Art is a tumor—Ceci n’est pas une boule—La boulle est née, Le coup du sabre du roi

2007—8

The exhibition in the Kunstraum Aarau in 2008 summed up a long artistic journey of Roman Buxbaum. The starting point of the journey was a small ball that had started to grow on his right shoulder a few years earlier. As a former surgical assistant, Buxbaum knew lipomas well. Lipomas are benign, slowly growing fatty tissue tumors of the skin. They never degenerate and do not metastasize. If they are cosmetically disturbing, they are easy to remove. The surgeon cuts open the skin and peels the lipoma out with his finger – like peeling an orange.

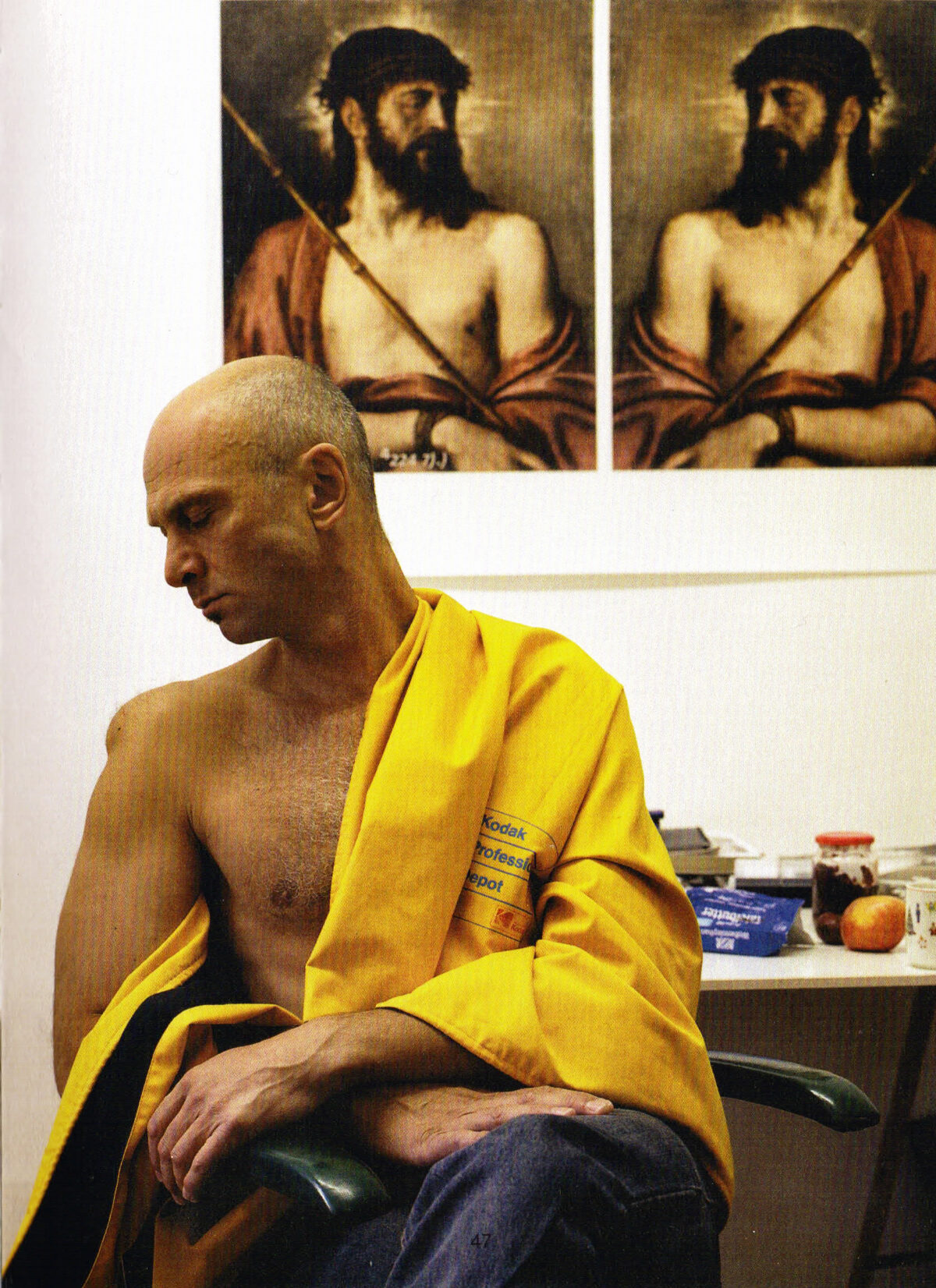

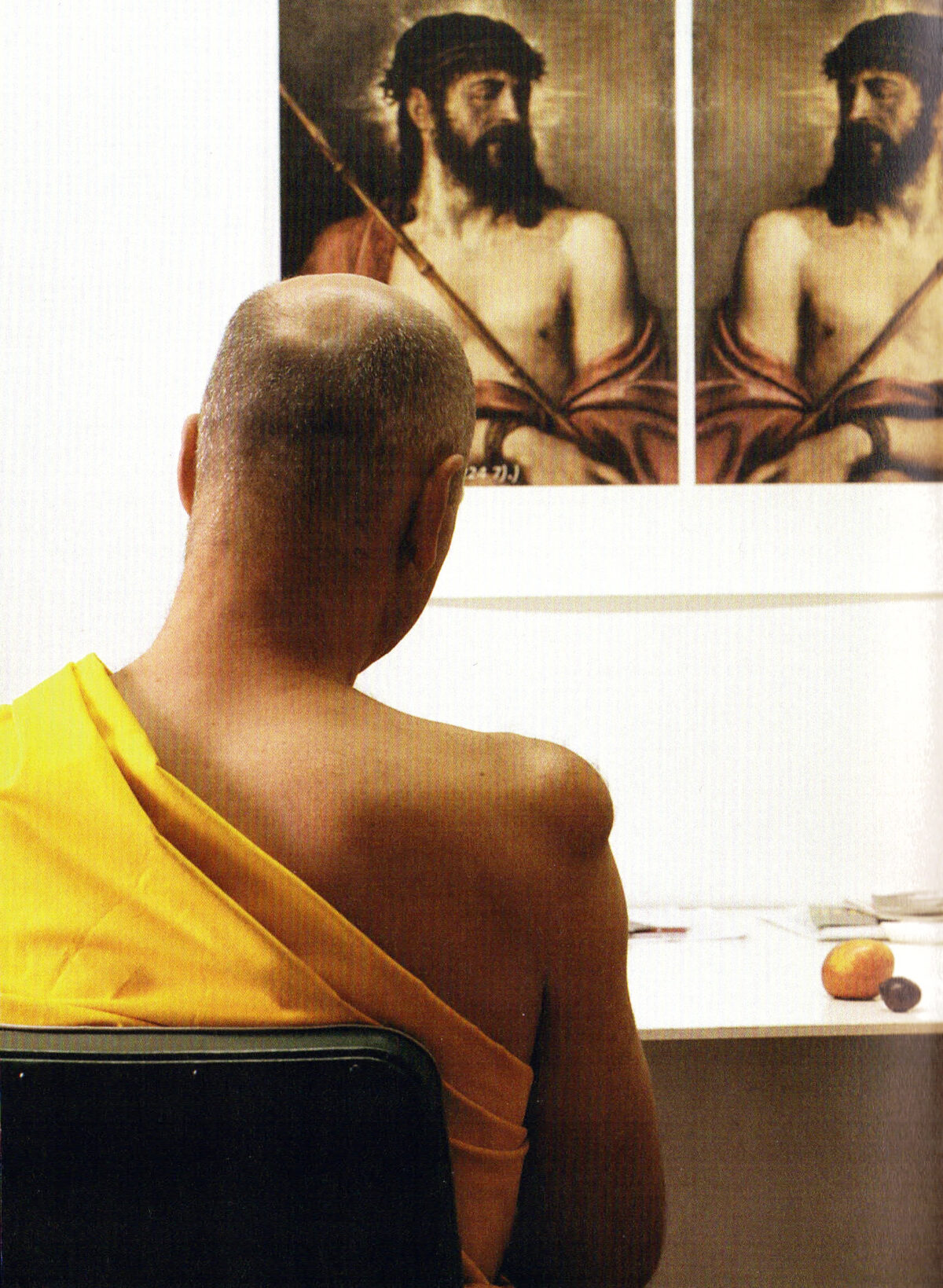

Buxbaum knew that his lipoma was harmless. It was in an unusual, easily visible place, on his right shoulder. He decided to let it grow. After about two years, it was the size of an orange. Art is illness! The artist’s body is the work. Since medical school, he has occasionally suffered from carcinophobic fears. Letting the lipoma grow on his shoulder was also a way of facing his fears of tumors – a self-treatment. Art is therapy.

In 1995 he gave a performance at the Nürtingen Art School entitled “Art is Illness”. He had his body examined by medical colleagues from different disciplines, dictating the findings and recording them on video. The medical view of one’s own body. The medical records were published. It replaced the usual artist biography and beginned like this: “The medical history begins on May 5, 1956 in the obstetrics department of the Podolí hospital in Prague. Roman Buxbaum was born after a pregnancy without complications in a simple, frontal cephalic position. The newborn’s height was within the normal range at 53 cm, as was his body weight at 2,800 g; no dysmorphia or deformities were found.”

As a psychiatrist, Buxbaum was also interested in the psychological connections between art and illness. Sigmund Freud suspected that the source of artistic energy was unconscious psychological conflicts. In two famous essays from 1908, Freud attempted a psychoanalytic interpretation of unconscious motives in a painting by Leonardo Da Vinci and the sculpture Moses by Michelangelo. Freud’s thesis was that artists, like neurotics, suppressed their libidinal drives. Neurotics produced symptoms and artists sublimated their libido into works of art. Buxbaum too decided to transform his hypochondria into art. The lipoma on his shoulder was no longer a tumor, it was now a work of art.

The lipoma had special sculptural qualities. At first it was a beautiful little ball. When it reached the size of an apple, increasing skin tension deformed it into an oval egg shape, an epaulette like those worn by women and generals. “Was it an award, or a small animal near my right ear that wanted to whisper something to me?” he asked himself.

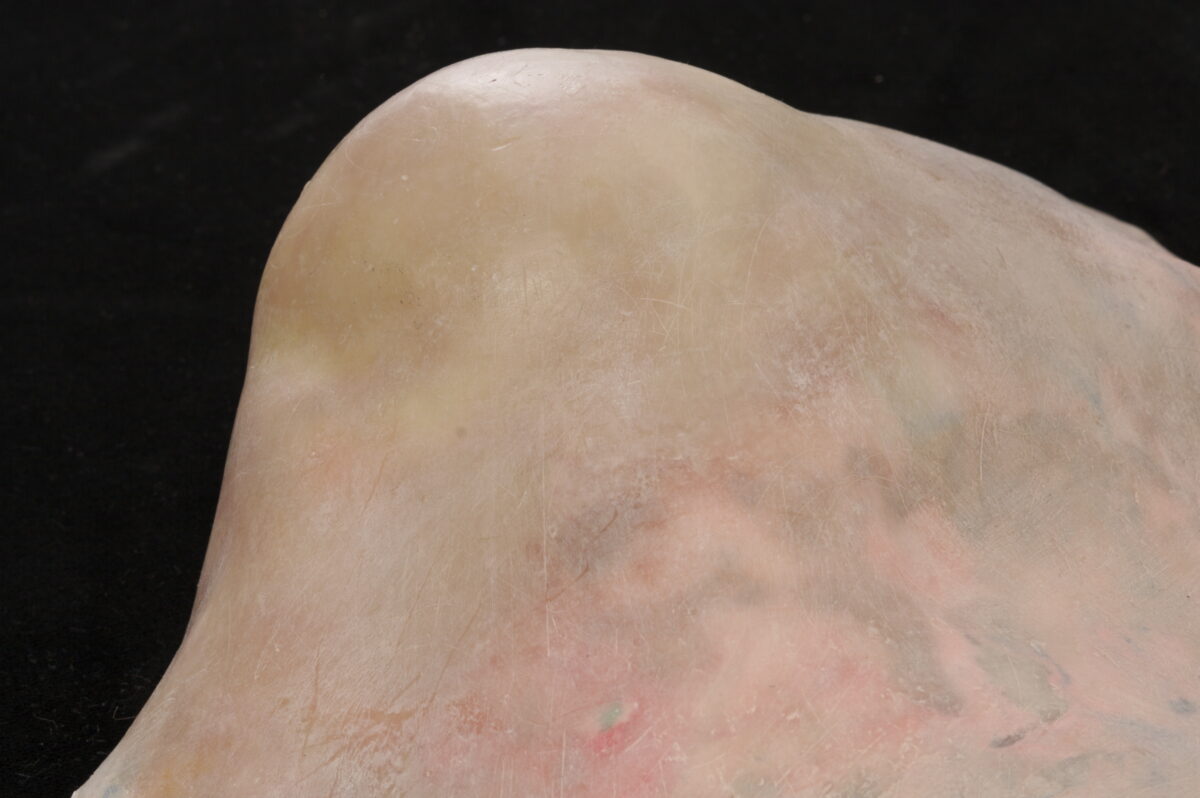

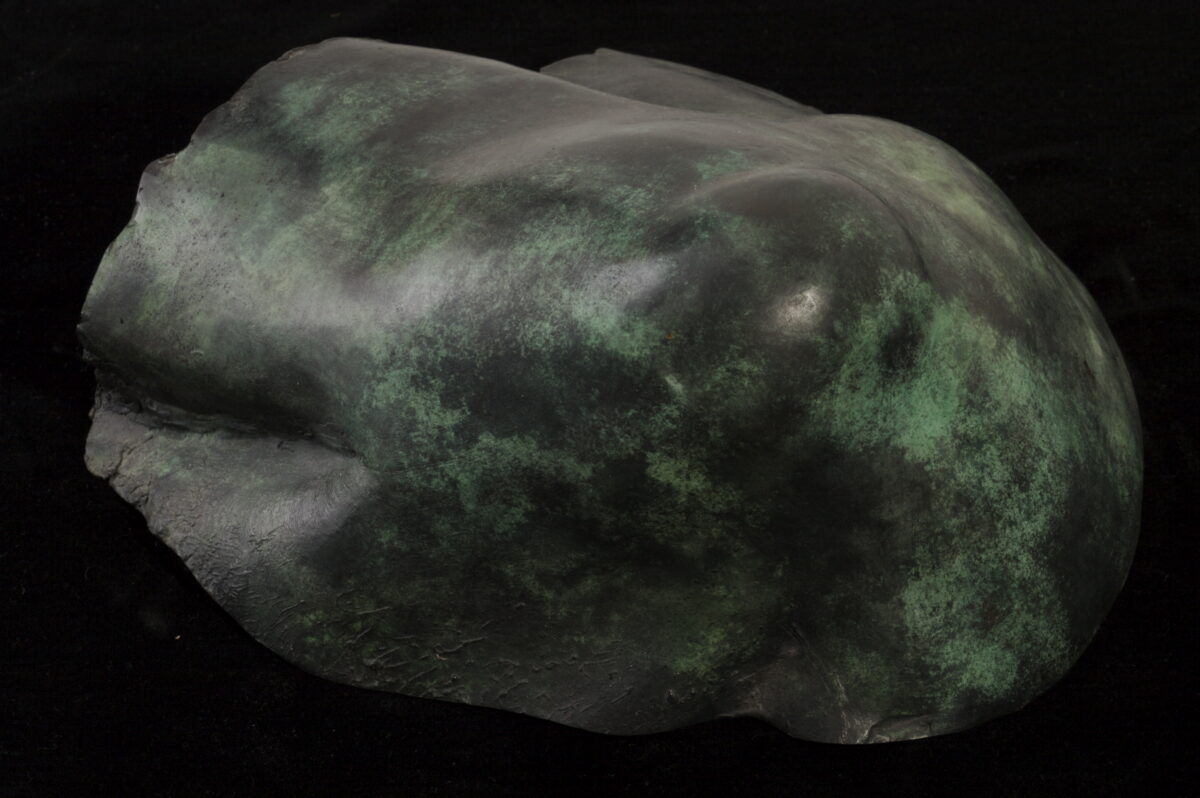

Inspired by Van Gogh and Egon Schiele, Buxbaum regularly drew self-portraits as a teenager, a practice he continues with to this day. His own body is an available model and the drawing of myself in front of the mirror is good practice for the day in the studio. I drew myself with my lipoma, photographed and filmed the strange hill that changed the landscape of my body. He casted the shoulder in plaster and clay. He learned the old technique of moulage and made exact replicas of his shoulder. Moulages are sculptures made of wax and painted, realistic replicas of skin diseases that were used for medical teaching at a time when there was no color photography. It is a fascinating and dying technique. In Switzerland there are only two specialists left who master it and restore the museum collections. As a medical student Buxbaum was fascinated by the moulage collection at the University Hospital of Zurich and learned some basic knowledge of the moulage technique from the then restorer Elisabeth Stoiber. I have now made several moulages of my shoulder. In addition to plaster casts, I also had bronzes of various sizes cast. Medicine has developed many new imaging techniques in recent decades. He applied the old imaging techniques to his “tumor”.

The next sculptural attempt was to be a bronze bust based on the model of the Roman emperors, with the dominant lipoma on the shoulder. The artist as a deformed person, but as a sick person in a narcissistically exaggerated pose. Unfortunately, Buxbaum and his collaborators encountered technical difficulties in making the plaster cast. The sculptor he commissioned to make his bust started with his back and the back of his head. Then the sculptor wanted to remove the face mask, then the arms and the chest individually from Buxbaum’s body in plaster molds. It never got that far. After the back mold had hardened, it became very uncomfortable. It could not be removed. The sculptor did smear his hair with it, but cemented the body hair and the hair on his head into the plaster. In addition, his right ear was in plaster and could not be removed. He was stuck in the plaster. Every attempt to remove the mold was extremely painful. The sculptor was a proven expert in plaster casts of ancient statues, but had never worked with a living, hairy body. Buxbaum ended up in the plaster room of the Brno hospital and had to be cut out of the plaster centimeter by centimeter by skilled nurses. The bust was never finished and he gave up the project.

Illness, cancer, and death usually leave people speechless. Fate leaves individuals speechless in shock, grief, and shame. Buxbaum wanted to develop this theme of speechlessness and the tragedy of fate into a drama between good and evil. The lipoma on his shoulder grew during the pregnancy of his daughter Anna. Ceci n’est pas une boule – La boule est née addressed the simultaneous growth of good and evil, of life and death. At the end of the 1990s, he began to transfer cross-media works from art spaces to theater stages. This resulted in audience-interactive performances such as My Art (Vienna Festival, Rudolfinum Prague), Of Dogs and Men (Theater Gessnerallee Zurich), and Buxbaum, Redlich, Hitler at the Theaterspektakel Zurich.

The first act was planned to be a theater performance in the Kunsthalle Rudolfinum in Prague. A surgeon was to operate on his lipoma in his shoulder. The performance was to take place as a shadow theater in the large foyer of the Rudolfinum. Video projections and the shadowy events of the tumor operation were to overlap on a semi-transparent curtain. The plot was simple: women give birth to children, artists give birth to art or tumors. Athena was born from Zeus’s thigh, and the tumor that was sitting on his shoulder was to be turned into a work of art through a Caesarean section. A simple theater. The main actors: the artist, his tumor, the surgeon, and an operating room nurse. The artist goes home, the tumor stays in the museum. Applause, curtain, lights out. Unfortunately, the plan never went ahead. The date was set and the invitation card was printed. He was already practicing the details of the performance with a team of lighting and sound technicians in a Prague theater. A few days before the performance, the devastating news came: the Medical Association of the Czech Republic had classified the public performance of the operation as unethical. The surgeon Dr. Josef Kalny and the operating assistant were forbidden to perform the lipomectomy in the Rudolfinum under threat of professional punishment. The performance fell through. If the surgeon was not allowed to come to the theater, the theater came to the surgeon. In a performance in Baden, Buxbaum made up for what was forbidden in Prague. His colleague Christian Roi cut the lipoma out of his shoulder with his katana — Le coup de sabre du Roi.

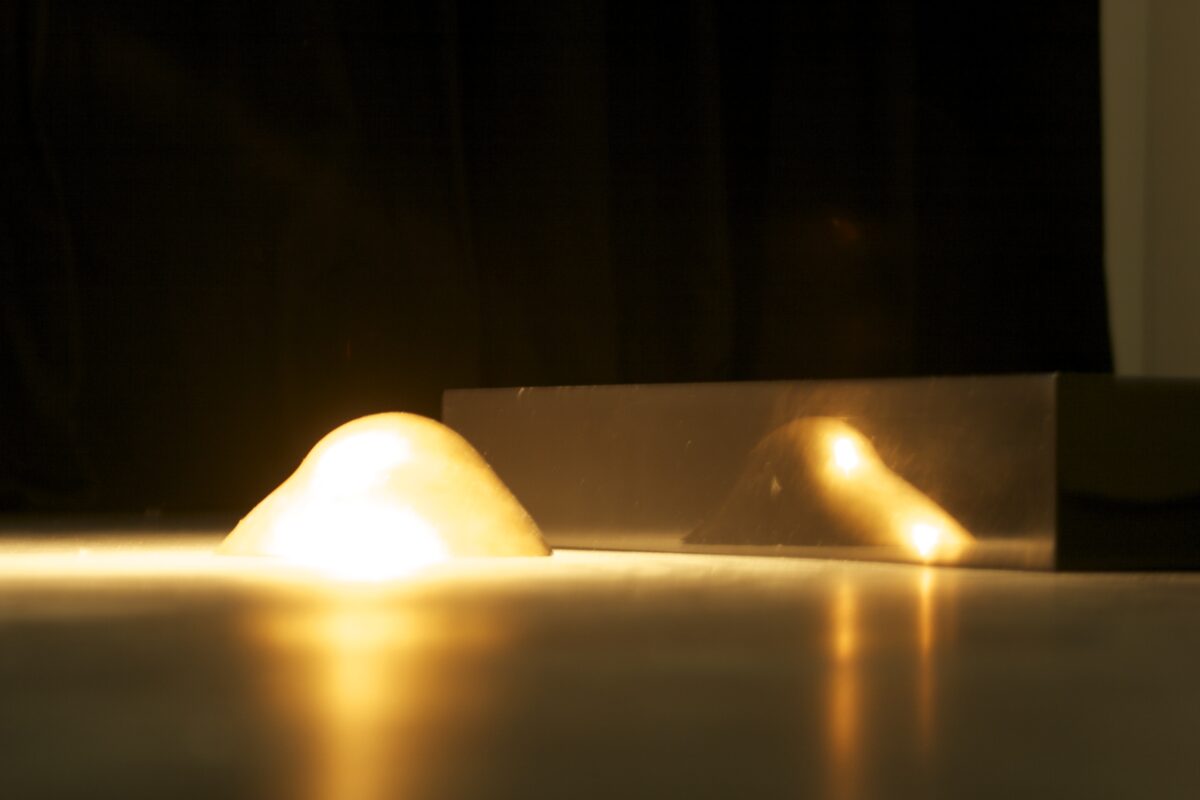

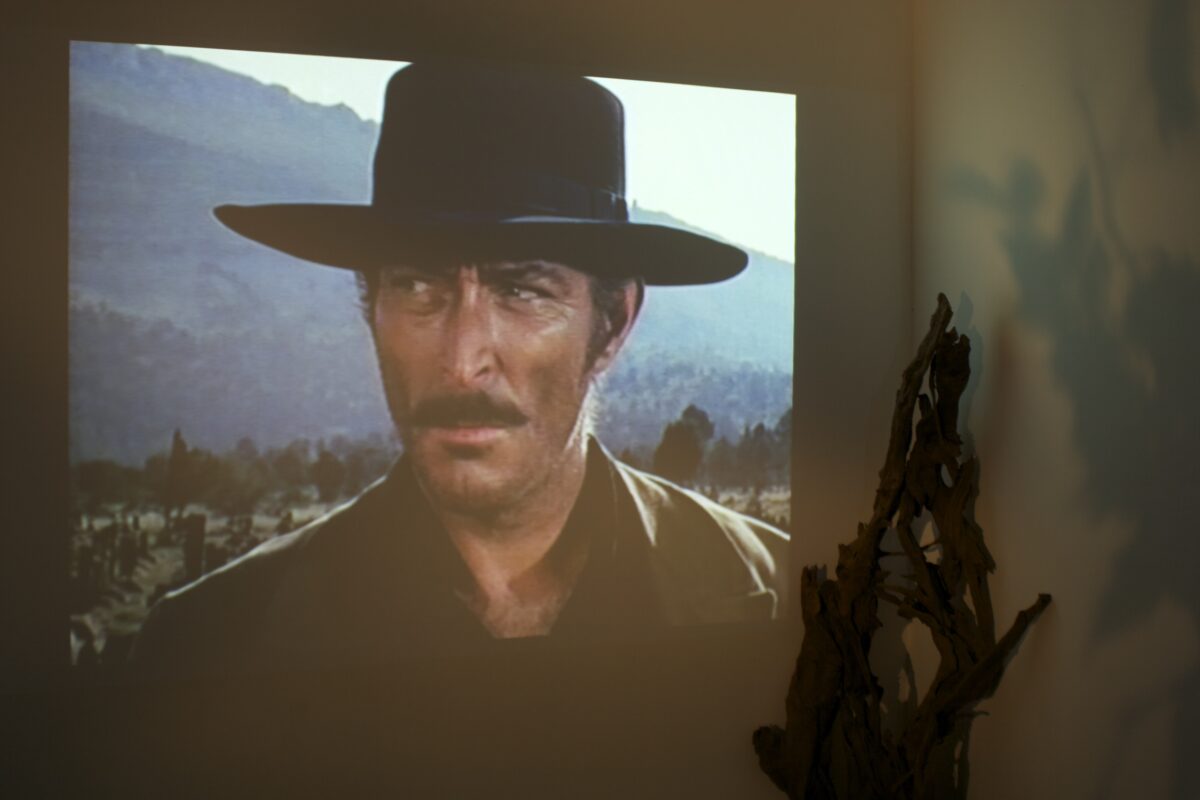

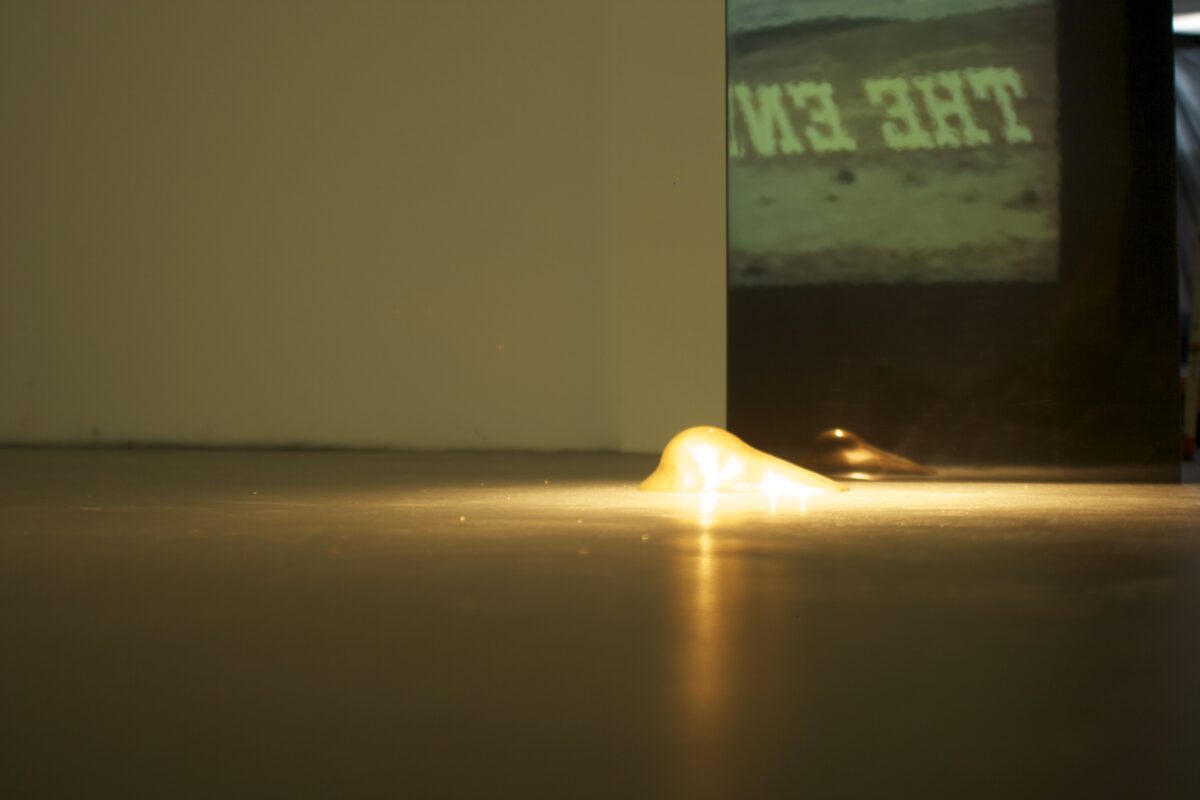

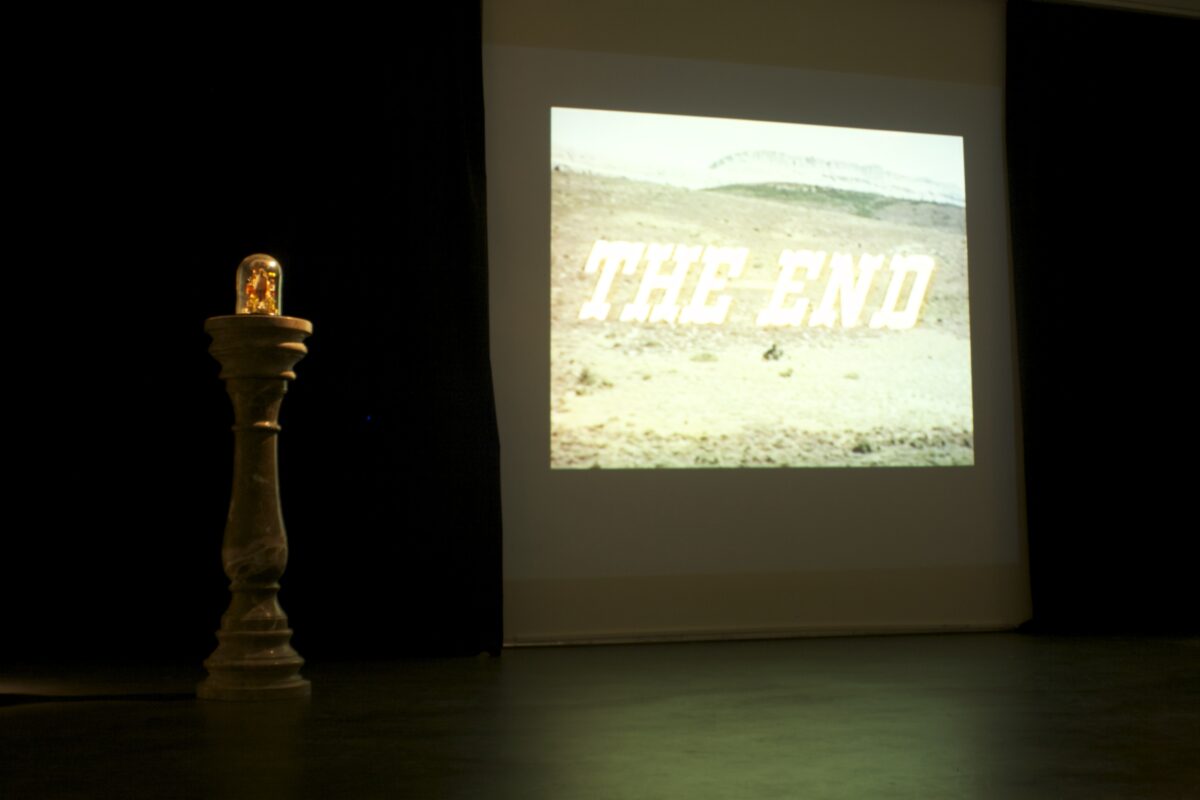

He realized the last act of the drama in the Kunstraum Aarau. In the darkened room, the bronzes, some highly polished, some darkened with verdigris, lay on the floor like small hills in a Mexican landscape. In between stood black steles, the surface of which was varnished with shellac and polished to a high gloss, so that they reflected the room like dark mirrors. The wooden steles had the dimensions of his body parts. The largest stele had the dimensions of body height × body width × depth. There was exactly enough room for him in the box in which it was transported — it could have been his coffin. In the darkened exhibition room, the black steles reflected the bronzes, which were illuminated with theatrical spotlights. The strict arrangement of the sculptures spatially referred to the central work of the exhibition — the tumor, which he had since had removed and placed in a kind of relic shrine. Under a bell-shaped glass dome, he fixed the lipoma on the remains of a baroque Calvary, where the cross with the figure of Jesus was missing. The tumor was the new Golgotha. He placed a photo of himself in front of the tumor. In his grandfather’s clothes, he looked like a convict. The gloomy staging in the Kunstraum Aarau was complemented by two video projections. They were cuts of the Spaghetti Western The Good, the Bad and the Ugly by Sergio Leone with the most wonderful soundtrack in film history by Ennio Morricone. One video projection showed the three protagonists of the Spaghetti Western in the decisive duel in the middle of a Mexican cemetery. Good (Clint Eastwood) triumphs over evil. A second video projection showed the last scene of the film. The hero gallops in a long shot from left to right across the screen into the next adventure until the scene with the iconic The End closes the film.

The exhibition in the Kunstraum Aarau (2008) marked the end of his tumor work, which revolved around the lipoma. He had no idea that in a few months he would be confronted with a real tumor. It was not clearly visible on his shoulder, but was hidden in his buttocks. After a bloody bowel movement, he became suspicious and felt the anal carcinoma with his index finger, as he had learned to do so often during rectal examinations of patients. He diagnosed a rough and hard lump about four centimeters in size on the lower, rear side of his anus, about three centimeters from the opening. The biopsy confirmed his bad feeling. It was a moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, which he found quite early enough. There were no metastases or offshoots in the lymph vessels. His carcinophobia (and the feeling finger) saved his life.

Looking back, he asked himself about the connection between the artistic approach to the subject and physical reality. Was the urge to deal with the lipoma on his shoulder the expression of his subconscious, which already had the real cancer on its radar? In other words: did art save his life?

The exhibition in the Kunstraum Aarau in 2008 summed up a long artistic journey of Roman Buxbaum. The starting point of the journey was a small ball that had started to grow on his right shoulder a few years earlier. As a former surgical assistant, Buxbaum knew lipomas well. Lipomas are benign, slowly growing fatty tissue tumors of the skin. They never degenerate and do not metastasize. If they are cosmetically disturbing, they are easy to remove. The surgeon cuts open the skin and peels the lipoma out with his finger – like peeling an orange.

Buxbaum knew that his lipoma was harmless. It was in an unusual, easily visible place, on his right shoulder. He decided to let it grow. After about two years, it was the size of an orange. Art is illness! The artist’s body is the work. Since medical school, he has occasionally suffered from carcinophobic fears. Letting the lipoma grow on his shoulder was also a way of facing his fears of tumors – a self-treatment. Art is therapy.

In 1995 he gave a performance at the Nürtingen Art School entitled “Art is Illness”. He had his body examined by medical colleagues from different disciplines, dictating the findings and recording them on video. The medical view of one’s own body. The medical records were published. It replaced the usual artist biography and beginned like this: “The medical history begins on May 5, 1956 in the obstetrics department of the Podolí hospital in Prague. Roman Buxbaum was born after a pregnancy without complications in a simple, frontal cephalic position. The newborn’s height was within the normal range at 53 cm, as was his body weight at 2,800 g; no dysmorphia or deformities were found.”

As a psychiatrist, Buxbaum was also interested in the psychological connections between art and illness. Sigmund Freud suspected that the source of artistic energy was unconscious psychological conflicts. In two famous essays from 1908, Freud attempted a psychoanalytic interpretation of unconscious motives in a painting by Leonardo Da Vinci and the sculpture Moses by Michelangelo. Freud’s thesis was that artists, like neurotics, suppressed their libidinal drives. Neurotics produced symptoms and artists sublimated their libido into works of art. Buxbaum too decided to transform his hypochondria into art. The lipoma on his shoulder was no longer a tumor, it was now a work of art.

The lipoma had special sculptural qualities. At first it was a beautiful little ball. When it reached the size of an apple, increasing skin tension deformed it into an oval egg shape, an epaulette like those worn by women and generals. “Was it an award, or a small animal near my right ear that wanted to whisper something to me?” he asked himself.

Inspired by Van Gogh and Egon Schiele, Buxbaum regularly drew self-portraits as a teenager, a practice he continues with to this day. His own body is an available model and the drawing of myself in front of the mirror is good practice for the day in the studio. I drew myself with my lipoma, photographed and filmed the strange hill that changed the landscape of my body. He casted the shoulder in plaster and clay. He learned the old technique of moulage and made exact replicas of his shoulder. Moulages are sculptures made of wax and painted, realistic replicas of skin diseases that were used for medical teaching at a time when there was no color photography. It is a fascinating and dying technique. In Switzerland there are only two specialists left who master it and restore the museum collections. As a medical student Buxbaum was fascinated by the moulage collection at the University Hospital of Zurich and learned some basic knowledge of the moulage technique from the then restorer Elisabeth Stoiber. I have now made several moulages of my shoulder. In addition to plaster casts, I also had bronzes of various sizes cast. Medicine has developed many new imaging techniques in recent decades. He applied the old imaging techniques to his “tumor”.

The next sculptural attempt was to be a bronze bust based on the model of the Roman emperors, with the dominant lipoma on the shoulder. The artist as a deformed person, but as a sick person in a narcissistically exaggerated pose. Unfortunately, Buxbaum and his collaborators encountered technical difficulties in making the plaster cast. The sculptor he commissioned to make his bust started with his back and the back of his head. Then the sculptor wanted to remove the face mask, then the arms and the chest individually from Buxbaum’s body in plaster molds. It never got that far. After the back mold had hardened, it became very uncomfortable. It could not be removed. The sculptor did smear his hair with it, but cemented the body hair and the hair on his head into the plaster. In addition, his right ear was in plaster and could not be removed. He was stuck in the plaster. Every attempt to remove the mold was extremely painful. The sculptor was a proven expert in plaster casts of ancient statues, but had never worked with a living, hairy body. Buxbaum ended up in the plaster room of the Brno hospital and had to be cut out of the plaster centimeter by centimeter by skilled nurses. The bust was never finished and he gave up the project.

Illness, cancer, and death usually leave people speechless. Fate leaves individuals speechless in shock, grief, and shame. Buxbaum wanted to develop this theme of speechlessness and the tragedy of fate into a drama between good and evil. The lipoma on his shoulder grew during the pregnancy of his daughter Anna. Ceci n’est pas une boule – La boule est née addressed the simultaneous growth of good and evil, of life and death. At the end of the 1990s, he began to transfer cross-media works from art spaces to theater stages. This resulted in audience-interactive performances such as My Art (Vienna Festival, Rudolfinum Prague), Of Dogs and Men (Theater Gessnerallee Zurich), and Buxbaum, Redlich, Hitler at the Theaterspektakel Zurich.

The first act was planned to be a theater performance in the Kunsthalle Rudolfinum in Prague. A surgeon was to operate on his lipoma in his shoulder. The performance was to take place as a shadow theater in the large foyer of the Rudolfinum. Video projections and the shadowy events of the tumor operation were to overlap on a semi-transparent curtain. The plot was simple: women give birth to children, artists give birth to art or tumors. Athena was born from Zeus’s thigh, and the tumor that was sitting on his shoulder was to be turned into a work of art through a Caesarean section. A simple theater. The main actors: the artist, his tumor, the surgeon, and an operating room nurse. The artist goes home, the tumor stays in the museum. Applause, curtain, lights out. Unfortunately, the plan never went ahead. The date was set and the invitation card was printed. He was already practicing the details of the performance with a team of lighting and sound technicians in a Prague theater. A few days before the performance, the devastating news came: the Medical Association of the Czech Republic had classified the public performance of the operation as unethical. The surgeon Dr. Josef Kalny and the operating assistant were forbidden to perform the lipomectomy in the Rudolfinum under threat of professional punishment. The performance fell through. If the surgeon was not allowed to come to the theater, the theater came to the surgeon. In a performance in Baden, Buxbaum made up for what was forbidden in Prague. His colleague Christian Roi cut the lipoma out of his shoulder with his katana — Le coup de sabre du Roi.

He realized the last act of the drama in the Kunstraum Aarau. In the darkened room, the bronzes, some highly polished, some darkened with verdigris, lay on the floor like small hills in a Mexican landscape. In between stood black steles, the surface of which was varnished with shellac and polished to a high gloss, so that they reflected the room like dark mirrors. The wooden steles had the dimensions of his body parts. The largest stele had the dimensions of body height × body width × depth. There was exactly enough room for him in the box in which it was transported — it could have been his coffin. In the darkened exhibition room, the black steles reflected the bronzes, which were illuminated with theatrical spotlights. The strict arrangement of the sculptures spatially referred to the central work of the exhibition — the tumor, which he had since had removed and placed in a kind of relic shrine. Under a bell-shaped glass dome, he fixed the lipoma on the remains of a baroque Calvary, where the cross with the figure of Jesus was missing. The tumor was the new Golgotha. He placed a photo of himself in front of the tumor. In his grandfather’s clothes, he looked like a convict. The gloomy staging in the Kunstraum Aarau was complemented by two video projections. They were cuts of the Spaghetti Western The Good, the Bad and the Ugly by Sergio Leone with the most wonderful soundtrack in film history by Ennio Morricone. One video projection showed the three protagonists of the Spaghetti Western in the decisive duel in the middle of a Mexican cemetery. Good (Clint Eastwood) triumphs over evil. A second video projection showed the last scene of the film. The hero gallops in a long shot from left to right across the screen into the next adventure until the scene with the iconic The End closes the film.

The exhibition in the Kunstraum Aarau (2008) marked the end of his tumor work, which revolved around the lipoma. He had no idea that in a few months he would be confronted with a real tumor. It was not clearly visible on his shoulder, but was hidden in his buttocks. After a bloody bowel movement, he became suspicious and felt the anal carcinoma with his index finger, as he had learned to do so often during rectal examinations of patients. He diagnosed a rough and hard lump about four centimeters in size on the lower, rear side of his anus, about three centimeters from the opening. The biopsy confirmed his bad feeling. It was a moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, which he found quite early enough. There were no metastases or offshoots in the lymph vessels. His carcinophobia (and the feeling finger) saved his life.

Looking back, he asked himself about the connection between the artistic approach to the subject and physical reality. Was the urge to deal with the lipoma on his shoulder the expression of his subconscious, which already had the real cancer on its radar? In other words: did art save his life?