Souvenirs (Memories)

2015

Souvenirs (Memories): A conversation between the psychiatrist Dr. R. Buxbaum and Artist Roman Buxbaum

Psychiatrist: In your installation “Souvenirs” in Karlštejn you process memories of your recently deceased mother. The French sociologist Maurice Halbwachs, who died in the Buchenwald concentration camp in 1945, said that what we remember has more to do with our current ideas than with what was. What is memory for you?

Artist: Memory is a psychological process that takes place in the present and concerns the past. It is an ever-changing retrospective, an inner narrative – a “remembering”. I have an ongoing conversation with myself about my own past, about something that no longer exists. Of course I existed in the past. But I was different than I am today. As an individual, however, I need a temporal continuity that perhaps doesn’t even exist. I have to constantly recreate this fiction that we call memory.

Psychiatrist: Isn’t there an identity without the past – in the here and now? That’s what Buddhists strive for and what dementia patients experience.

Artist: We normal people feel pretty much lost without our biography. Anchoring ourselves in our own life story enables us to believe in our future, gives us hope and vision. That’s why the photos we constantly take are so important. We photograph everything in the knowledge that it will soon no longer be there. The photo “captures” what is already disappearing. And the memory is then constructed around these small puzzle pieces.

Psychiatrist: You are only marginally remembered in the art world as a visual artist, although you were one of the “young talents” of the Zurich and Prague scene in the 80s and 90s. You had several well-received solo exhibitions back then and were awarded grants. Then you disappeared as an artist. What happened?

Artist: In the art world, I am now known primarily as the person who discovered the Czech photographer Miroslav Tichý. When I initiated Tichý’s coming out together with Harald Szeemann in 2004, I decided to go into hiding with my own work and become a “retired artist” and retire.

Psychiatrist: And after 10 years, you’re coming back from artistic retirement and want to be an artist again?

Artist: I absolutely had to do this one work. Our mother died. Shortly before that, we had a painful separation from our wife. These two losses have thrown me into a crisis, at least, and I’m trying to find my way. I started working more intensively as an artist again. That’s probably the most intense inner dialogue I’m capable of.

Psychiatrist: I have to admit that even as a psychiatrist, I think I’ve exhausted all treatment options. Talking to friends helps, but the most important thing is a dialogue with myself. This interview is also part of that.

Artist: I thought only crazy people talked to themselves?

Psychiatrist: Be careful what you say! If you call me crazy, then it’s a swear word. If I call you that, then it’s a diagnosis! But back to your work of art. Your installation “Souvenirs” is not taking place at an art venue, but in a souvenir shop on the main road to the Czech Republic’s most famous castle, Karlštejn, in the Czech Republic. Why there?

Artist: The place is the message, or part of it. Our mother left us a house in Karlštejn. She was born there and died there. She died in the kitchen, in exactly the same place, under the same window where we were supposedly conceived. The house also has a souvenir shop. Almost half a million people have to walk up this path to the castle every year. After Prague’s Old Town, Karlštejn is a must for package holidaymakers. On beautiful summer days, a constant stream of people walk past Mother Buxbaum’s kiosks. Grandparents used to sell postcards, ice cream and souvenirs here. When Grandfather died 18 years ago, I made artistic arrangements of the remaining postcards from before the Second World War.

Psychiatrist: Back to you. What fascinates you so much about ancestors? This focus on the past seems a bit whiny to me.

Artist: I’m tearful. I’m also the only one who knows the history of the objects in my mother’s house. Usually you throw away the furniture and clothes when someone dies. And in doing so, you throw away part of the burden of memories. However, I want to keep as long a connection to my ancestors as possible and try to push as much of the past into the future as possible. This may be due to a certain uprooting. Our whole family has been scattered to the four winds because of the exile and I have to create my own connections. For me, my ancestors are a connection that anchors me in time and gives me a where and where I’m going, a position and an orientation. We buried our grandfather in the same grave as his daughter and our mother tomorrow.

Psychiatrist: You’ve worked on this topic before. As in the 80s and 90s, you processed personal and collective trauma in a similar way. After your grandmother died, you made installations from the objects your father’s ancestors had found in the house in Kyjov.

Artist: Yes, it was actually the same as it is now. 20 years ago. At the time, I built a hut in the Aarau art space from the objects I had inherited from my grandmother’s attic. It was winter. The art space was only heated by a stove. We built the hut around the stove. It was nice and warm and we sat on my grandmother’s chairs and drank the last of the Slivovitz that she had distilled. After the exhibition ended, I took the ancestral hut apart and made a completely different installation in the Centre Pasquart in Biel from the same material. That was my largest solo exhibition. It covered seven rooms. In one of the museum rooms, I sawed up the furniture and branded it with a branding iron with the inscription “Art makes you free”. Ancestral rubbish became art objects. Of course, the inscription also alludes to my grandfather, who was killed in the Majdanek concentration camp in 1942 and whose belongings I found in the attic. That was the beginning of my engagement with the Holocaust in exhibitions, performances and plays. After the exhibition in the Pasquart Centre, the ancestral waste was returned to the Czech Republic and was exhibited in the Na Bydýlku gallery in Brno in 1992. I made a shelf in the middle of the room, which I packed so full that it was like a wall. The back part of the exhibition room was visible between the memorabilia but not accessible – just like the past.

Psychiatrist: How did the installation in the souvenir shop come about? Artist: This is a farewell to our mother and her ancestors – and also to myself, at least in my identity as a son, grandson and great-grandson. I chose a few objects from four generations. It is a chair belonging to my grandmother that was missing its seat, an ugly, chrome-plated frame of a small table belonging to my mother that was missing its glass top, my mother’s sneakers that she had not been able to wear for 20 years and an empty picture frame. In it was an oil painting that I had painted and that I gave to my mother as a teenager. On a display rack that was already in the souvenir shop (forgotten by the last tenant there) I hung coat hangers from the discarded clothes of the dead from three generations. All of these things are somehow incomplete, incomplete or empty. Just like memories. At first glance everything seems unspectacular and forgotten. At second glance, some of the passers-by might see that everything is floating five centimeters above the ground. Psychiatrist: The installation is called Souvenirs. What are souvenirs?

Artist: Souvenirs – memories in French – are small, useless kitsch objects that you buy to anchor a moment in the flow of life and make it unforgettable. Kitsch is an aesthetic lie. And lies can kill. Kitsch kills. The self-construction of our past and our self can be kitschy and distorted and can cover up many ugly things from the past.

Psychiatrist: You say we use memory to reinvent ourselves again and again?

Artist: I constantly have to fill in gaps in my memory. When memories are lost, a piece of life is lost. In exile, you tend to draw a line under it and forget everything in your country of origin. You then have to work through it again later. Then there is the traumatic history of my Jewish ancestors. I had to work through that too. I did that with artistic means, in exhibitions, performances and on the theater stage.

Psychiatrist: Are you an artist again now?

Artist: And the crazy thing is that the guest bed used to be in exactly that spot, under that window in the kitchen. And we were conceived in that guest bed on a hot summer evening. She fell down and tried to get up using the heater under the window, but couldn’t. We cleaned up our mother’s blood and feces in the kitchen. That’s where she died. On the spot where we were created.

Psychiatrist: It must have been a weekend at the end of July 1955. Our newly married parents were visiting our in-laws. They were happy at the time. There are beautiful photos from that time of the two young people in love. The best time of their lives. And 68 years later, our mother breathed her last in exactly the same place where she received our life – not even a step away from the cradle to the grave.

Artist: I think it’s really crap, all this coming and going, falling in love and losing each other. Wouldn’t it be best not to have been born at all?

Psychiatrist: Somehow everything goes in circles. But the worst thing for me was choosing the dress for the coffin. Rummaging through those closets and seeing all the clothes we knew again.

Artist: Yes, that was bad. She didn’t throw anything away. There were cute old blouses from the 70s, nicely cleaned and ironed and hung up in plastic wrap, as if for eternity. We remembered every pair of trousers, every sweater. She wore them when we were young! And we had to dig through them and put most of them in bags for the clothing collection. I kept a pair of nice old clothes for Anna.

Psychiatrist: Or the sneakers that you then used for the installation. She traveled all over America in the 90s with the sneakers.

Artist: She hadn’t been able to put on her sneakers for 20 years. She got these terrible leg edemas. Her feet were like elephant legs. She could hardly wear shoes anymore. But she didn’t throw away the old shoes. Do you know what I regret most? I never wanted to touch her sick feet. I never stroked them. I felt a resistance, a kind of disgust. Maybe it was the fear of the illness and of growing old. We should have stroked those poor, tormented, ugly, black elephant legs. We should have rubbed ointment on them. We can never make up for what we missed. I would do things differently today.

Psychiatrist: That’s true, we would definitely do that today. But you know how difficult she was. Visiting her was always a drama.

Artist: Her stubbornness, her autism, her increasing dementia, which made it so difficult for everyone to like her. The people around her kept fleeing. She could be so unbearable.

Psychiatrist: She was very difficult. Her body was destroyed and her psyche broken. Life didn’t spare her.

Artist: And the dementia, you somehow missed that, dear doctor.

Psychiatrist: That’s right, I missed it, the dementia. But maybe that’s better that way. She was able to stay at home. And now I’m going to tell you something that you won’t understand. The moment she died, I felt all the bad things disappear – like her bad legs, which we will carry to the grave. The difficult things that covered up all the good things were gone, like leaves in autumn that the rain washes away. I suddenly saw mother with different eyes. Her good sides were back. The kind-hearted, content, humorous, loyal, honest and loving mother that we have long since forgotten.

Artist: You’re kidding yourself. The difficult thing about her disappeared because she was dead. And dead people are not difficult.

Psychiatrist: All of life is difficult. But the moment she died, when we entered her house, it became very clear to me: she is back, as she once was. The person she once was, the pretty, intelligent girl with a heart of gold.

Artist: You remain a romantic, a religious fanatic. If you didn’t hold back, the Assumption of Mary would come now. You know that I have a hard time with so much transcendence. You are pretty much after our mother.

Psychiatrist: And after our father, you are more of a melancholic, always Janus-faced, one eye looking back, observing the present from the past.

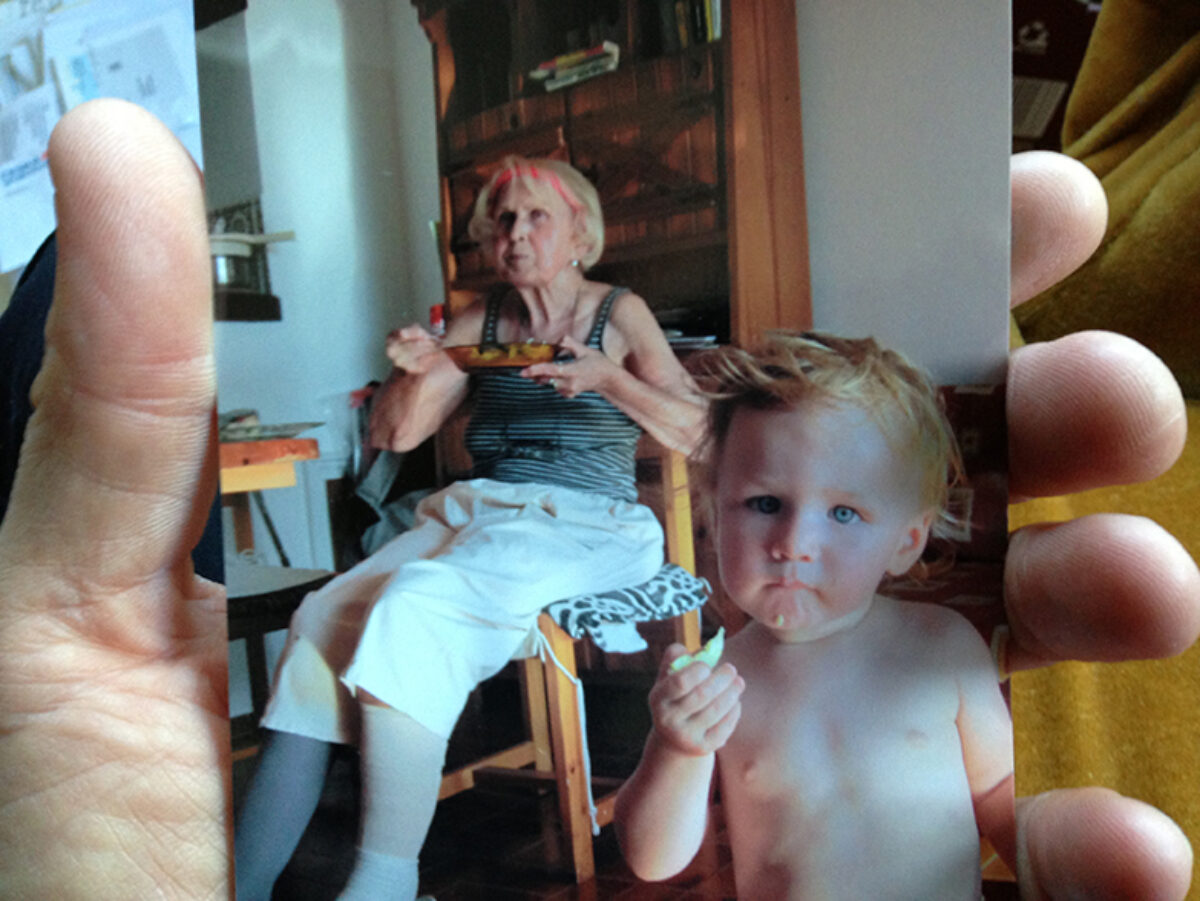

Artist: The past is very important to me. All the many cardboard boxes in my mother’s house are filled with the past. Memories of three or four generations. Everything carefully organized and packed. Grandmother’s prayer book, mother’s golden curls that were cut off as a child and wrapped in a piece of paper, grandfather’s self-sewn national flag from 1945, our milk teeth and all the many photographs, right down to the photos of our daughter Anna. Our lives carefully collected as our mother’s inheritance. Is that what remains, the memories?

Psychiatrist: The memories and the wine. Do you remember the story about the wedding wine?

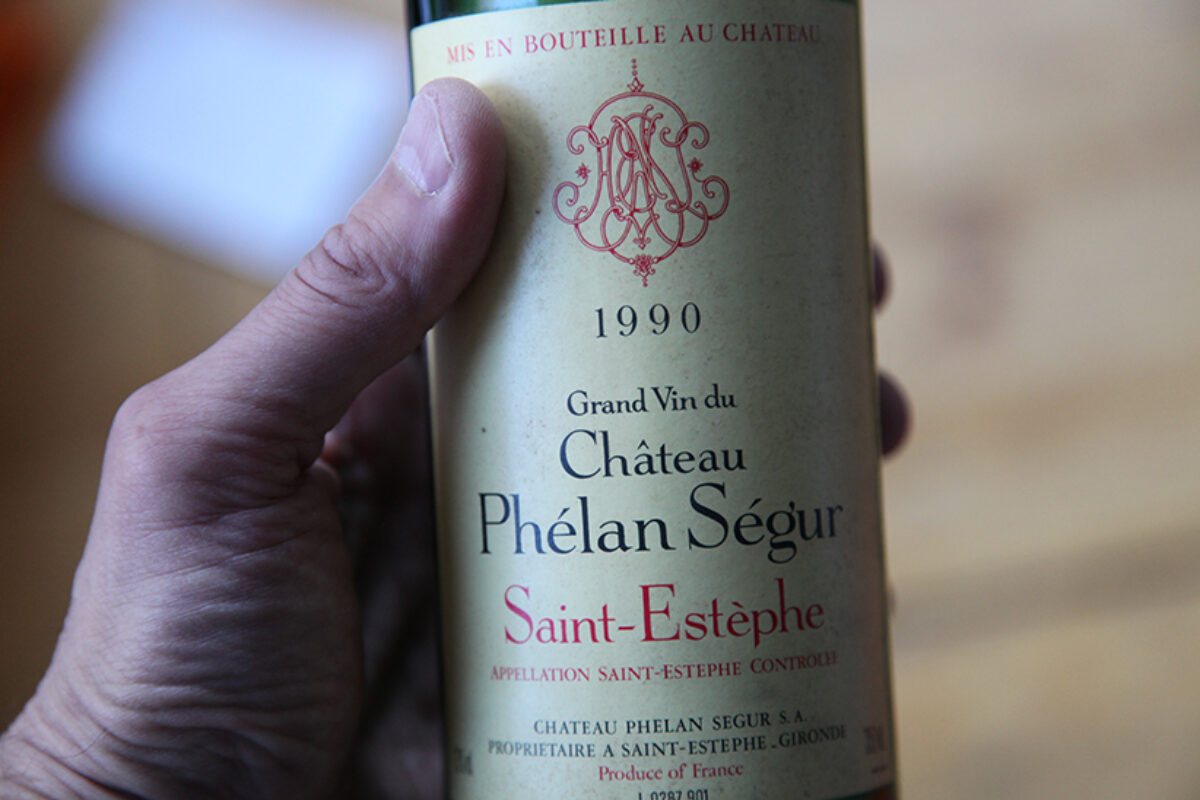

Artist: Pure horror. Typical mother. When we were 34, our mother bought the wedding wine for us on one of her tasting trips to France. A case of Chateau Phélan Ségur, Saint–Estéphe, vintage 1990. She spent 1000 francs on it. Without asking us. The wine box was moved with us for decades and was in all the cellars of the apartments where mother had lived. Not very good storage. No wonder that when the time finally came 16 years later and we got married, there was no more to be expected from this wine. But mother insisted that her wedding wine be served at the wedding. A couple of bottles were opened and it was worse than feared. Undrinkable. All the bottles had corks, some had mutated into a kind of port wine, or even vinegar.

Psychiatrist: But mother could not be convinced of that. She started an argument with those guests who did not want to drink the wine. For them, her wedding wine was delicious. Other guests who drank the wine out of ignorance or indifference were warned not to drink too much of it because the wine was so precious.

Artist: The wedding wine. After the wedding, we put the box with the last bottles that no one wanted to open because the wine was spoiled. back in the cellar. It is still there. Now, after her death, we wanted to honor Mother. We lit candles, put up photos of her and we took a bottle of wedding wine out of the box and opened it. Psychiatrist: And what a surprise! It was the best St. Emillion we have ever tasted. It was perhaps the only bottle that had not spoiled, but had matured over 30 years to become the best Burgundy. What an aroma, what a lovely scent. What a dignified, round taste! Artist: We were amazed. It was an enlightenment. The best wine last. Like in Canaan. Mother smiles at us again from heaven above: “Now you rascals see how right I was! The wine is heavenly!”

Psychiatrist: The main thing is that we still laugh! And she always laughed! That’s why we’re doing it in a really Catholic way today. Even though we’re quarter Jewish. We have already buried her father and we will lay our mother in the same grave. We will try to organize a mass and a good singer. And we will lay her in an open coffin. Can you think of anything else? Have we forgotten something?

Artist: No. We have said the most important thing. Let’s go and bury our funny mother.

Souvenirs (Memories): A conversation between the psychiatrist Dr. R. Buxbaum and Artist Roman Buxbaum

Psychiatrist: In your installation “Souvenirs” in Karlštejn you process memories of your recently deceased mother. The French sociologist Maurice Halbwachs, who died in the Buchenwald concentration camp in 1945, said that what we remember has more to do with our current ideas than with what was. What is memory for you?

Artist: Memory is a psychological process that takes place in the present and concerns the past. It is an ever-changing retrospective, an inner narrative – a “remembering”. I have an ongoing conversation with myself about my own past, about something that no longer exists. Of course I existed in the past. But I was different than I am today. As an individual, however, I need a temporal continuity that perhaps doesn’t even exist. I have to constantly recreate this fiction that we call memory.

Psychiatrist: Isn’t there an identity without the past – in the here and now? That’s what Buddhists strive for and what dementia patients experience.

Artist: We normal people feel pretty much lost without our biography. Anchoring ourselves in our own life story enables us to believe in our future, gives us hope and vision. That’s why the photos we constantly take are so important. We photograph everything in the knowledge that it will soon no longer be there. The photo “captures” what is already disappearing. And the memory is then constructed around these small puzzle pieces.

Psychiatrist: You are only marginally remembered in the art world as a visual artist, although you were one of the “young talents” of the Zurich and Prague scene in the 80s and 90s. You had several well-received solo exhibitions back then and were awarded grants. Then you disappeared as an artist. What happened?

Artist: In the art world, I am now known primarily as the person who discovered the Czech photographer Miroslav Tichý. When I initiated Tichý’s coming out together with Harald Szeemann in 2004, I decided to go into hiding with my own work and become a “retired artist” and retire.

Psychiatrist: And after 10 years, you’re coming back from artistic retirement and want to be an artist again?

Artist: I absolutely had to do this one work. Our mother died. Shortly before that, we had a painful separation from our wife. These two losses have thrown me into a crisis, at least, and I’m trying to find my way. I started working more intensively as an artist again. That’s probably the most intense inner dialogue I’m capable of.

Psychiatrist: I have to admit that even as a psychiatrist, I think I’ve exhausted all treatment options. Talking to friends helps, but the most important thing is a dialogue with myself. This interview is also part of that.

Artist: I thought only crazy people talked to themselves?

Psychiatrist: Be careful what you say! If you call me crazy, then it’s a swear word. If I call you that, then it’s a diagnosis! But back to your work of art. Your installation “Souvenirs” is not taking place at an art venue, but in a souvenir shop on the main road to the Czech Republic’s most famous castle, Karlštejn, in the Czech Republic. Why there?

Artist: The place is the message, or part of it. Our mother left us a house in Karlštejn. She was born there and died there. She died in the kitchen, in exactly the same place, under the same window where we were supposedly conceived. The house also has a souvenir shop. Almost half a million people have to walk up this path to the castle every year. After Prague’s Old Town, Karlštejn is a must for package holidaymakers. On beautiful summer days, a constant stream of people walk past Mother Buxbaum’s kiosks. Grandparents used to sell postcards, ice cream and souvenirs here. When Grandfather died 18 years ago, I made artistic arrangements of the remaining postcards from before the Second World War.

Psychiatrist: Back to you. What fascinates you so much about ancestors? This focus on the past seems a bit whiny to me.

Artist: I’m tearful. I’m also the only one who knows the history of the objects in my mother’s house. Usually you throw away the furniture and clothes when someone dies. And in doing so, you throw away part of the burden of memories. However, I want to keep as long a connection to my ancestors as possible and try to push as much of the past into the future as possible. This may be due to a certain uprooting. Our whole family has been scattered to the four winds because of the exile and I have to create my own connections. For me, my ancestors are a connection that anchors me in time and gives me a where and where I’m going, a position and an orientation. We buried our grandfather in the same grave as his daughter and our mother tomorrow.

Psychiatrist: You’ve worked on this topic before. As in the 80s and 90s, you processed personal and collective trauma in a similar way. After your grandmother died, you made installations from the objects your father’s ancestors had found in the house in Kyjov.

Artist: Yes, it was actually the same as it is now. 20 years ago. At the time, I built a hut in the Aarau art space from the objects I had inherited from my grandmother’s attic. It was winter. The art space was only heated by a stove. We built the hut around the stove. It was nice and warm and we sat on my grandmother’s chairs and drank the last of the Slivovitz that she had distilled. After the exhibition ended, I took the ancestral hut apart and made a completely different installation in the Centre Pasquart in Biel from the same material. That was my largest solo exhibition. It covered seven rooms. In one of the museum rooms, I sawed up the furniture and branded it with a branding iron with the inscription “Art makes you free”. Ancestral rubbish became art objects. Of course, the inscription also alludes to my grandfather, who was killed in the Majdanek concentration camp in 1942 and whose belongings I found in the attic. That was the beginning of my engagement with the Holocaust in exhibitions, performances and plays. After the exhibition in the Pasquart Centre, the ancestral waste was returned to the Czech Republic and was exhibited in the Na Bydýlku gallery in Brno in 1992. I made a shelf in the middle of the room, which I packed so full that it was like a wall. The back part of the exhibition room was visible between the memorabilia but not accessible – just like the past.

Psychiatrist: How did the installation in the souvenir shop come about? Artist: This is a farewell to our mother and her ancestors – and also to myself, at least in my identity as a son, grandson and great-grandson. I chose a few objects from four generations. It is a chair belonging to my grandmother that was missing its seat, an ugly, chrome-plated frame of a small table belonging to my mother that was missing its glass top, my mother’s sneakers that she had not been able to wear for 20 years and an empty picture frame. In it was an oil painting that I had painted and that I gave to my mother as a teenager. On a display rack that was already in the souvenir shop (forgotten by the last tenant there) I hung coat hangers from the discarded clothes of the dead from three generations. All of these things are somehow incomplete, incomplete or empty. Just like memories. At first glance everything seems unspectacular and forgotten. At second glance, some of the passers-by might see that everything is floating five centimeters above the ground. Psychiatrist: The installation is called Souvenirs. What are souvenirs?

Artist: Souvenirs – memories in French – are small, useless kitsch objects that you buy to anchor a moment in the flow of life and make it unforgettable. Kitsch is an aesthetic lie. And lies can kill. Kitsch kills. The self-construction of our past and our self can be kitschy and distorted and can cover up many ugly things from the past.

Psychiatrist: You say we use memory to reinvent ourselves again and again?

Artist: I constantly have to fill in gaps in my memory. When memories are lost, a piece of life is lost. In exile, you tend to draw a line under it and forget everything in your country of origin. You then have to work through it again later. Then there is the traumatic history of my Jewish ancestors. I had to work through that too. I did that with artistic means, in exhibitions, performances and on the theater stage.

Psychiatrist: Are you an artist again now?

Artist: And the crazy thing is that the guest bed used to be in exactly that spot, under that window in the kitchen. And we were conceived in that guest bed on a hot summer evening. She fell down and tried to get up using the heater under the window, but couldn’t. We cleaned up our mother’s blood and feces in the kitchen. That’s where she died. On the spot where we were created.

Psychiatrist: It must have been a weekend at the end of July 1955. Our newly married parents were visiting our in-laws. They were happy at the time. There are beautiful photos from that time of the two young people in love. The best time of their lives. And 68 years later, our mother breathed her last in exactly the same place where she received our life – not even a step away from the cradle to the grave.

Artist: I think it’s really crap, all this coming and going, falling in love and losing each other. Wouldn’t it be best not to have been born at all?

Psychiatrist: Somehow everything goes in circles. But the worst thing for me was choosing the dress for the coffin. Rummaging through those closets and seeing all the clothes we knew again.

Artist: Yes, that was bad. She didn’t throw anything away. There were cute old blouses from the 70s, nicely cleaned and ironed and hung up in plastic wrap, as if for eternity. We remembered every pair of trousers, every sweater. She wore them when we were young! And we had to dig through them and put most of them in bags for the clothing collection. I kept a pair of nice old clothes for Anna.

Psychiatrist: Or the sneakers that you then used for the installation. She traveled all over America in the 90s with the sneakers.

Artist: She hadn’t been able to put on her sneakers for 20 years. She got these terrible leg edemas. Her feet were like elephant legs. She could hardly wear shoes anymore. But she didn’t throw away the old shoes. Do you know what I regret most? I never wanted to touch her sick feet. I never stroked them. I felt a resistance, a kind of disgust. Maybe it was the fear of the illness and of growing old. We should have stroked those poor, tormented, ugly, black elephant legs. We should have rubbed ointment on them. We can never make up for what we missed. I would do things differently today.

Psychiatrist: That’s true, we would definitely do that today. But you know how difficult she was. Visiting her was always a drama.

Artist: Her stubbornness, her autism, her increasing dementia, which made it so difficult for everyone to like her. The people around her kept fleeing. She could be so unbearable.

Psychiatrist: She was very difficult. Her body was destroyed and her psyche broken. Life didn’t spare her.

Artist: And the dementia, you somehow missed that, dear doctor.

Psychiatrist: That’s right, I missed it, the dementia. But maybe that’s better that way. She was able to stay at home. And now I’m going to tell you something that you won’t understand. The moment she died, I felt all the bad things disappear – like her bad legs, which we will carry to the grave. The difficult things that covered up all the good things were gone, like leaves in autumn that the rain washes away. I suddenly saw mother with different eyes. Her good sides were back. The kind-hearted, content, humorous, loyal, honest and loving mother that we have long since forgotten.

Artist: You’re kidding yourself. The difficult thing about her disappeared because she was dead. And dead people are not difficult.

Psychiatrist: All of life is difficult. But the moment she died, when we entered her house, it became very clear to me: she is back, as she once was. The person she once was, the pretty, intelligent girl with a heart of gold.

Artist: You remain a romantic, a religious fanatic. If you didn’t hold back, the Assumption of Mary would come now. You know that I have a hard time with so much transcendence. You are pretty much after our mother.

Psychiatrist: And after our father, you are more of a melancholic, always Janus-faced, one eye looking back, observing the present from the past.

Artist: The past is very important to me. All the many cardboard boxes in my mother’s house are filled with the past. Memories of three or four generations. Everything carefully organized and packed. Grandmother’s prayer book, mother’s golden curls that were cut off as a child and wrapped in a piece of paper, grandfather’s self-sewn national flag from 1945, our milk teeth and all the many photographs, right down to the photos of our daughter Anna. Our lives carefully collected as our mother’s inheritance. Is that what remains, the memories?

Psychiatrist: The memories and the wine. Do you remember the story about the wedding wine?

Artist: Pure horror. Typical mother. When we were 34, our mother bought the wedding wine for us on one of her tasting trips to France. A case of Chateau Phélan Ségur, Saint–Estéphe, vintage 1990. She spent 1000 francs on it. Without asking us. The wine box was moved with us for decades and was in all the cellars of the apartments where mother had lived. Not very good storage. No wonder that when the time finally came 16 years later and we got married, there was no more to be expected from this wine. But mother insisted that her wedding wine be served at the wedding. A couple of bottles were opened and it was worse than feared. Undrinkable. All the bottles had corks, some had mutated into a kind of port wine, or even vinegar.

Psychiatrist: But mother could not be convinced of that. She started an argument with those guests who did not want to drink the wine. For them, her wedding wine was delicious. Other guests who drank the wine out of ignorance or indifference were warned not to drink too much of it because the wine was so precious.

Artist: The wedding wine. After the wedding, we put the box with the last bottles that no one wanted to open because the wine was spoiled. back in the cellar. It is still there. Now, after her death, we wanted to honor Mother. We lit candles, put up photos of her and we took a bottle of wedding wine out of the box and opened it. Psychiatrist: And what a surprise! It was the best St. Emillion we have ever tasted. It was perhaps the only bottle that had not spoiled, but had matured over 30 years to become the best Burgundy. What an aroma, what a lovely scent. What a dignified, round taste! Artist: We were amazed. It was an enlightenment. The best wine last. Like in Canaan. Mother smiles at us again from heaven above: “Now you rascals see how right I was! The wine is heavenly!”

Psychiatrist: The main thing is that we still laugh! And she always laughed! That’s why we’re doing it in a really Catholic way today. Even though we’re quarter Jewish. We have already buried her father and we will lay our mother in the same grave. We will try to organize a mass and a good singer. And we will lay her in an open coffin. Can you think of anything else? Have we forgotten something?

Artist: No. We have said the most important thing. Let’s go and bury our funny mother.