Performances and Theater

1990 – 2003

After the exhibition “Mein Kunst” at the Rudolfinum Gallery in Prague (1999), Buxbaum developed the theme further in a performative way. In the performance “Come with Me into Himmler’s Bed!” at the Kunstverein Oberberg in Stuttgart (1995), he read “Love Letters to Adolf Hitler.”

In other performances – this time at the Theater am Neumarkt (in Zurich, 2001), Buxbaum brought to life his haunting dreams about Holocaust when he recited them on the stage:

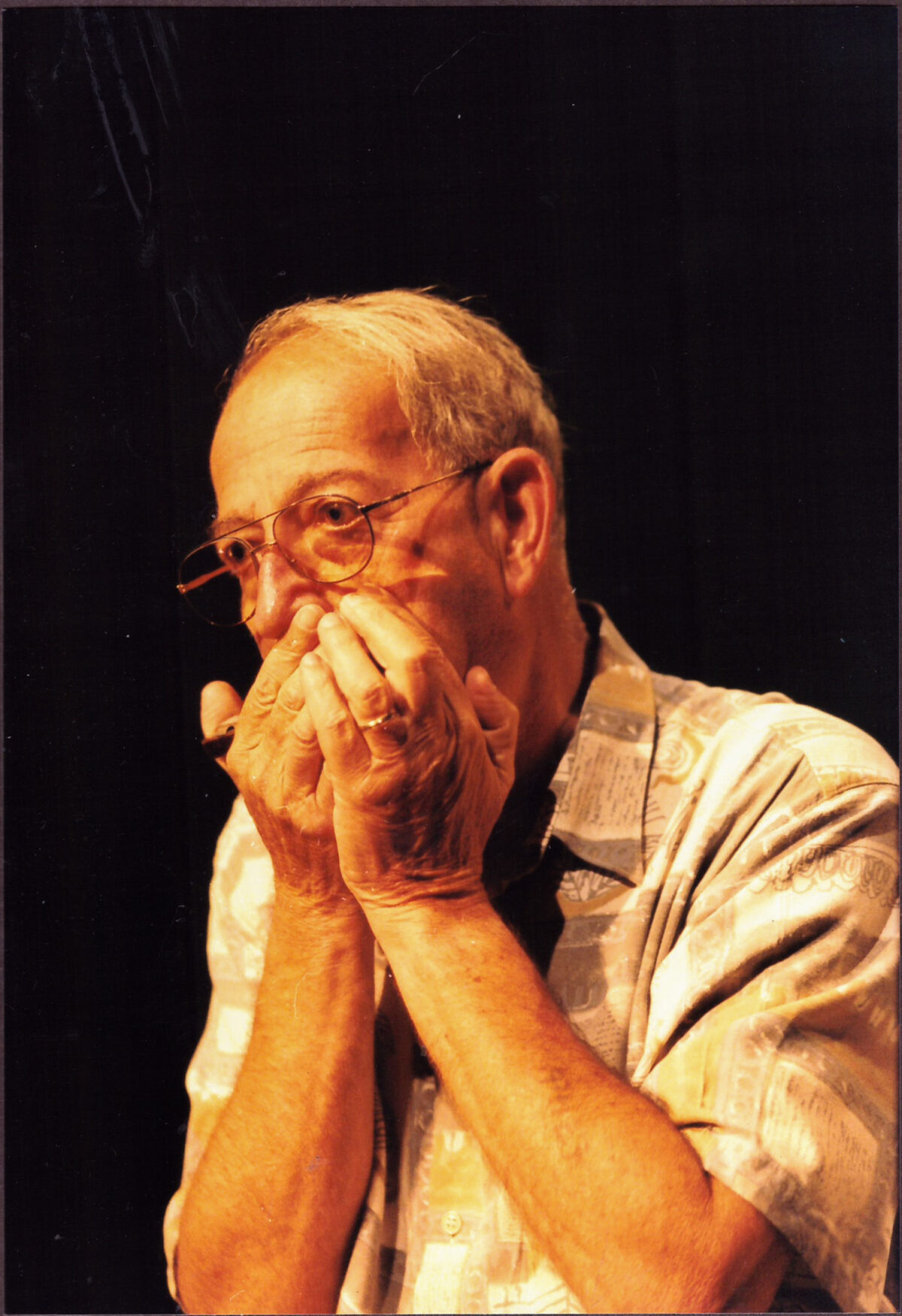

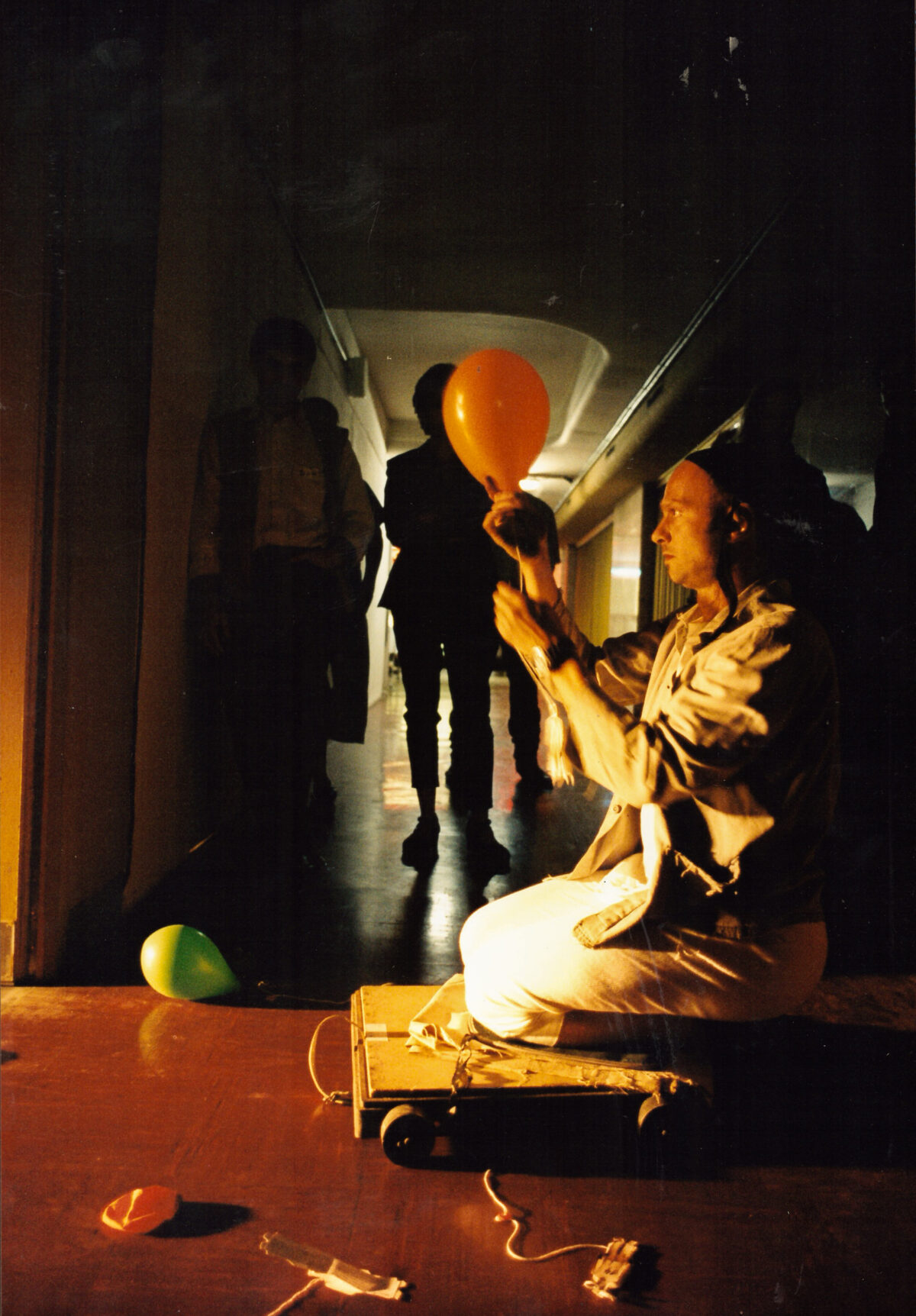

“My grandfather, Rudolf Aurel Buxbaum, was Jewish. During WWII he perished in the Lublin-Majdanek concentration camp. I was deeply and intensely preoccupied with his fate and with the Holocaust. It haunted me in my dreams. I recorded over 60 dreams in which I was either a victim or a perpetrator in a concentration camp. In one dream, I even encountered Adolf Hitler. In that dream, I was a blonde woman with a large bust and was a guest of Hitler. In performances (at the Theater am Neumarkt), I recited these dreams on stage. For each dream, I brought children’s balloons – each balloon for one dream. I opened the balloons to inhale the helium. The dreams then came out of me in a Mickey Mouse voice. It was both humorous and terrifying, as the lack of oxygen caused balance issues. On one occasion, I even collapsed on stage.”

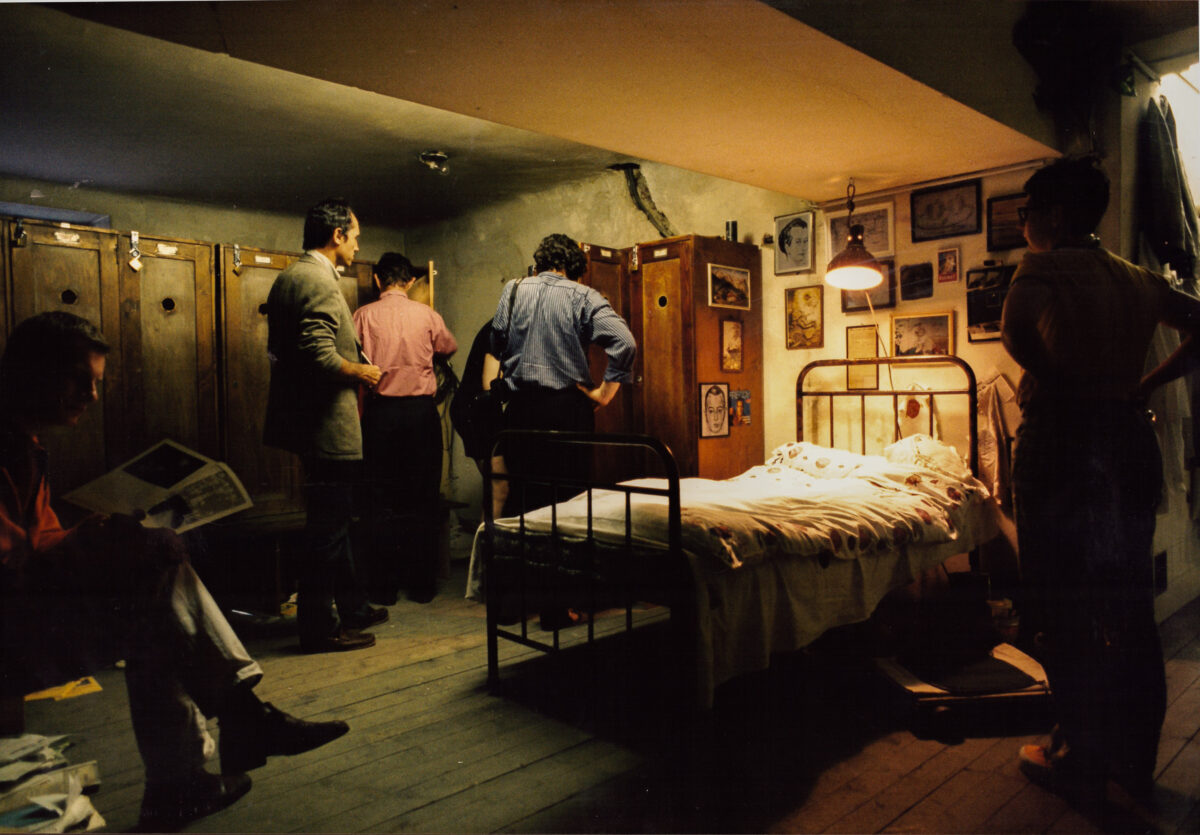

Following these performances, Buxbaum was invited by Luc Bondy, Swiss Theater and Film director, to a theater festival in Vienna. The Wiener Festwochen discovered the performances, and Buxbaum was given carte blanche. He selected the former mayoral residence in the government district as the venue.

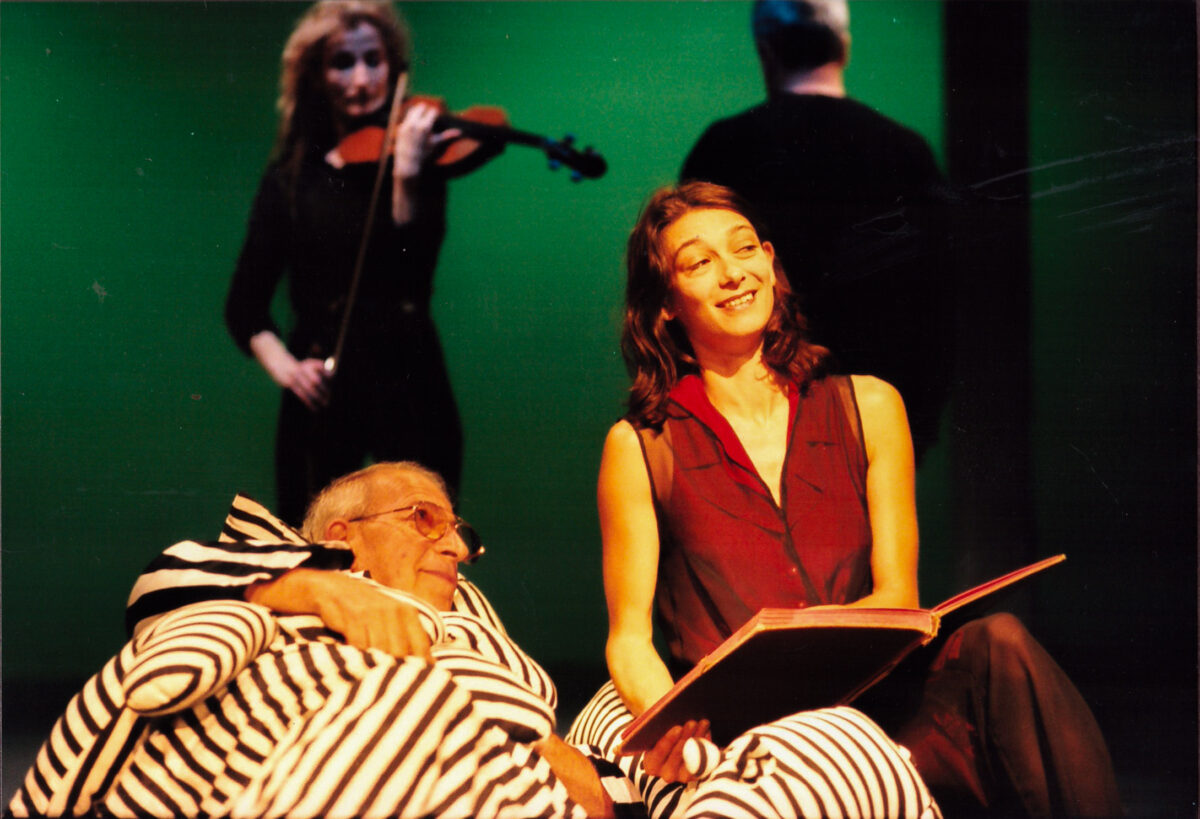

“It was vacant and before renovation. The expansive but dilapidated reception residence still carried the stale air of the post-war period, perfectly aligning with my intentions. I wanted the audience to become participants embarking on a journey back to the traumas of their own families,” describes Buxbaum. “I didn’t want theater—I wanted psychodrama. I created a site-specific, audience-interactive sequence where up to sixty participants were guided through the residence over the course of four hours. They were exposed to situations they could influence but gradually became accomplices to a higher “dramaturgy.” For the performance, I asked Richard Müller and Karel Redlich—Holocaust survivors from my family—to share their memories with the audience. At first, we disguised them as actors, dressed in striped prisoner uniforms, telling stories and setting the table. The catharsis came at the end, during the ‘banquet’, when they served soup, and the audience saw the tattooed numbers on their forearms. The elderly men in prisoner costumes were not bad actors. They were real, and their gruesome stories were true. This catharsis was crucial to breaking down the resistance among the audience that often blocks the processing of this historical past. A wave swept through the sixty guests. Tears flowed, some people even left because they couldn’t bear it. I stationed a psychologist at the exit to speak briefly with each “fugitive.” Many of those who stayed stood up and shared the tragic and humorous stories of their fathers and grandfathers in Nazi-era Vienna. We discovered that in Vienna, everyone had a story to tell. The piece was called “Was Dr. Buxbaum an Auschwitz Doctor?” All nine performances were sold out. One warm evening, I saw Georg Tabori standing in the queue. Georg Tabori! I approached him. We delayed the performance by twenty minutes. Twenty minutes on a bench in Vienna with Georg Tabori—I will never forget them.

**********

The director of Zürcher Theaterspektakel attended one of the evenings and invited me to Zurich. There, I wrote the play “Of Dogs and Humans”, which was tailored to a man called Thomas Kümmel. I met Thomas in Weimar while researching the Buchenwald concentration camp. A former East German border guard and dog handler, Kümmel switched sides after the fall of the Berlin Wall. He became a neo-Nazi and ran a dog training school in Weimar, where he bred not only attack dogs but also Weimaraners. Thomas knew everything about dogs, Weimaraners, and Buchenwald, where the SS bred Weimaraners. Thomas was a walking dog encyclopedia and extremely charismatic. “Where did you find this fantastic actor?” I was often asked. After Zurich, Thomas appeared on TV talk shows for quite some time. “Of Dogs and Humans” was another parcours that led participants through various scenarios. It started outside, where we had set up large dog cages with dogs. Thomas Kümmel was in his element, speaking about the food rations for Weimaraners in Buchenwald (three times more than the prisoners received!), about Hitler’s dog Blondi, and about the camp commandant’s wife, who had lampshades made from prisoners’ skin. After an interactive segment with the audience in the theater hall, the evening ended on a reconciliatory note with an Appenzeller dog that could hum the melody of a german song for children: „Der Mond ist aufgegangen“ (The Moon Has Risen).

********

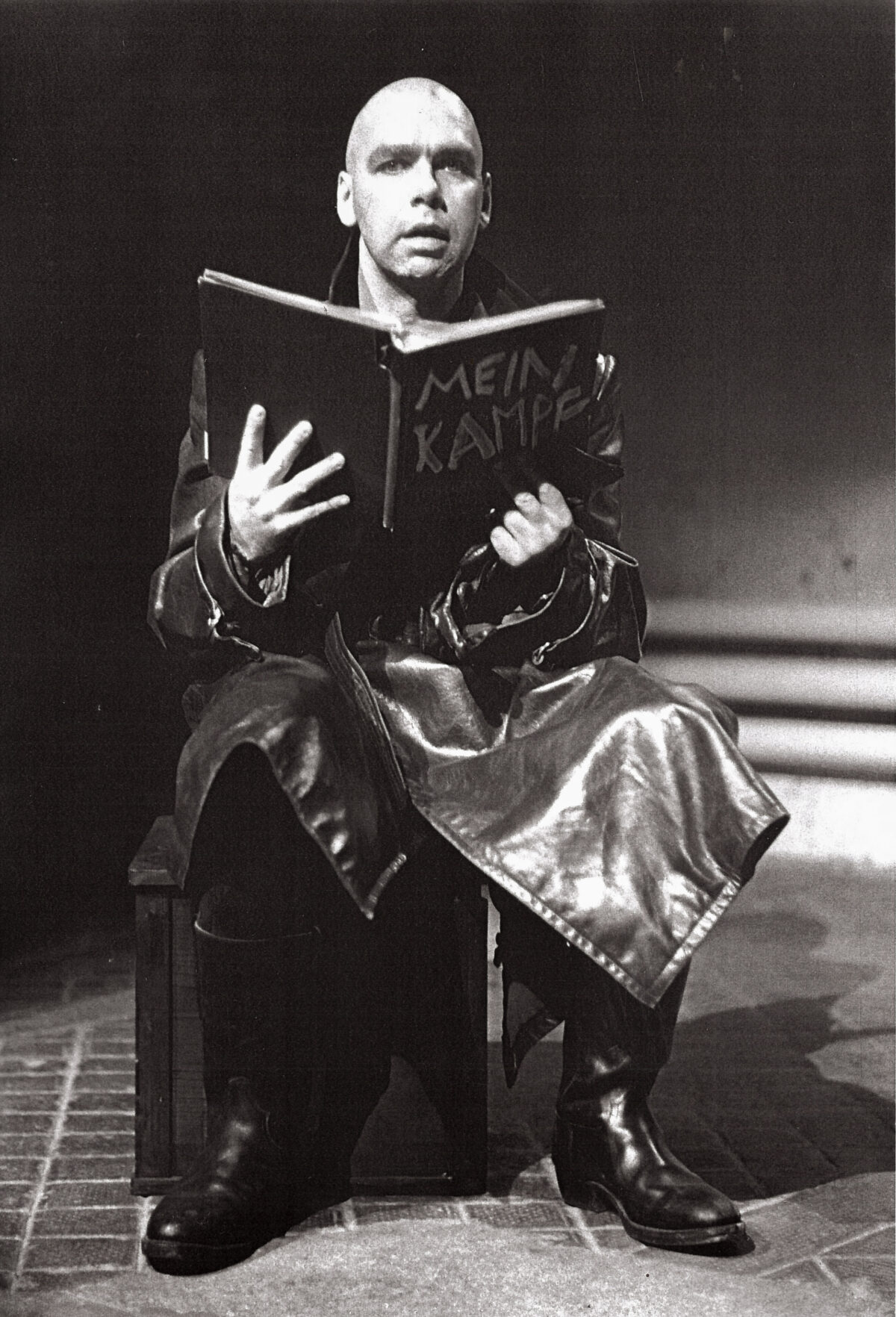

“Hitler, Redlich, Buxbaum.” was a the third play in the series about Buxbaum’s family’s traumas. It was written for the Theaterhaus Gessnerallee and with this play, Buxbaum had fully entered the world of theater: “I had a dramaturg, professional actors, lighting and sound engineers, a set designer, and a seven-figure budget – a significant undertaking for an amateur. The production was another success; Swiss President Ruth Dreifuss even attended one of the performances. However, I felt that the performative aspect, the work with the audience, and the dramatization of personal traumas were being overshadowed by theatrical spectacle. It was a participatory piece but not a profound psychodrama. I decided to hang up my theater career.” (RB, December 2024)

After the exhibition “Mein Kunst” at the Rudolfinum Gallery in Prague (1999), Buxbaum developed the theme further in a performative way. In the performance “Come with Me into Himmler’s Bed!” at the Kunstverein Oberberg in Stuttgart (1995), he read “Love Letters to Adolf Hitler.”

In other performances – this time at the Theater am Neumarkt (in Zurich, 2001), Buxbaum brought to life his haunting dreams about Holocaust when he recited them on the stage:

“My grandfather, Rudolf Aurel Buxbaum, was Jewish. During WWII he perished in the Lublin-Majdanek concentration camp. I was deeply and intensely preoccupied with his fate and with the Holocaust. It haunted me in my dreams. I recorded over 60 dreams in which I was either a victim or a perpetrator in a concentration camp. In one dream, I even encountered Adolf Hitler. In that dream, I was a blonde woman with a large bust and was a guest of Hitler. In performances (at the Theater am Neumarkt), I recited these dreams on stage. For each dream, I brought children’s balloons – each balloon for one dream. I opened the balloons to inhale the helium. The dreams then came out of me in a Mickey Mouse voice. It was both humorous and terrifying, as the lack of oxygen caused balance issues. On one occasion, I even collapsed on stage.”

Following these performances, Buxbaum was invited by Luc Bondy, Swiss Theater and Film director, to a theater festival in Vienna. The Wiener Festwochen discovered the performances, and Buxbaum was given carte blanche. He selected the former mayoral residence in the government district as the venue.

“It was vacant and before renovation. The expansive but dilapidated reception residence still carried the stale air of the post-war period, perfectly aligning with my intentions. I wanted the audience to become participants embarking on a journey back to the traumas of their own families,” describes Buxbaum. “I didn’t want theater—I wanted psychodrama. I created a site-specific, audience-interactive sequence where up to sixty participants were guided through the residence over the course of four hours. They were exposed to situations they could influence but gradually became accomplices to a higher “dramaturgy.” For the performance, I asked Richard Müller and Karel Redlich—Holocaust survivors from my family—to share their memories with the audience. At first, we disguised them as actors, dressed in striped prisoner uniforms, telling stories and setting the table. The catharsis came at the end, during the ‘banquet’, when they served soup, and the audience saw the tattooed numbers on their forearms. The elderly men in prisoner costumes were not bad actors. They were real, and their gruesome stories were true. This catharsis was crucial to breaking down the resistance among the audience that often blocks the processing of this historical past. A wave swept through the sixty guests. Tears flowed, some people even left because they couldn’t bear it. I stationed a psychologist at the exit to speak briefly with each “fugitive.” Many of those who stayed stood up and shared the tragic and humorous stories of their fathers and grandfathers in Nazi-era Vienna. We discovered that in Vienna, everyone had a story to tell. The piece was called “Was Dr. Buxbaum an Auschwitz Doctor?” All nine performances were sold out. One warm evening, I saw Georg Tabori standing in the queue. Georg Tabori! I approached him. We delayed the performance by twenty minutes. Twenty minutes on a bench in Vienna with Georg Tabori—I will never forget them.

**********

The director of Zürcher Theaterspektakel attended one of the evenings and invited me to Zurich. There, I wrote the play “Of Dogs and Humans”, which was tailored to a man called Thomas Kümmel. I met Thomas in Weimar while researching the Buchenwald concentration camp. A former East German border guard and dog handler, Kümmel switched sides after the fall of the Berlin Wall. He became a neo-Nazi and ran a dog training school in Weimar, where he bred not only attack dogs but also Weimaraners. Thomas knew everything about dogs, Weimaraners, and Buchenwald, where the SS bred Weimaraners. Thomas was a walking dog encyclopedia and extremely charismatic. “Where did you find this fantastic actor?” I was often asked. After Zurich, Thomas appeared on TV talk shows for quite some time. “Of Dogs and Humans” was another parcours that led participants through various scenarios. It started outside, where we had set up large dog cages with dogs. Thomas Kümmel was in his element, speaking about the food rations for Weimaraners in Buchenwald (three times more than the prisoners received!), about Hitler’s dog Blondi, and about the camp commandant’s wife, who had lampshades made from prisoners’ skin. After an interactive segment with the audience in the theater hall, the evening ended on a reconciliatory note with an Appenzeller dog that could hum the melody of a german song for children: „Der Mond ist aufgegangen“ (The Moon Has Risen).

********

“Hitler, Redlich, Buxbaum.” was a the third play in the series about Buxbaum’s family’s traumas. It was written for the Theaterhaus Gessnerallee and with this play, Buxbaum had fully entered the world of theater: “I had a dramaturg, professional actors, lighting and sound engineers, a set designer, and a seven-figure budget – a significant undertaking for an amateur. The production was another success; Swiss President Ruth Dreifuss even attended one of the performances. However, I felt that the performative aspect, the work with the audience, and the dramatization of personal traumas were being overshadowed by theatrical spectacle. It was a participatory piece but not a profound psychodrama. I decided to hang up my theater career.” (RB, December 2024)