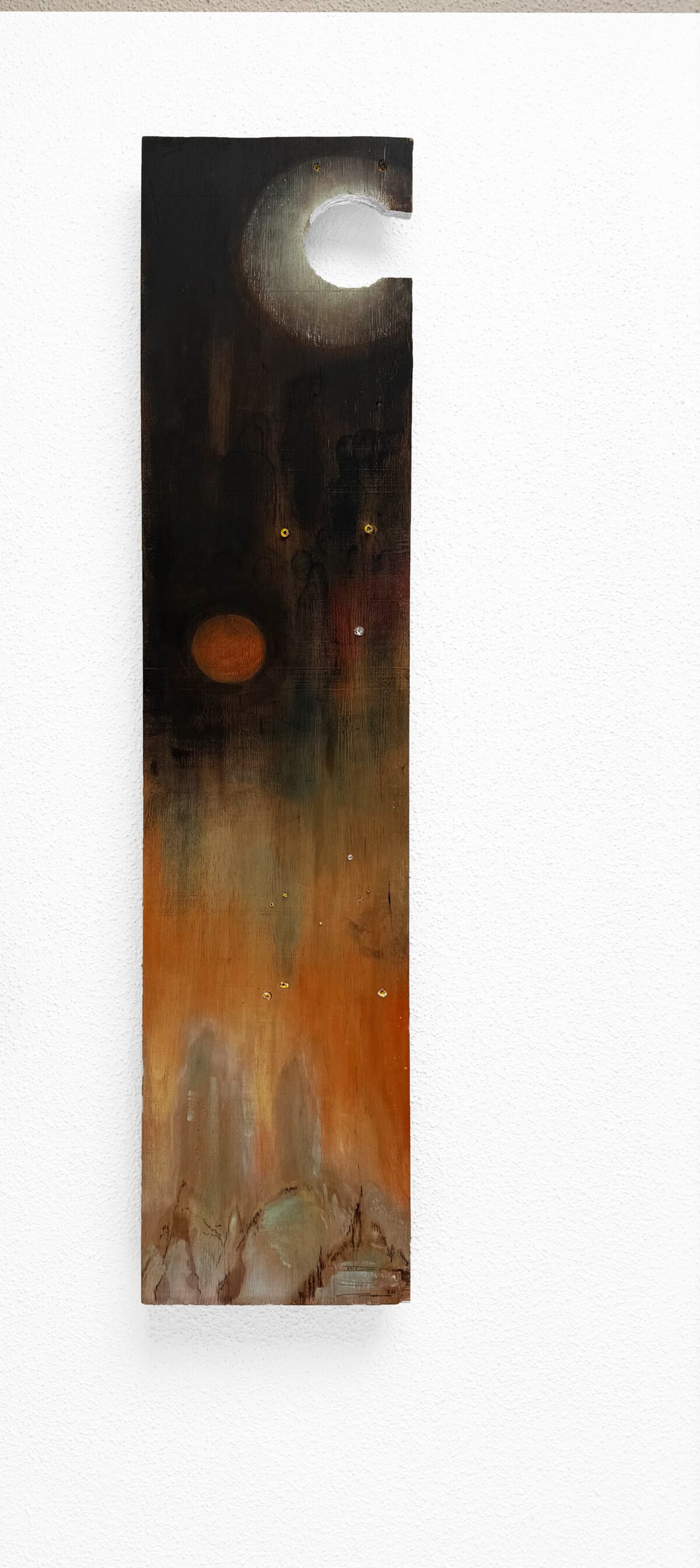

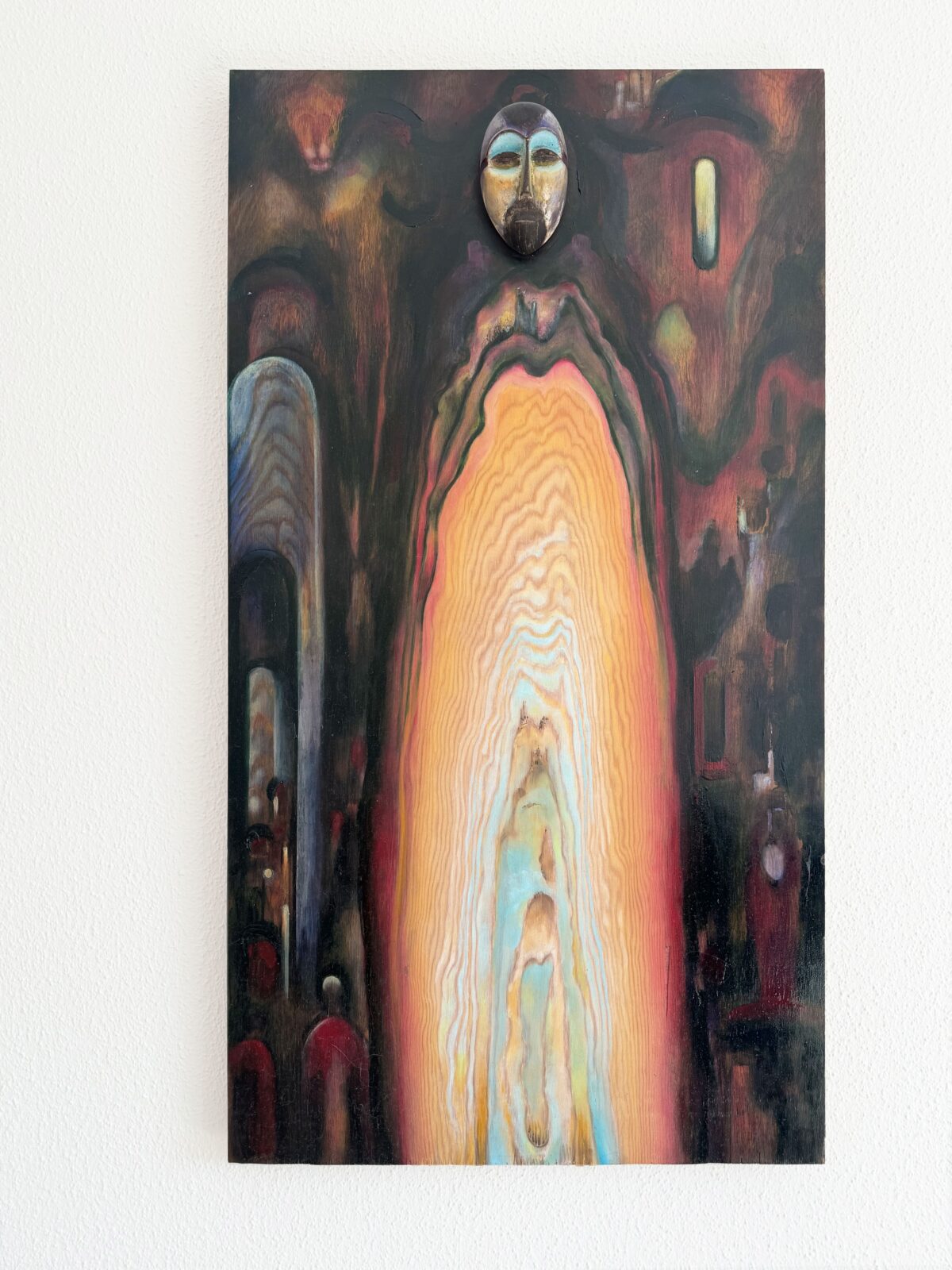

“As I get older, the essential seems more unsayable to me, or more precisely – the unsayable more essential. Artistically, I have increasingly abandoned previous media of expression (most recently the audience-interactive theater performance) and returned to painting. Getting by without words is the great freedom of painting. The person I speak to is the picture. I only paint for myself, rarely letting visitors into the studio. It interrupts my silent dialogue with the picture. It is like when two lovers look deeply into each other’s eyes and a third person enters the room. I am ashamed; I feel caught. I can imagine that my pictures might have something to say to others, but I don’t necessarily want to be there. I started drawing and painting when I was twelve. But I didn’t like the white, empty canvas. I preferred to use painting surfaces that already had a structure, a life of their own and a history that I could react to. I drew on yellowed, stained cardboard and painted on printed fabrics, deck chairs and discarded wooden shutters. And on discarded pictures that I bought in thrift stores. The first wooden pictures were created in the 1970s. I found discarded window sills, table tops and chair remnants that I could paint. Objects that had a history as objects of use behind them, but were now discarded and useless. Doomed, they could, like dying stars, become the raw material for new galaxies. That invited me to paint. And of course the structure of the wood. In the Dao, “Li” means the grain of the wood, also called “wood image” and is interpreted as the structural law of being. The grain is the image of the annual rings on a cut piece of wood. It is created by the natural growth behavior and growth anomalies of a tree. Depending on the type of wood, it appears plain, wavy, striped, spotted, flaming or whimpering. The grain also depends on the direction of the cut, with the annual rings visible in the cross-section, the veins in the tangential cut and the medullary rays in the radial cut. The natural structure of the wood can be strengthened with fire. This old Japanese technique of wood preservation is called Yakisugi. By slightly charring the wood surface, the wood becomes water-repellent and more durable through carbonization. The carbonized layer also protects against insect and fungal attack. Yaki means ‘burn’, Sugi is the Japanese name for ‘six-pine’. Literally translated, it means “burnt six-pine board”. A wooden surface is carbonized through controlled burning and then sealed with oil. The metaphor behind Shou Sugi Ban is deeply rooted in Japanese culture. In western countries it is sometimes also called Shou Sugi Ban. I use maritime pine panels, which I treat with a gas burner so that only the soft wood layers turn black. This creates patterns that serve as a starting point for painting. For my wooden pictures I prefer maritime pine plywood panels. They are cheap, available in any hardware store and have a lively grain. Folding the veneer layers over results in large-format symmetrical shapes that stimulate my imagination. Like in a Rorschach test, I see figures of monks, heads of demons, breasts, genitals, cities and castles, skies and seas full of moons and stars. Often I see a distant landscape. I – the observer – am far away. I float like a drone above the foreground. The foreground and the background open up a deep and distant space, the kind I love in the landscapes of the Romantic period. The picture can begin with a large, glaze-like application of paint or, on the contrary, with a tiny detail that I discover in the wood. During the entire painting process, I oscillate between the colored areas and the details in the wood, between the large and small brushes. I follow the wood and not a preconceived idea of the picture. This is how surprises arise, which I follow. Even in the late phase of the picture, when the front and back, top and bottom are already defined, I let myself go and break through the picture architecture again. I only paint what is there, what I really see, not what I want to paint. The world here is everything that is the case and not will and imagination.

Another source of visual images flows into my painting. I call them hypnagogic images and I see them just before I fall asleep. Sometimes they are small scenes that appear in the middle of the field of vision when my eyes are closed, in a tunnel or some kind of cave. They are miniatures that appear sharply against the background of the blurred field of vision for a fraction of a second, transform and then disappear. These small, sometimes moving images show groups of people that remind me of scenes in Renaissance paintings. I like to use these miniatures in my paintings – figures or small landscapes that nestle in the picture in small grottos and caves. These images in the picture are painted sharply and on a different scale than the picture as a whole. As in medieval painting, here I leave the perspective space in favor of a space of meaning, another world that has nestled in the large-format picture reality. When I lie there awake with my eyes closed, I also observe patterns and colors. When I paint, I try to incorporate these colors into the picture. To do this, I usually have to paint a dark background first, over which lighter colors are then applied in a glaze. Because the colors that I see behind closed eyes appear to me as being built up light on dark. By touching my closed eyes, wonderful color transitions and afterimages appear. I paint what I see with my eyes closed. The structure of the wood allows me to start the picture without any intention and without a predetermined motif. It’s like a game of chess. With my largest brush, I open up the first transparent areas of color with diluted oil paint, which can develop into figures or landscapes (usually both) with increasing layers. I follow the wood and only paint what the wood “shows” me. The scale, the perspective, the incidence of light, the technique and the mood often change within the picture. From abstraction to figuration and back. It’s like a dream. When I paint, my attention quickly oscillates between my eyes and my hands. The brain then switches to a kind of dream state. The “wooden picture” is particularly suitable for this self-hypnosis. When I immerse myself in the wood patterns, I enter an altered, dissociative state of consciousness. I abandon the rules of “sensible” image composition in favor of psychedelic vision. I paint to experience this state. As a small boy, I liked to sit on my grandmother’s toilet and stare at the door. The white paint on the door was old and cracked, craquellé you would say. The toilet was small and my head was close to the door, so I could only see the many small crack patterns on the door out of focus. This door opened up the world of fantasy, of visual ecstasy. Intensity always finds its medium. I found the wood and within it a whole universe. The plywood is my James Webb telescope. I paint to look at the cosmos.”

- RB (December 2024)

“Where can I find a person who forgets words so that I can talk to him?” Zhuāngzi

“As I get older, the essential seems more unsayable to me, or more precisely – the unsayable more essential. Artistically, I have increasingly abandoned previous media of expression (most recently the audience-interactive theater performance) and returned to painting. Getting by without words is the great freedom of painting. The person I speak to is the picture. I only paint for myself, rarely letting visitors into the studio. It interrupts my silent dialogue with the picture. It is like when two lovers look deeply into each other’s eyes and a third person enters the room. I am ashamed; I feel caught. I can imagine that my pictures might have something to say to others, but I don’t necessarily want to be there. I started drawing and painting when I was twelve. But I didn’t like the white, empty canvas. I preferred to use painting surfaces that already had a structure, a life of their own and a history that I could react to. I drew on yellowed, stained cardboard and painted on printed fabrics, deck chairs and discarded wooden shutters. And on discarded pictures that I bought in thrift stores. The first wooden pictures were created in the 1970s. I found discarded window sills, table tops and chair remnants that I could paint. Objects that had a history as objects of use behind them, but were now discarded and useless. Doomed, they could, like dying stars, become the raw material for new galaxies. That invited me to paint. And of course the structure of the wood. In the Dao, “Li” means the grain of the wood, also called “wood image” and is interpreted as the structural law of being. The grain is the image of the annual rings on a cut piece of wood. It is created by the natural growth behavior and growth anomalies of a tree. Depending on the type of wood, it appears plain, wavy, striped, spotted, flaming or whimpering. The grain also depends on the direction of the cut, with the annual rings visible in the cross-section, the veins in the tangential cut and the medullary rays in the radial cut. The natural structure of the wood can be strengthened with fire. This old Japanese technique of wood preservation is called Yakisugi. By slightly charring the wood surface, the wood becomes water-repellent and more durable through carbonization. The carbonized layer also protects against insect and fungal attack. Yaki means ‘burn’, Sugi is the Japanese name for ‘six-pine’. Literally translated, it means “burnt six-pine board”. A wooden surface is carbonized through controlled burning and then sealed with oil. The metaphor behind Shou Sugi Ban is deeply rooted in Japanese culture. In western countries it is sometimes also called Shou Sugi Ban. I use maritime pine panels, which I treat with a gas burner so that only the soft wood layers turn black. This creates patterns that serve as a starting point for painting. For my wooden pictures I prefer maritime pine plywood panels. They are cheap, available in any hardware store and have a lively grain. Folding the veneer layers over results in large-format symmetrical shapes that stimulate my imagination. Like in a Rorschach test, I see figures of monks, heads of demons, breasts, genitals, cities and castles, skies and seas full of moons and stars. Often I see a distant landscape. I – the observer – am far away. I float like a drone above the foreground. The foreground and the background open up a deep and distant space, the kind I love in the landscapes of the Romantic period. The picture can begin with a large, glaze-like application of paint or, on the contrary, with a tiny detail that I discover in the wood. During the entire painting process, I oscillate between the colored areas and the details in the wood, between the large and small brushes. I follow the wood and not a preconceived idea of the picture. This is how surprises arise, which I follow. Even in the late phase of the picture, when the front and back, top and bottom are already defined, I let myself go and break through the picture architecture again. I only paint what is there, what I really see, not what I want to paint. The world here is everything that is the case and not will and imagination.

Another source of visual images flows into my painting. I call them hypnagogic images and I see them just before I fall asleep. Sometimes they are small scenes that appear in the middle of the field of vision when my eyes are closed, in a tunnel or some kind of cave. They are miniatures that appear sharply against the background of the blurred field of vision for a fraction of a second, transform and then disappear. These small, sometimes moving images show groups of people that remind me of scenes in Renaissance paintings. I like to use these miniatures in my paintings – figures or small landscapes that nestle in the picture in small grottos and caves. These images in the picture are painted sharply and on a different scale than the picture as a whole. As in medieval painting, here I leave the perspective space in favor of a space of meaning, another world that has nestled in the large-format picture reality. When I lie there awake with my eyes closed, I also observe patterns and colors. When I paint, I try to incorporate these colors into the picture. To do this, I usually have to paint a dark background first, over which lighter colors are then applied in a glaze. Because the colors that I see behind closed eyes appear to me as being built up light on dark. By touching my closed eyes, wonderful color transitions and afterimages appear. I paint what I see with my eyes closed. The structure of the wood allows me to start the picture without any intention and without a predetermined motif. It’s like a game of chess. With my largest brush, I open up the first transparent areas of color with diluted oil paint, which can develop into figures or landscapes (usually both) with increasing layers. I follow the wood and only paint what the wood “shows” me. The scale, the perspective, the incidence of light, the technique and the mood often change within the picture. From abstraction to figuration and back. It’s like a dream. When I paint, my attention quickly oscillates between my eyes and my hands. The brain then switches to a kind of dream state. The “wooden picture” is particularly suitable for this self-hypnosis. When I immerse myself in the wood patterns, I enter an altered, dissociative state of consciousness. I abandon the rules of “sensible” image composition in favor of psychedelic vision. I paint to experience this state. As a small boy, I liked to sit on my grandmother’s toilet and stare at the door. The white paint on the door was old and cracked, craquellé you would say. The toilet was small and my head was close to the door, so I could only see the many small crack patterns on the door out of focus. This door opened up the world of fantasy, of visual ecstasy. Intensity always finds its medium. I found the wood and within it a whole universe. The plywood is my James Webb telescope. I paint to look at the cosmos.”

- RB (December 2024)