The Grand Table

2016

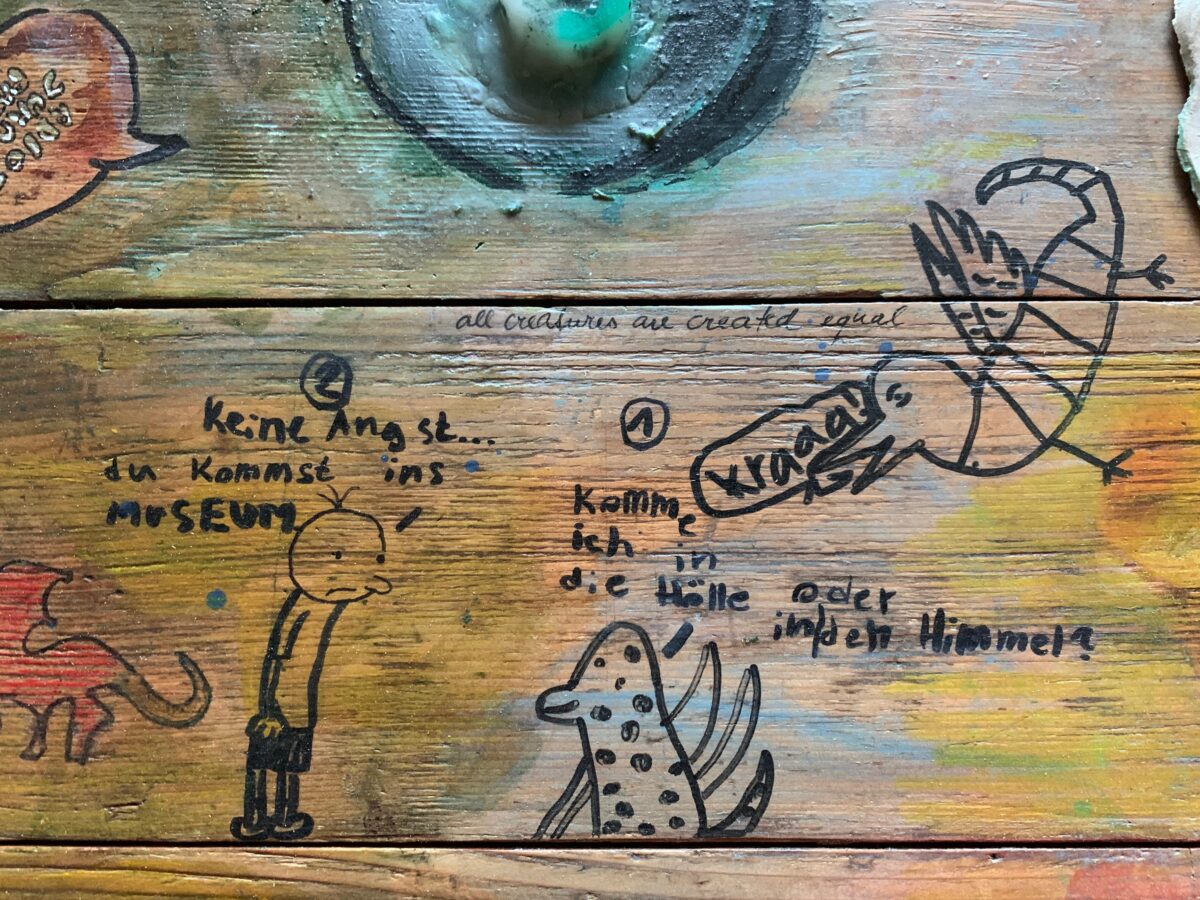

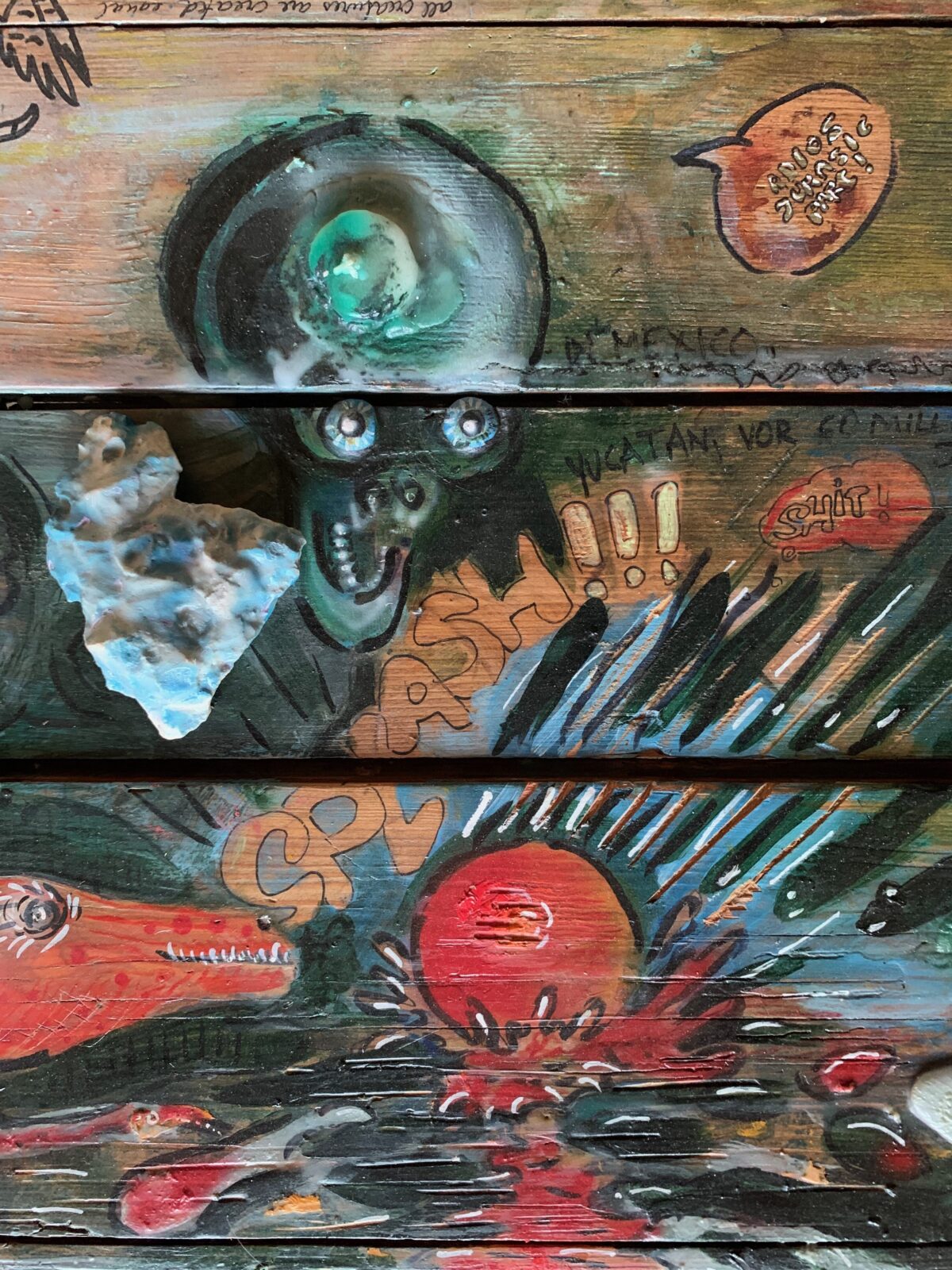

“When my daughter was small, we had a large dining table in our kitchen. I rescued the table from an old uninhabited house in Baden, just before it was demolished. It was a washstand made of long planks, smooth and worn from years of use. Anna’s high chair was at the head of the table. At some point Anna began to draw and write on the table. She also drew on the high chair, on the floor and on the bricks of the wall. I encouraged her to continue. Art knows no boundaries when it comes from the heart of a child, a madman or a good artist. Years before, I was lucky enough to be present at the filming of Heinz Bütler’s film “August Walla”. The Gugging patient and artist had to move out of his social housing in Klosterneuburg at that time and was moved to the “artists’ house” of the Gugging State Mental Hospital with his ninety-year-old mother, who was already suffering from dementia. I had admired August Walla for a long time. He was the prototype of an “art brut” artist. Like a child, Walla painted everyday objects around him: the table, the cupboards, the crate of a beloved hamster and the buckets in which he urinated. During filming, I learned that the Wallas’ former apartment was empty and that the whole house was soon to be demolished. I drove there and found myself in an abandoned wonderland. There was a table with “GOD” written on its legs in typical Walla script. A painted cupboard, written window sills, a painted door. Yes, that was it. Magic and reality, sorcery and madness, condensed into a “total work of art”. I dismantled the table and bar, the door and the window sills and packed everything into a car and rescued the fragments in Switzerland. It was not until many years later that I processed the intuitive, impulsive and sometimes magical actions of psychiatric hospital inmates. Encouraged by conversations and books by Harald Szeemann, Alfred Bader and Leo Navratil, I started the “Artists from Königsfelden” project at the Aargau Psychiatric Clinic Königsfelden in Windisch, which supported patients at the clinic in their artistic work. This explains why, many years later, I encouraged our four-year-old daughter to destroy the dining table. Years passed. Anna was no longer four, but eight or nine years old. The dining table was replaced. It was too narrow, just a laundry table – and like all that is no longer usable – it came into the studio. Anna began to ask questions. “How did God get to heaven?” “Why are there bad people?” “Do dead pictures also go to heaven?” Here began a journey that is not over yet. How does a father explain the world to his daughter? Anna and I looked for a way to talk about God and the world. The world was our old dining table. We started to draw together. To the left, where Anna once sat, was the beginning of the world, the Big Bang, the universe, the primordial soup, the dinosaurs. Every child goes through the dinosaur phase at some point. At the age of four or five, dinosaurs are part of the children’s room and the child’s fantasy world, and they take over from the teddy bear. Anna had a big dinosaur that she could even ride on. It moved, made pleasant noises, turned its head and opened its eyes. For a father interested in science, this was the best invitation to familiarize a child with the second law of thermodynamics, an expanding universe and the certain end of the world. For us, the table was a path, a place, a way and a work that began at Anna’s end of the table. We spoke and drew on the table. “Why are there no more dinosaurs?” Where do the unicorn live? How did gemstones come about? Do tooth decay even exist? Were you St. Nicholas last year? We worked on the table, on the boards that mean the world. Each of us on our own or on joint drawings and pictures. For years I have enjoyed working on pictures that I find in second-hand shops or bulky waste. Anna stuck her little stickers on the pictures and we worked on the existing picture material, either alternately or together. This is how “The Return of the Unicorn” came about. The overpainting of a reproduction of a flower painting by Renoir developed into an underwater landscape with corals, fish, small voracious monsters, worms and spiny animals (see also the chapter “Namoranna”).

The work on the grande table came to an end when our discussions on these topics came to an end. Anna grew bigger and the topics of our discussions changed. She didn’t want to hear anything more about the universe or the cursed second law of thermodynamics. So we ended the “big table” – the picturesque dialogue between daughter and father about the world, the universe and the dinosaurs, about life, love and death, which interrupts everything, destroys some things and completes others, so that something completely new can emerge again on the very left at the head of the grand table.”

- RB (December 2024)

“When my daughter was small, we had a large dining table in our kitchen. I rescued the table from an old uninhabited house in Baden, just before it was demolished. It was a washstand made of long planks, smooth and worn from years of use. Anna’s high chair was at the head of the table. At some point Anna began to draw and write on the table. She also drew on the high chair, on the floor and on the bricks of the wall. I encouraged her to continue. Art knows no boundaries when it comes from the heart of a child, a madman or a good artist. Years before, I was lucky enough to be present at the filming of Heinz Bütler’s film “August Walla”. The Gugging patient and artist had to move out of his social housing in Klosterneuburg at that time and was moved to the “artists’ house” of the Gugging State Mental Hospital with his ninety-year-old mother, who was already suffering from dementia. I had admired August Walla for a long time. He was the prototype of an “art brut” artist. Like a child, Walla painted everyday objects around him: the table, the cupboards, the crate of a beloved hamster and the buckets in which he urinated. During filming, I learned that the Wallas’ former apartment was empty and that the whole house was soon to be demolished. I drove there and found myself in an abandoned wonderland. There was a table with “GOD” written on its legs in typical Walla script. A painted cupboard, written window sills, a painted door. Yes, that was it. Magic and reality, sorcery and madness, condensed into a “total work of art”. I dismantled the table and bar, the door and the window sills and packed everything into a car and rescued the fragments in Switzerland. It was not until many years later that I processed the intuitive, impulsive and sometimes magical actions of psychiatric hospital inmates. Encouraged by conversations and books by Harald Szeemann, Alfred Bader and Leo Navratil, I started the “Artists from Königsfelden” project at the Aargau Psychiatric Clinic Königsfelden in Windisch, which supported patients at the clinic in their artistic work. This explains why, many years later, I encouraged our four-year-old daughter to destroy the dining table. Years passed. Anna was no longer four, but eight or nine years old. The dining table was replaced. It was too narrow, just a laundry table – and like all that is no longer usable – it came into the studio. Anna began to ask questions. “How did God get to heaven?” “Why are there bad people?” “Do dead pictures also go to heaven?” Here began a journey that is not over yet. How does a father explain the world to his daughter? Anna and I looked for a way to talk about God and the world. The world was our old dining table. We started to draw together. To the left, where Anna once sat, was the beginning of the world, the Big Bang, the universe, the primordial soup, the dinosaurs. Every child goes through the dinosaur phase at some point. At the age of four or five, dinosaurs are part of the children’s room and the child’s fantasy world, and they take over from the teddy bear. Anna had a big dinosaur that she could even ride on. It moved, made pleasant noises, turned its head and opened its eyes. For a father interested in science, this was the best invitation to familiarize a child with the second law of thermodynamics, an expanding universe and the certain end of the world. For us, the table was a path, a place, a way and a work that began at Anna’s end of the table. We spoke and drew on the table. “Why are there no more dinosaurs?” Where do the unicorn live? How did gemstones come about? Do tooth decay even exist? Were you St. Nicholas last year? We worked on the table, on the boards that mean the world. Each of us on our own or on joint drawings and pictures. For years I have enjoyed working on pictures that I find in second-hand shops or bulky waste. Anna stuck her little stickers on the pictures and we worked on the existing picture material, either alternately or together. This is how “The Return of the Unicorn” came about. The overpainting of a reproduction of a flower painting by Renoir developed into an underwater landscape with corals, fish, small voracious monsters, worms and spiny animals (see also the chapter “Namoranna”).

The work on the grande table came to an end when our discussions on these topics came to an end. Anna grew bigger and the topics of our discussions changed. She didn’t want to hear anything more about the universe or the cursed second law of thermodynamics. So we ended the “big table” – the picturesque dialogue between daughter and father about the world, the universe and the dinosaurs, about life, love and death, which interrupts everything, destroys some things and completes others, so that something completely new can emerge again on the very left at the head of the grand table.”

- RB (December 2024)