Platzspitz

1991

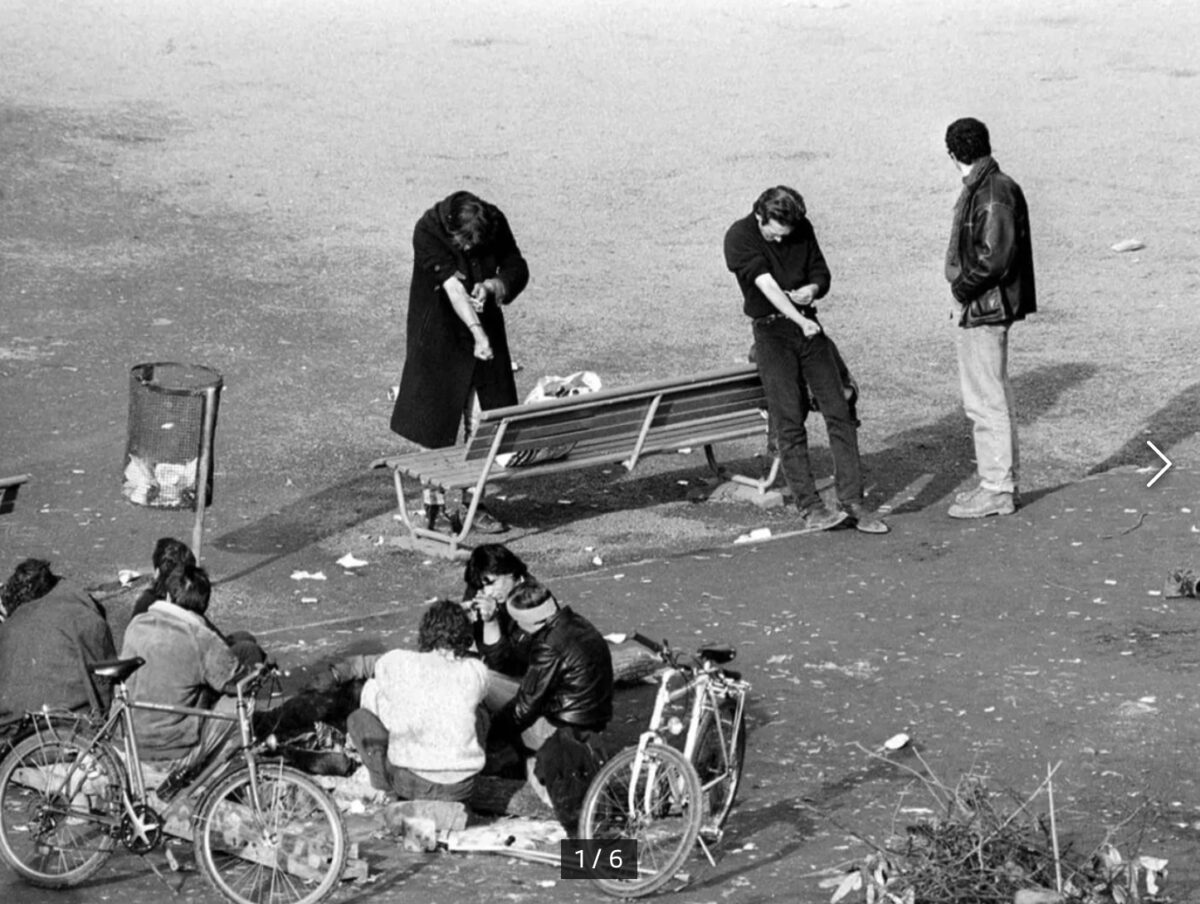

The Platzspitz is a small peninsula in the Limmat River near Zurich’s main train station. Once a tranquil park beside the Swiss National Museum, it became a notorious hub for the heroin trade and an “open drug scene” in the early 1990s. Despite covering only a few hundred square meters, it formed a striking crossroads between life and death, misery and joy, poverty and affluence, indifference and compassion—until police finally cleared the site. For months, the Platzspitz served as the “home” of hundreds of drug addicts and became a subject of national and international media attention, a symbol of the “other Switzerland.”

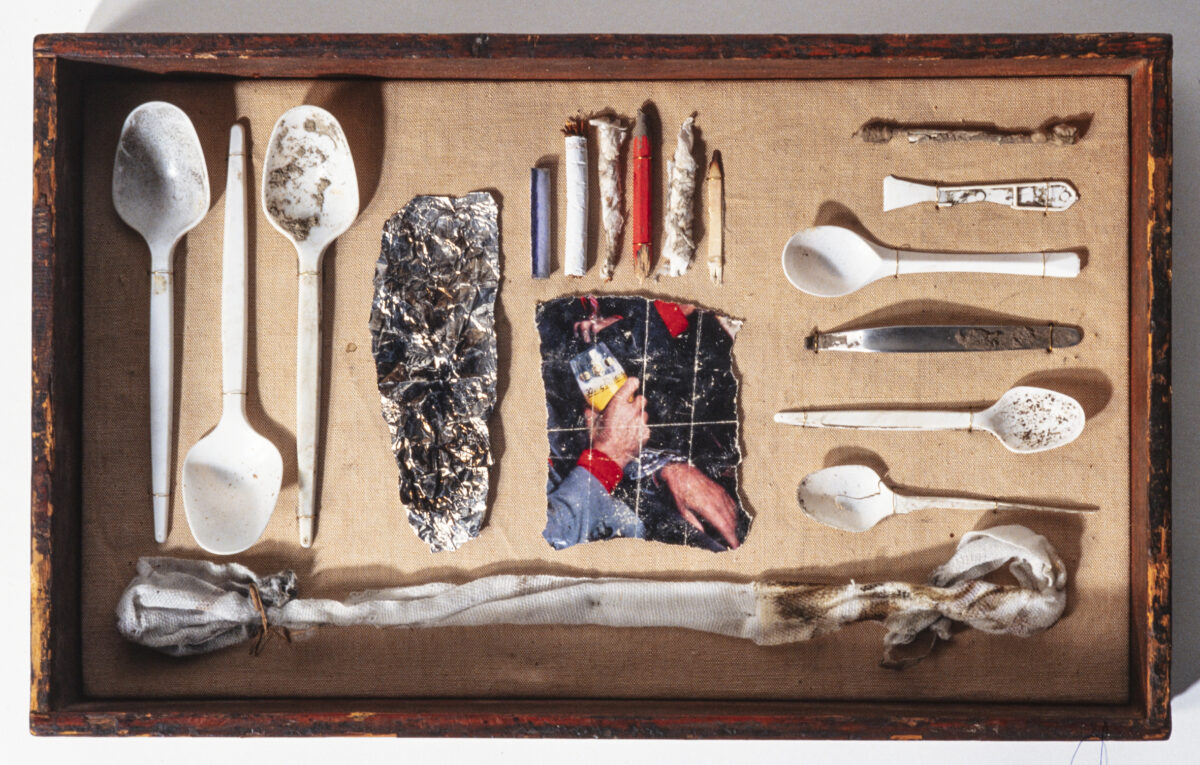

Over a period of two years, Buxbaum carried out several artistic interventions in and around the former “drug ghetto.” After the authorities shut down the Platzspitz, the addicts were abruptly deprived of their “home.” In response, Buxbaum created so-called “shooting rooms” in his exhibitions. Visitors to the Kunsthalle Wil and the Kunsthaus Oerlikon found themselves confronted with typical drug-use paraphernalia: syringes, spoons, water, ascorbic acid, and candles for heating drugs.

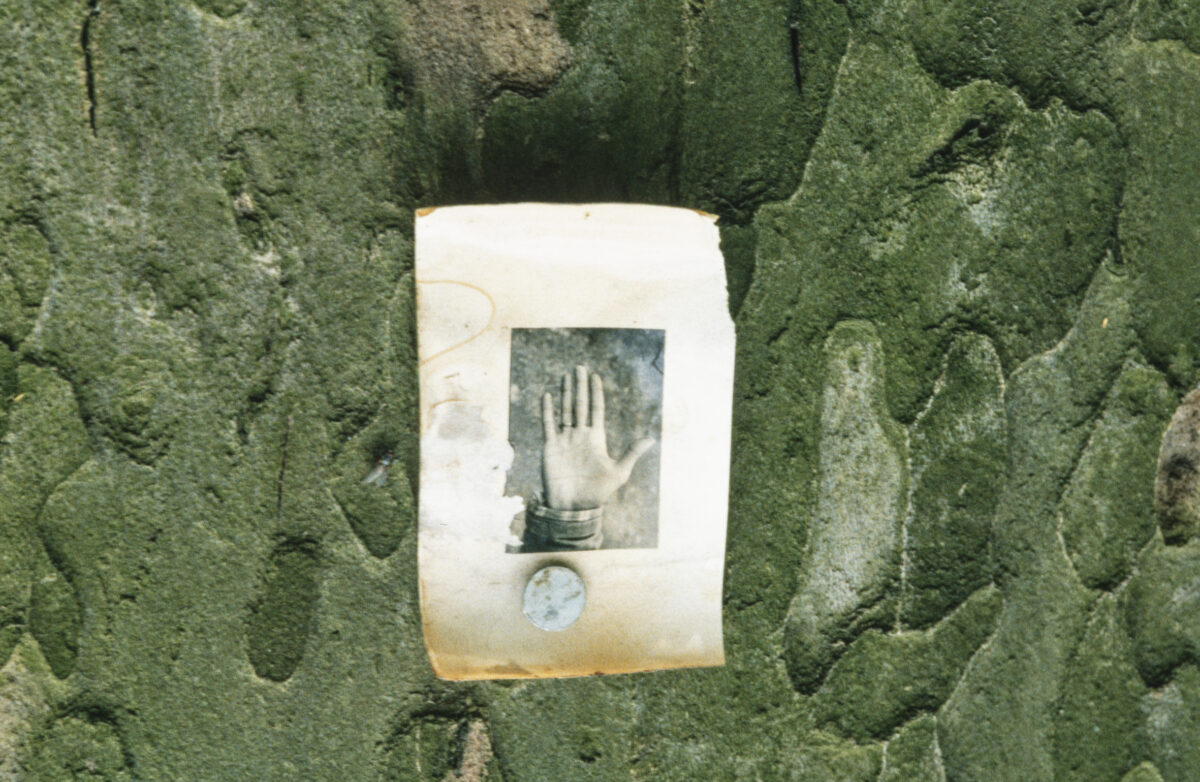

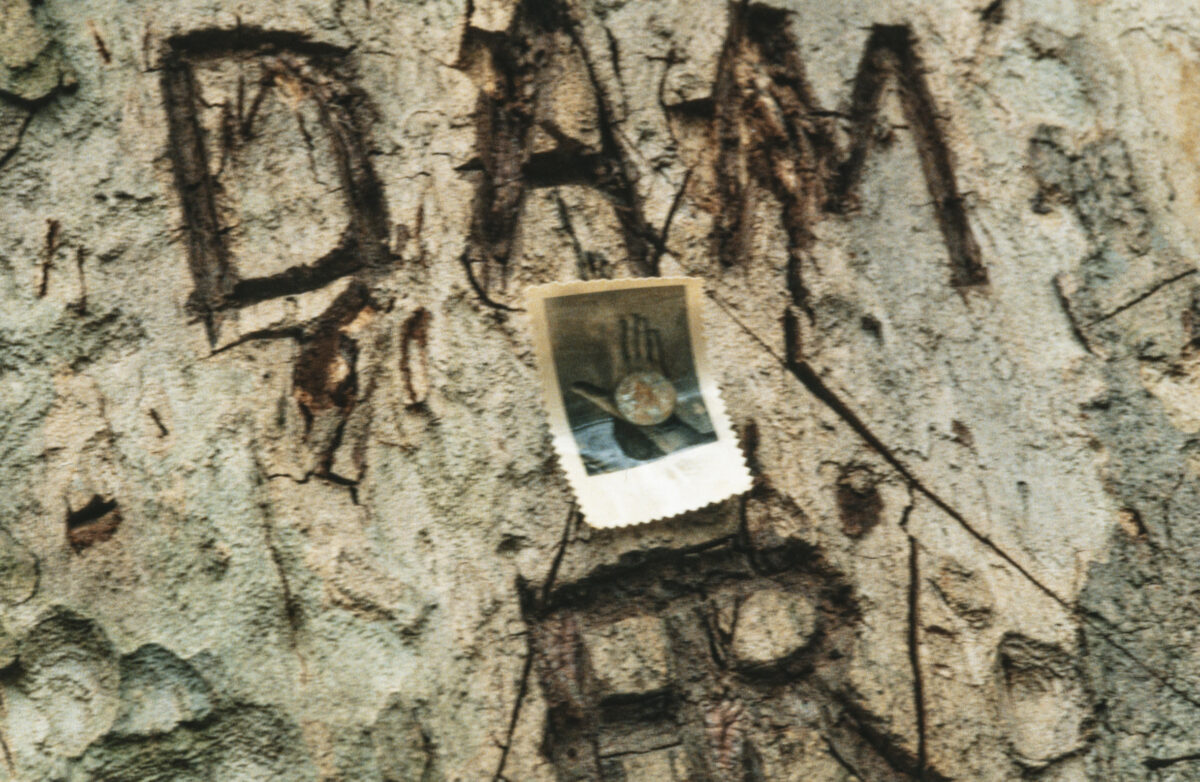

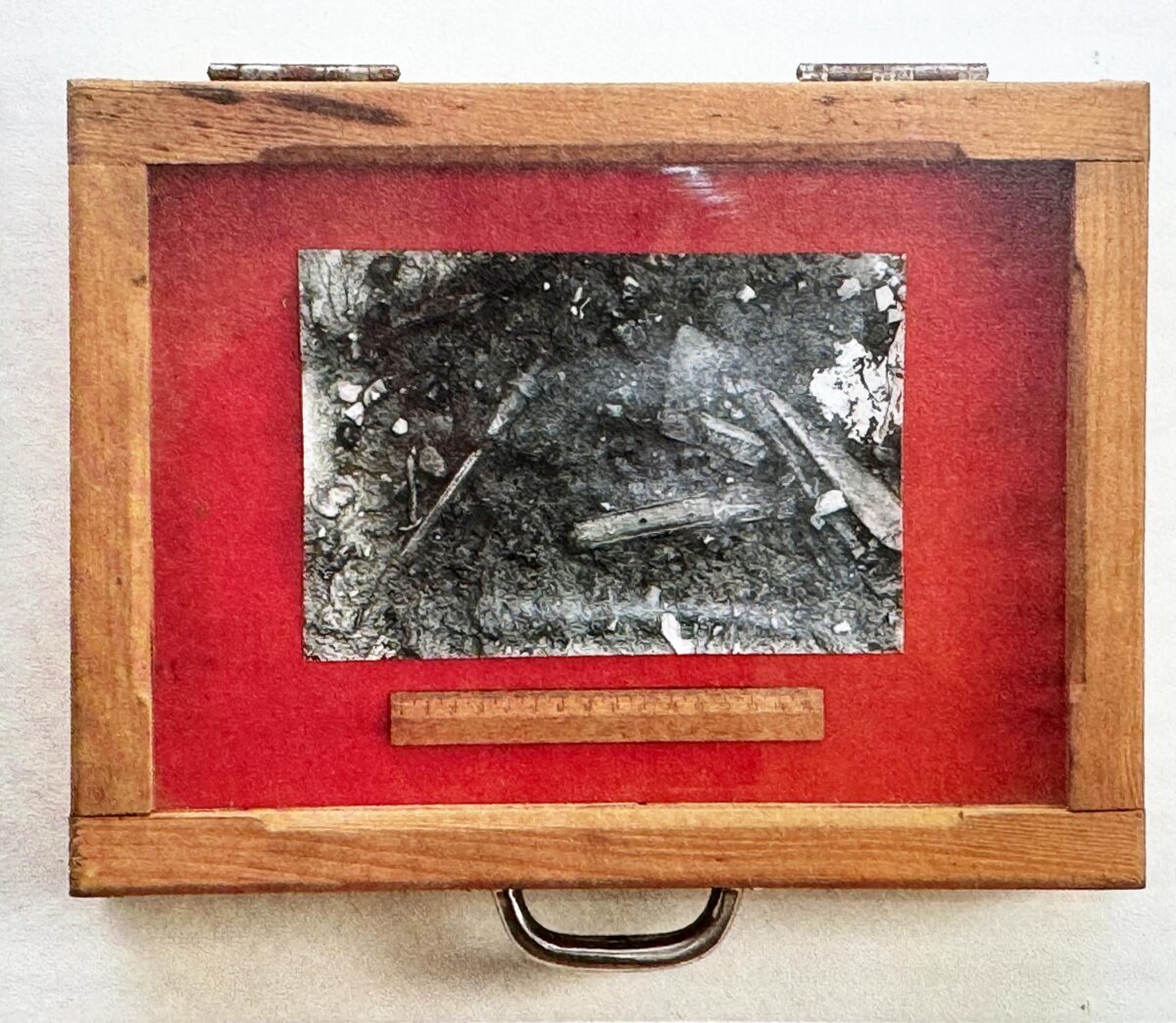

Buxbaum continued to visit the park regularly, photographing what remained of the scene. He asked addicts if he could photograph their hands, producing small, jagged-edged prints reminiscent of old family-album snapshots. These images of hands were then nailed to trees in the Platzspitz as a protest against the authorities’ refusal to provide clean syringes—even in the midst of the AIDS epidemic. Eventually, the Zurich government relented, introducing an exchange program in which addicts could receive as many sterile syringes as they returned for disposal, aiming to slow the spread of HIV/AIDS.

The new policy made used syringes valuable, and addicts began searching for them in bushes and trash bins. Buxbaum joined these searches, collecting discarded syringes, needles, and blood-stained swabs. He later arranged them in elaborate, baroque-style ornamental patterns and displayed them in glass cases.

The Platzspitz is a small peninsula in the Limmat River near Zurich’s main train station. Once a tranquil park beside the Swiss National Museum, it became a notorious hub for the heroin trade and an “open drug scene” in the early 1990s. Despite covering only a few hundred square meters, it formed a striking crossroads between life and death, misery and joy, poverty and affluence, indifference and compassion—until police finally cleared the site. For months, the Platzspitz served as the “home” of hundreds of drug addicts and became a subject of national and international media attention, a symbol of the “other Switzerland.”

Over a period of two years, Buxbaum carried out several artistic interventions in and around the former “drug ghetto.” After the authorities shut down the Platzspitz, the addicts were abruptly deprived of their “home.” In response, Buxbaum created so-called “shooting rooms” in his exhibitions. Visitors to the Kunsthalle Wil and the Kunsthaus Oerlikon found themselves confronted with typical drug-use paraphernalia: syringes, spoons, water, ascorbic acid, and candles for heating drugs.

Buxbaum continued to visit the park regularly, photographing what remained of the scene. He asked addicts if he could photograph their hands, producing small, jagged-edged prints reminiscent of old family-album snapshots. These images of hands were then nailed to trees in the Platzspitz as a protest against the authorities’ refusal to provide clean syringes—even in the midst of the AIDS epidemic. Eventually, the Zurich government relented, introducing an exchange program in which addicts could receive as many sterile syringes as they returned for disposal, aiming to slow the spread of HIV/AIDS.

The new policy made used syringes valuable, and addicts began searching for them in bushes and trash bins. Buxbaum joined these searches, collecting discarded syringes, needles, and blood-stained swabs. He later arranged them in elaborate, baroque-style ornamental patterns and displayed them in glass cases.